EMILY WHITCHURCH analyses notions of performance in Florence + The Machine’s Dance Fever album and tour.

Florence and the Machine’s latest album, Dance Fever, is a vehicle for catharsis and introspective ‘analysis of performance’. It takes its name from the dancing plague that swept through medieval Europe as masses of people danced themselves to exhaustion, or death. While Florence Welch began writing the album pre-COVID, it became crucial for Dance Fever to ‘give people a world to escape into’ as the pandemic sparked a global wave of anxiety, grief and isolation.

Throughout Dance Fever, Welch adopts various personas – king, medieval choremaniac, Trojan princess – as vessels for self-reflection: ‘How I make sense of the world is to turn it into myth and fable. Turning people and things into characters’, she explains. From music video co-starring Bill Nighy as her personified anxiety, to theatrical live choreography, Welch is a well-versed role-player.

Perhaps the most overt act of impersonation occurs in ‘King’, the album’s opening track and a pensive ode to the pulls of domesticity: ‘I am no mother, I am no bride, I am king’. With her ‘golden crown of sorrow’ and ‘bloody sword’, Welch grapples with her identity as a performer and her potential as a mother. After a cathartic yet melodic scream, the closing lyrics encapsulate Welch’s seemingly inextricable ties to the act of performance: ‘I was never as good as I always thought I was / But I knew how to dress it up / I was never satisfied, it never let me go / Just dragged me by my hair and back on with the show’.

Similar ideas are explored in the theatrical ‘Heaven is Here’. Following its Gregorian-style chanting and clapping, the song closes with spoken word: ‘And every song I wrote became an escape rope / Tied around my neck to pull me up to Heaven’. Here, music appears to be both restrictive and liberating – she may be consumed by songwriting, but performance ultimately carries her to the joys of heaven.

For Welch, performance also allows for honesty – ‘All the things that I ran from / I now bring as close to me as I can’, she sings in ‘Prayer Factory’. She describes these ‘things’ as her ‘shining trinkets of grief’, creating a level of ambiguity by suggesting a sense of self-acceptance, forgiveness even, or perhaps a longing for the familiar comfort of sadness and grief. The final track on the album, ‘Morning Elvis’, is equally poignant: ‘And if I make it to the stage, I’ll show you what it means to be spared’, she confesses, reflecting on a drunken trip to Memphis. Performance, for Welch, is a testament to her survival.

Dance Fever ultimately became a product of the pandemic, plunging us into a world where performancewasn’t possible. ‘I don’t know where to put my love’, she admits, struggling with the inability to perform against upbeat synth in ‘My Love’. Similarly, in ‘Cassandra’, Welch embodies the Trojan princess blessed with the ability to see the future, but cursed to never be believed. Mourning the loss of performance and the collective experience that came with it, her ‘empires’ and ‘cathedrals’ of connection crumbled.

‘My whole career, I really only had live goals. I didn’t think about No. 1 records or singles’. With roots in South London’s live music scene, Welch’s music feels undeniably designed for live performance. The Dance Fever tour was a creative, emotive triumph, a ‘resurrection of dance’ after such intense isolation.

Describing her stage persona as a mix between ‘Rogue from “X-Men” and a Victorian ghost’ feels acutely accurate – she is fiercely agile, sprinting around arenas and throwing herself into the crowd, but also delicate, taking moments to be softer. Fans did not hesitate to dive headfirst into Welch’s thespian realm; extravagant outfits, makeup and accessories became a much-loved fixture of every show on the tour, all of which was meticulously documented on Instagram.

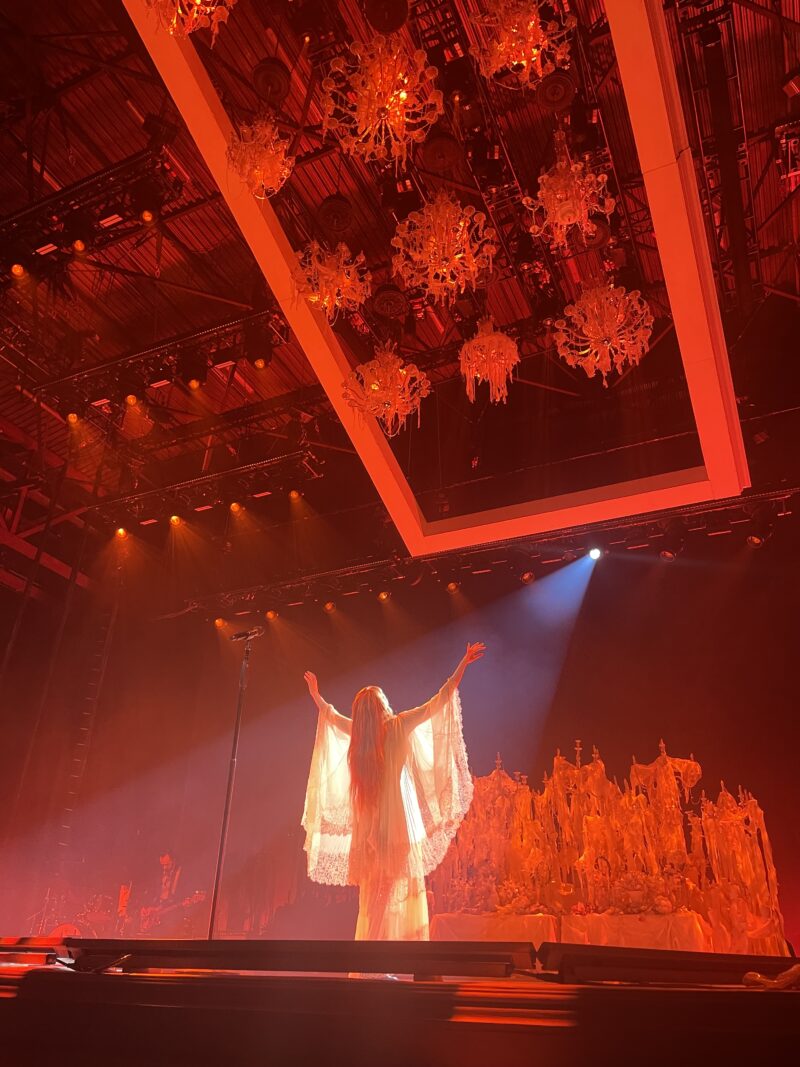

Watching her for the seventh time on the tour’s closing night in Spain, I feel well-accustomed to the show’s rituals: a shrine of flower crowns and trinkets at the back of the stage, chandeliers dripping with lace echoing the bedraggled beauty of Dickens’ Miss Havisham. Welch is, after all, the ‘architect of [her] creativity’. ‘Restraint’ is delivered as though she is possessed by some otherworldly force, with sudden, dramatic movements choreographed against choral gasps – a testament to the ‘bodily’ performances through which Welch exorcises her rage.

Yet, performance is not restricted to the stage. Welch’s interactions with front-row fans feel truly transcendental, shattering both the physical and psychological barrier between artist and fan. ‘Dream Girl Evil’ is laden with ferocity and satire, condemning the double standards imposed on women, especially as artists. ‘I am nobody’s moral centre’, she belts from atop the barrier, clutching our hands. Gender performance also comes into play here, echoing themes from ‘King’ – ‘But a woman is a changeling / always shifting shape’ – as she is confronted with the unattainable expectations placed on her by men.

Performance is ultimately a tool for Welch to convey real, raw emotions; to, as she recognises in ‘Free’, ‘exist in the face of suffering and death and somehow still keep singing’.

Featured image courtesy of Emily Whitchurch