ALEXANDER BURGANOV interviews Pussy Riot’s NIKA NIKULSHINA.

This interview is a transcript from ‘Russian Protest Art in the Context of the Political Spectrum’, an online event held by UCL’s History of Art Society on 20th January 2021.

Pussy Riot’s Nika Nikulshina is an artist and activist. Her most notable performances include: Policeman Enters the Game (2018), in which Nikulshina invaded the football field during the FIFA World Cup final match with a group of friends dressed in police uniform; 2036 (2020) on Moscow’s Red Square, a critical commentary on amendments to the constitution and the extension of the current Russian president’s term; and an untitled performance in 2020 in which the artist placed LGBTQ+ symbols on the buildings of the FSB (Russia’s Federal Security Service). Nikulshina has consequently been arrested for her artistic actions on numerous occasions.

Here, Nikulshina is interviewed by Alexander Burganov. Burganov is an independent curator, art historian and lecturer at Lomonosov Moscow State University. Burganov’s research focuses on Russian contemporary, underground and protest art. He is also the founder of the underground art gallery, Za Shkoloy, meaning ‘behind the school.’

А. B: To start with, when did you first encounter protest performance art and decide to pursue it?

N: As someone who has spent almost my entire life in Putin’s Russia, I have always had an understanding that everything that happens within the Russian political system is wrong. However, this frustration reached a certain point and I just didn’t know what I could do; I didn’t feel strong enough to translate my indignation into an artistic gesture.

The turning point for me was the 21st FIFA World Cup, held in Russia from 14 June to 15 July 2018, when Moscow was made into such an absolute showcase arena for foreign citizens to come and see how good everything is here, when in reality, it is very bad. I remember the moment when I decided to take part in Policeman Enters the Game and started developing the performance alongside Petya Verzilov. This moment came after one of the previous matches; people were dancing in the street. It was really beautiful and fun, there was this sense of unity. But then a police car broke into the crowd of dancing people and started to suppress them in a very rude way, and then to detain them. It was very upsetting that, for some reason, this celebration of life was a showcase for foreigners, but was absolutely not a celebration for people who live in Russia.

This police incident therefore generated the artistic imagery that we then transposed into our actionist gesture. Indeed, in our performance, there was some kind of game going on, some kind of happiness, some kind of life, then a policeman burst in and broke up the game. That was the beginning, and after that, I somehow stopped separating my life and my art, because I realised that the artistic expression of my thoughts is a big part of me. And that’s why when something happens in Russian politics or in Russian society that I find difficult to live with, I speak out about it. This is how my journey as an artist began.

А. B: Let’s focus on this connection you make between life and art. In your opinion, what is art in the 21st century? I’ll name four different artists. Let’s say for instance: Pyotr Pavlensky, who mainly creates political performance art; Yayoi Kusama, who utilises performance but also installations, paintings and so on; David Hockney, who mainly paints; and Zurab Tsereteli, who is a very academic artist, working in sculpture and painting. That’s the gradation. Their practices are vastly different, but it is common to categorise it all under one word: art. Why is there such a wide spectrum, and how do you define what art is today for yourself?

N: Listen, I want to make this clear right away: we can talk about contemporary art, we can talk about art more broadly. And when we talk about art more broadly, it seems to me that it is not very important whether it is from the 21st or the 20th century, or whenever. For me personally, art in itself always has to do with overcoming some kind of boundary. The thing that makes art art is some kind of edge, some kind of transcendent transition. Each time period certainly has its own traits, but for a gesture to become art, there has to be work with some ‘overcoming of boundaries’.

For me, therefore, to use the example of Tsereteli, he stops being an artist when he starts working to please the interests of the state. If you reproduce some kind of state agenda, in my opinion, you cease to be an artist. You become an ‘aesthetically-political performance’ to please Russian politician Yuri Luzhkov. I would not classify his work as art, it is just some kind of hobby or craft.

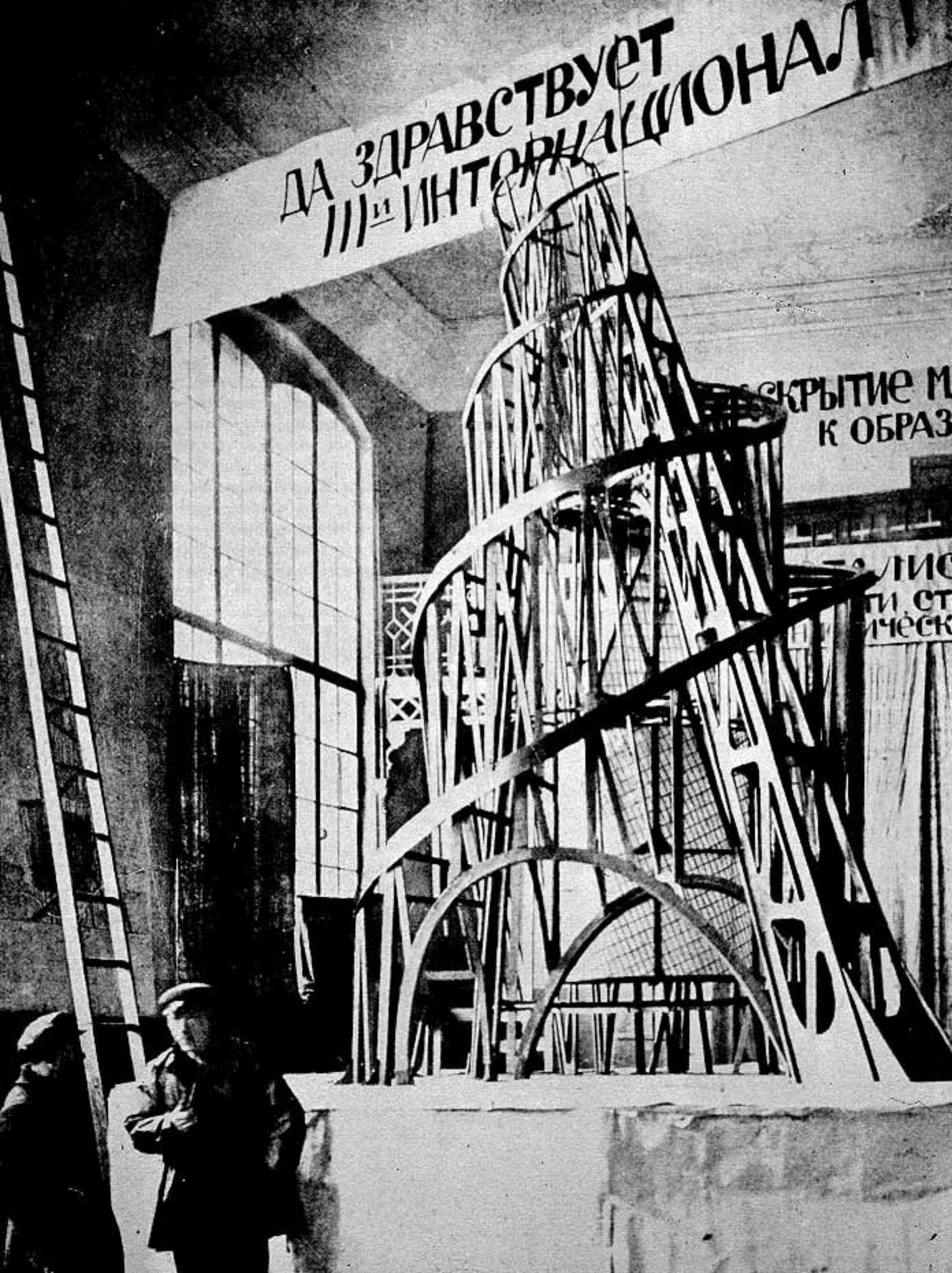

А. B: Well then, what about, say, David Hockney’s stained glass windows in honour of the British Queen [stained glass window in Westminster Abbey commemorating the anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s reign, 2018]? That is considered art, but is associated with the current government. That’s just half of it, what about Tatlin and his tower [Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, 1919], made during the Bolshevik period and another complete symbiosis between the artist and the current government?

N: It is important to separate the Bolsheviks, the aesthetics of the Russian Avant-Garde, and our current contemporary moment in Russia in one’s mind. Because at some point, the fusion of the Soviet power and the artists was productive. It facilitated new forms in art, it manifested socialist realism, it served the purpose of art. Then something went wrong, and once again art turned into a craft to please the state. That period of time you’re talking about, it was certainly full of great artists who made art.

А. B: OK, you answered about Tatlin. And David Hockney?

N: I have a really unpopular position here, but I really don’t think it is art. I don’t really have an exact answer because we still live within the paradigm that an artist’s persona extends into everything they do, meaning the question of celebrity clouds one’s judgement here. And there is no getting away from that. If a famous artist makes any gesture, that gesture becomes a work of art, simply by the fact that contextually it works. Although, I guess when Hockney does stained glass for utilitarian purposes, like that gesture you mentioned, I’d probably think of it as a craft too. The two binary oppositions are really colliding here, I’m probably contradicting myself. But if you take the gesture as a pure gesture, I wouldn’t classify it as art.

А. B: Alright, let’s say art is forcing the limits and a gesture is inextricably linked to the artist’s personality. In that case, who can we think of as an artist-activist, and where does the line between political activism and art activism lie? For instance, the Palace Coup by the art group Voina [‘War’] (2010), or Flags, Pussy Riot’s birthday greetings to Putin (2020) – why are these art and not just political manifestos?

N: I guess we have to go back to what determines art for me there, and that is again overcoming some boundary and interacting with layers within which it is supposedly impossible to interact. When we talk about the Palace Coup by Voina, for example, everything makes sense here: it makes sense that this action was taken at precisely the moment that it was (such an action could have happened now, but with the different consequences), so there is some kind of boundary-crossing there. The same could be said for the ‘Putin’s birthday’ example you gave. If we took the flag action to a European country where LGBTQ+ symbolism is acceptable, this gesture ceases to be an act of actionism, because it does not work against any of the layers that need to be overcome. But in the context of Russian reality, it is an art action.

Art works with images. When we’re talking about a rally, it’s a political action. When we talk about a monstration [Monstration is a mass artistic action in the form of a demonstration with slogans and banners], then we can talk about it as an art action, because the protestors work within some kind of figurative, sensual range that has nothing to do with mundane reality or with the utilitarian, but that influences and somehow changes this reality.

А. B: And if we talk about the art community, art critics, artists, and so on, not in the broad sense of the word, but specifically in relation to art-actionism, do protest artists and activists in Russia form some kind of unified community, or are they separate, non-intersecting figures and small groups? How well do you know other action artists apart from Pussy Riot? Do you socialise? Does this constitute a discourse, a discursive field, or is it a series of initiatives not connected into a unified community?

N: No, unfortunately, we have not brought the community feel of Russian art movements such as Moscow Conceptualism to the present day, when there was such a cohesive group whose art was born out of endlessly committed discourse. In the present moment, basically all artists are individualists. Yes, we all meet up at some parties, but we don’t communicate during the working process.

А. B: Following group performances in which a certain number of people take part, we as the audience don’t always even know the names of all the participants. Not all of the participants position themselves as artists, not all of them appear in the media space as artists. Even in relation to the first Pussy Riot line-up, many of the names of the participants are still unknown to the audience. How does this ranking of status take place within the collective that creates the action? Who can we think of as the author? As the artist? A volunteer? Does any involvement with an action make a person an artist?

N: This is such an important question that you have to decide for yourself. If you want your name to be inscribed in the art, then work on your personal brand. Say if, in a given action, I include myself in a collective called Pussy Riot, then within the context of a given artistic event I share the group’s ideas; I share the group’s manifesto, and together we create some sort of a product, within which the hierarchy of ‘author-client-publisher’ is rather insignificant.

А. B: How many people in total have performed as part of Pussy Riot throughout the history of its existence?

N: The thing is that we are not a party with party tickets and membership fees. No one is counting. In that way, the existence of the event itself is more important here than counting the participants. I’m afraid I couldn’t answer this.

А. B: But in terms of artists known to the public, we know very few names. Definitely fewer than there were participants.

N: It has to do with how one thinks about oneself in general. Some people who took part in the actions did not think of themselves as artists, they thought of themselves as political activists. So, they were part of some performance, but they didn’t want to make any new artistic structures out of themselves. Accordingly, they will be less well-known because they don’t want to move on within an artistic discourse.

А. B: That was not a random question, it has to do with the topic I would like to discuss further. I’ll start with an explanation, because I think part of the English-speaking audience may not be aware of what I want to ask. In Russia, there is such a thing as the National Bolshevik Party (NBP), a political party that was founded by artists Letov, Kuryokhin, Limonov and Dugin in 1993. On one hand, this party was created to represent a mixture of left and right-wing political views, but most importantly it visually incorporated a mixture of left and right-wing aesthetics. It is very much an artistic statement, invented by members of the art community, which has had little or no influence on actual politics. In your subjective opinion, is the NBP more art or politics? How would you define this phenomenon?

N: The NBP, not in the way it exists now (because now it’s just people shut in a bunker and thinking of themselves as political activists), but in its original form was, of course, an artistic gesture.

All of the gestures that characterized the NBP’s early practices – slapping some politician in the face with carnations, egging the well-known pro-government filmmaker Nikita Mikhalkov, throwing a cake – were all radical broadcasts of the ideas of Limonov, whose ideas were described in his book It’s Me, Eddie (1979): ‘Get the weapon and fight, fight endlessly!’, in such a near-artistic way.

Besides, we know that the NBP is a kind of political game. They have been denied recognition as a political party five times. In fact, I believe now the NBP is the only party that has been recognized as an extremist organization in our country.

А. B: My point is that (going back a couple of questions) Limonov never declared the NBP as a work of art. He said that it was purely politics.

N: We have already discussed that even if an artist does not call his statement art, if it pushes boundaries in this way, then it is art. Besides, in Limonov’s case, he himself is an artist. He is not originally a political activist; he is just playing this character.

А. B: The example of the NBP is also very interesting to me because it is a rather complex case in terms of the political spectrum. Can you comment on what kind of political ideas characterise Pussy Riot? Clearly, Pussy Riot is against police violence, against discrimination, against the endless rule of the same president. But more details – for instance, Pussy Riot’s standpoint towards state regulation of the economy or individual freedoms and private property – are not articulated anywhere in the manifestos. What political views do the members of Pussy Riot have? Do they all have the same political views? Are there any areas of disagreement?

N: Unfortunately, once again, I’m afraid I won’t satisfy your curiosity fully. As I said before, we are not a political party and we don’t have meetings where we discuss involvement in any part of the spectrum. I’ll just say that we are all leftists to a certain extent. Pussy Riot is an extremely big collective, and in order to have some kind of common ground, you should probably follow all of us individually, because it’s pretty clear what ideas we are broadcasting.

А. B: I propose we look at the same question from a slightly broader perspective. Today we’ve already mentioned Pussy Riot, Pavlensky, the NBP, and Limonov, but apart from them, there are many members of the Russian protest art community, such as Dasha Serenko, Katrin Nenasheva, Techno-Poetry, Party of the Dead, and others. You said that there’s no community, that everyone is doing something different. But can you generally characterise what unites all these different people in terms of views and ideas? Or is it possible to have all kinds of views and political ideas in a protest art environment?

N: Once again, I repeat myself: artists and political parties are very different, so I think it’s not very accurate to view artists in terms of what political programme they postulate. If it is protest art, then we are fighting against something. Of course, there are unexpected situations, like with Pavlensky. We thought he was ‘for everything good and against everything bad’, a guy who I think was doing wonderful protest art, wonderful with the limits of his own body and the limits of the political, but in the end he turned out to be a patriarchal man and a sexist, which is why he got his share of condemnation. In general, we are all fighting against roughly the same things (police arbitration, Putin’s rule), some go more into the feminist agenda, some deal more with minorities. Either way, it’s about building some kind of civil society here.

А. B: Last question then. Speaking to art historians and art critics: what is the first thing to pay attention to when we talk about protest art, in order to give the most correct analysis of this movement, or should I say, this phenomenon or genre? How should we, as art historians, work with this now?

N: This is a burning question, because, unfortunately, there has been so little going on in Russian protest art lately, and it’s understandable that the reason for that is the context of repression we are currently living in. What I would like to ask of art critics is that when they think about relevance, that they would not stop looking at the aesthetic component. When an artist makes some relevant gesture, I want us all to keep looking at what kind of images they are working with. I’m talking about, let’s say, the action of crucifying oneself on the cross, which was carried out by activist Pavel Krisevich. There was also an image of fire incorporated into this spectacle, relating to setting criminal cases on fire. While it is wonderful that such a politically potent event has happened, it upsets me a little that it is seen only in terms of the relevance of the event and not in terms of it being a deliberate performance.

This is the same with our actions. With Flags and Policeman Enters the Game, it’s like there’s two positions there: either it’s cool or it’s bad, and no one delves further into it. It’s as if the event happened, and it’s either good that it happened, or it’d be better if it didn’t happen. It doesn’t go any further than this in the criticism I read. It makes me a little upset, because you feel like some kind of adopted child in the art family.

Featured image: Still from video released by members of Pussy Riot, where they take credit for storming the field during the FIFA World Cup finals on Sunday evening, 2018. Image courtesy of artnet.