IMOGEN GODDARD explores the complexities of translating from book to film, and the ways in which these media can work in tandem.

Books are always better than their screen adaptations, right? This is what the literary world tells us, but perhaps the answer to that questions should be: well, maybe. The effectiveness of this intersection has always been an interesting topic of discussion, but has become more and more relevant in recent years with the increasing prominence of films and television in our culture. There are some terrible films created from brilliant books, but is this immediate (and in all honesty, slightly snobbish) reaction always valid? Let’s properly examine whether too much of a book is lost in its screen version, in which case we can toss it aside without a second glance, or if successful adaptations really can be created. Of course, there is a degree of subjectivity in this debate, but we gain nothing from an outright dismissal of a screen adaptation.

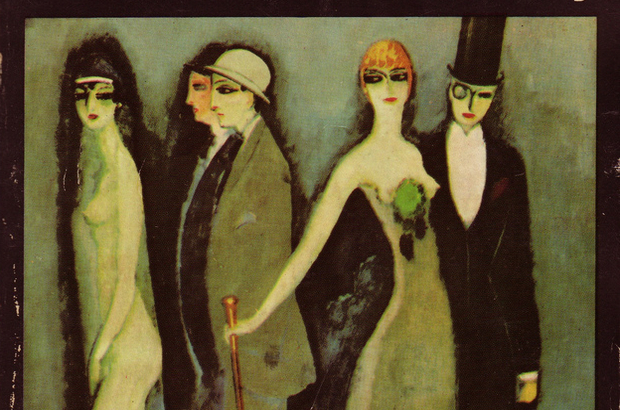

To an extent the novelty and power of literature is lost when viewing its adaptation on the big screen. In Cary Fukunaga’s 2011 adaptation of Jane Eyre we have no sense of the internal fury that makes the novel so poignant, because we are no longer immersed in Jane’s mind. The same is true of Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 The Great Gatsby: something is lost when we don’t view Gatsby through Nick’s eyes, a sensation that no voiceover can replicate. That being said, the stunning visual aesthetic of this film perfectly encapsulates the atmosphere of Fitzgerald’s novel and this, juxtaposed with the contemporary soundtrack, creates, on the whole, an excellent and enjoyable film. Perhaps we should hesitate more before immediate dismissal.

The same can be observed with television adaptations of novels, with directors and scriptwriters generating entirely new plot lines or even characters to fill the abundance of space in a ten-episode series. A prime example of the division of opinions that can come from screen adaptations is Hulu’s 2017 The Handmaid’s Tale series. This took Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel but refreshed it by making it relevant to a modern audience. The characters were given iPhones, the cast was more diverse, and the pre-Gilead era rallies were eerily similar to the anti-Trump marches. Some viewers were disappointed with the manipulation of Atwood’s original material, particularly given that Hulu is making a second series, which will take the story beyond the novel’s conclusion. This is a valid concern, given the moneymaking motives behind it, but the question regarding the modernisation of the material is more complex. Given the disturbing subject matter of Atwood’s novel, it is certainly more engaging to see ourselves and our own society reflected in this relevant and updated production, rather than watching an outdated show fit for an eighties’ audience. The relationship between a novel and its screen adaptation should be malleable, giving screenwriters the agency to manipulate the material as they see fit.

In a discussion regarding manipulation of original material, the relationship between fairytales and their film adaptations is an interesting one. The initial stories – full of violence, gore, and gruesome details – have been taken and made into easily-digestible sickly-sweet children’s films. We see Cinderella without the step-sisters’ toes being sawed off and eyes pecked out, Ariel survives at the end of The Little Mermaid, and Aurora is not raped in Sleeping Beauty. Whilst these changes are naturally made to make the stories appropriate for children, it is rather alarming when we discover the true meanings behind them. The creative freedom to adapt and enhance books and stories is one that should be respected, but in the case of fairytales this is more complex; has pop culture taken this freedom too far, in entirely changing the meanings of the stories? It may seem foolish to deconstruct what is intended as light-hearted children’s entertainment, but it is important to consider that perhaps there is more to it than meets the eye.

At the end of the day, our appreciation of screen adaptations will depend on what we’re looking for – whether that’s pure enjoyment, or a strict following of the given material. But if we can distinguish between the two media, and remind ourselves that the book and the screen versions are different, it leads to all-round more enjoyment and appreciation of culture in general. Whilst some elements of books will not work effectively on screen, there is no harm in appreciating the two different art forms in their own right. In the intersection between book and screen it is undeniable that some elements of literature will be lost – but more will be gained. Can these media work effectively together? Certainly.

Featured image courtesy of flickr.com.