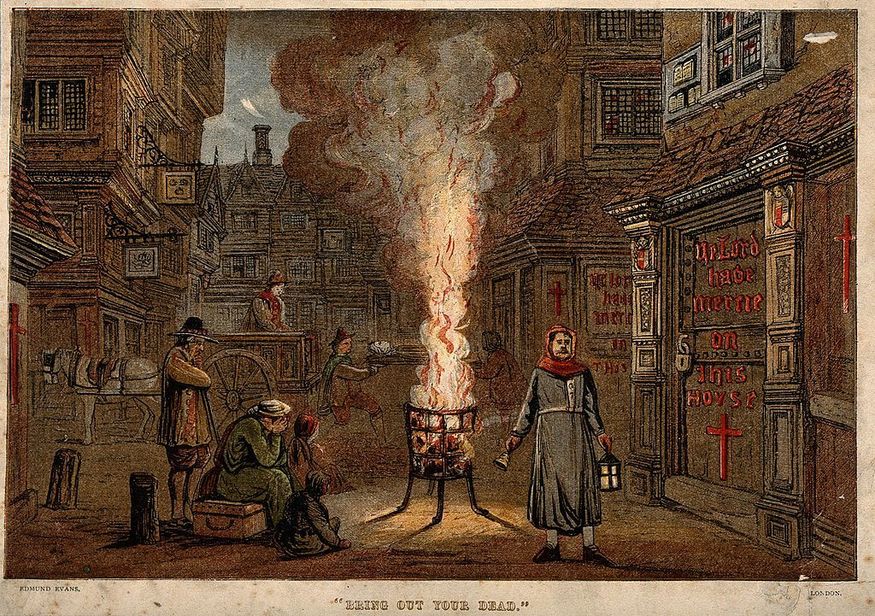

CRESSIDA O’KELLY draws a parallel between Defoe’s account of London’s ‘Great Plague’ and today’s Covid-19 pandemic.

Daniel Defoe was an eighteenth-century journalist, political polemicist and spy. His ideological vacillations once made him the perfect man to capture the destruction of London by a shapeshifting, unintelligible plague. A few hundred years later, we know a lot more about our current biological enemy, coronavirus, than Defoe ever knew of his, but the sentiment in A Journal of a Plague Year rings strikingly true for a populace once again besieged by disease.

Defoe explicitly planned for his Journal to be of use to future sufferers of epidemics in the capital. A Journal of a Plague Year was written retrospectively about the plague of 1665 and purports to be an accurate eyewitness account. Nevertheless, as Defoe was only five years old at the time of the ‘great visitation’, his attempts at historical accuracy are subverted by the fictional perspective of the narrator, referred to only as ‘ H.F’. Despite this, H.F. professes an aim to inform and instruct; ‘I have set this particular down so fully, because I know not but it may be of Moment to those who come after me’, and three hundred years later, as predicted, we return to his pages. Defoe’s anecdotes of infection, grief and survival make for strangely cathartic reading – if only to put the current mortality rate into perspective. Horrifically, in 1665 a quarter of the population of London died from the Great Plague.

An overriding anxiety in A Journal of the Plague Year is the spread of misinformation which, in a decade infested with ‘fake news’, the twenty-first-century citizen of London is sure to sympathize with. H.F. reminisces about the good old days before print news, when the veracity of information could truly be relied upon. I hate to think what he’d make of our digitalised information age.

We had no such thing as printed News Papers in those Days, to spread Rumours and Reports of Things; and to improve them by the Invention of Men, as I have liv’d to see practis’d since. But such things as these were gather’d from the Letters of Merchants… and from them was handed about by Word of Mouth only; so that things did not spread instantly over the whole Nation, as they do now.

H.F. foregrounds an unease about the ability of ‘Rumours’ to be aggrandised by ‘the innovation of men’, which mirrors the disquiet in our modern capital about sensationalised coronavirus headlines. Without naming names, some newspapers and social media outlets have distributed information designed to shock and confound, rather than to inform, contributing to rising rates of xenophobia and damaging conspiracy theories.

Indeed, to Cynthia Wall writing in The Rebuilding of London, Defoe’s rebuke of ‘News Papers’ contains an apprehension about the modernisation of London. A Journal of a Plague Year is set one year before the Great Fire of 1666 and, to Wall, ‘the spatial desolation to come haunts the streets of this text’. The amalgamation of fiction and non-fiction elements in the narrative signify the creation of a new literature for a newly rebuilt London. Wall remarks that in the Journal, as well as Defoe’s other urban novels, the author ‘responds directly, and with generic innovation, to the changed boundaries and significances of London’s urban spaces’.

The transmission of information thus becomes a double infection, running parallel to the contagion of the plague. With a retrospective understanding of epidemics, news ‘handed about by word of mouth’ is a contact site for the distemper to spread between individuals, a jumble of body parts amalgamated into the ultimate germ-fest.

In a perverse way, London is united through contagion. Today, we’re all sick with Covid (well, around one in 15 of us anyway). The implications for mental health caused by rampant infection were remarked upon even in Defoe’s day. H.F. describes a London of ubiquitous despair; it seems almost architecturally composed of sadness:

The Face of London was now indeed strangely alter’d, mean the whole Mass of Buildings, City, Liberties, Suburbs… the whole, the Face of Things, I say, was much alter’d; Sorrow and Sadness sat upon every Face; and tho’ some Part were not yet overwhelm’d, yet all look’d deeply concern’d.

Much like today, the collective facial expressions of Defoe’s Londoners are consolidated into a homogenous frown. The ‘Mass’ of furrowed buildings creates an intense claustrophobia to the Journal while the setting of tangled streets forces once heterogeneous habitation into coexistence. This unity contrasts starkly with the usual characterisation of London as constantly fluid, diverse and impossible to capture between pages. Perhaps then, our sudden allyship presents an opportunity. We may rely on each other, even over a distance of three hundred years; a partnership of hopeful survivors in a city beset by plague.

Featured image source: i.guim.co.uk