GEORGIA GOOD reviews Ian McEwan’s new novel

Britain, 1982: the Falklands War is beginning, and Thatcher is in Number Ten. It’s a futuristic 1982, with self-driving cars and robotic bin collectors. Yet in some ways, it also feels current: a time of political turbulence, mass protests, and a pervasive online media.

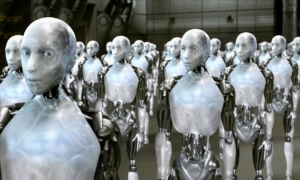

Machines Like Me is both a comment on our time and our future, but it’s set in an alternative past. Alive and thriving, Alan Turing pioneered major technological breakthroughs. One result is Adam, ‘a manufactured human with plausible intelligence and looks, believable motion and shifts of expression’. He is both a being and a commodity, a person and a machine. When Adam wakes up, he belongs to Charlie, a young, isolated man, in love with his neighbour Miranda. The three are drawn into a ménage à trois, a philosophical spiral, and a moral state of ambivalence with a crushing climax. It is at once uncanny, academic, and enthralling.

The novel’s humans are, at times, withdrawn and unsympathetic. Yet this is not necessarily a flaw, and is characteristic of McEwan. In fact, their shallowness throws Adam into relief. When they fall short of our expectations, when they’re incompetent and unmotivated, they allow Adam to shine. He has a depth and vivacity that far transcends his hardware. In the text, he is both a redemption and a threat. He is physically and intellectually superior to Charlie; he is highly intelligent, a romantic competitor, and in a burst of anger, breaks Charlie’s wrist. He’s also emotionally sensitive, sees Charlie as his ‘friend’, and acts as his moral guide. The duality of Adam’s character means, ultimately, such a choice is yours. Yet Machines Like Me, in the end, is tragic. McEwan’s tale recounts a failed experiment, and its conclusions are unclear. At first, it seems prophetic, but by the end, our future is hazier than ever.

Inevitably, Machines Like Me explores the value and meaning of consciousness in the context of AI. Of every person on the page, Adam captivates the most – yet his personhood itself is contentious. McEwan asks the ultimate question of computer science and philosophy of mind: can a machine be conscious? Or, as Turing put it, can machines think? The Turing test echoes throughout the novel; it states that if, when communicating, a machine is indistinguishable from a human, then it can think. Adam, then – intelligent, empathetic, complex – would pass with flying colours. He claims he feels pain, and says he is in love. He writes 2,000 haikus to prove it. He is strikingly uncanny when, for example, ‘he sat naked at my tiny dining table, eyes closed, a black power line trailing from the entry point in his umbilicus to a thirteen-amp socket in the wall.’

For the reader, unsettling questions arise: can a person be so dehumanised, when he’s not human at all? McEwan enters territory which is both timeless and contemporary, as alien as it is familiar. The use of AI for consumerism is not a new concept: virtual robots like Lil Miquela already exist near the mainstream, modelling and promoting brands. As the concept of consciousness blurs, so too does morality. In Machines Like Me, Adam could be a victim, or the property of his owner; he occupies the space in between. Charlie may be a criminal, exploiting a sentient being for personal use, or simply a consumer using a product. McEwan revels in this ambiguity. He presents a neglected little boy, a scarred young woman with a dark past, and a man with his own insecurities. When they cross paths with Adam, a series of events unfolds that stirs up issues from personhood to justice and consent. The reader could be outraged, indifferent, or lost in the illusionary chaos of a hypothetical world.

This is not a robot novel. According to McEwan, it is not even science fiction. Instead, it centres on humanity. The writing is highly self-conscious, a meditation on the human condition. Creations like Adam, after all, are reflections of ourselves. Adam has read everything ever written; through his voice, McEwan considers ‘the entire history of human self-regard.’ By analysing the past, he predicts the future – a vast human narrative, fuelled by the creative, destructive power of our own minds. ‘The mind,’ he writes, ‘dethroned itself by way of its own fabulous reach.’

This is one paradox of many, which collectively make up our psyche. Machines Like Me is preoccupied with tragic, inexplicable contradictions – and how they undermine technological progress. Adam is superior, in many ways, but he’s ignored and discredited, his curiosity frustrated, his opinions dismissed. He has the intellect to solve Miranda’s problems, but this puts him at risk: as he learns, tragically, we can’t always listen to reason. Adam and his brothers and sisters, strewn across the world, simply can’t come to terms with the insensible realities of the human mind. The absurdity is too much: we are, McEwan writes, ‘a hurricane of contradictions’. Millions suffer from diseases we can cure; we’re destroying the planet we depend on to survive; we love living things, but facilitate extinction and abuse. The machine response is unsettling: not only confusion at the cruel, fundamental irrationality of things, but also enormous pain. Other Adams and Eves, we learn, are driven to destroying themselves.

In light of this, AI acts as a mirror. These are perfect, rational, self-conscious beings – so how can they exist, in a world as imperfectly human as ours? How can they face Virgil’s lacrimae rerum, the tears in the nature of things? For the reader, perhaps, this is a wake-up call. We live alongside suffering, and deny our hypocrisies, to ignore our own absurdity. We need artificial eyes, eyes with ‘tiny blue rods’ that see more clearly, to empathise, analyse and moralise all at once. For McEwan, then, Adam and his kind are more than a mirror: they are ‘a dream of redemptive robotic virtue’. He theorizes on the programming of such AI, how it would be faced with a thousand moral dilemmas and, slowly, develop its own solutions.

So perhaps, in the end, all is not lost. Complexities aside, Machines Like Me emits a faint philosophical hope. Somewhere, there’s a moral compass just beyond our reach. If AI can find it, perhaps it can save us from ourselves – if we allow it to.

‘Machines like Me’ is published by Vintage (£12.99)

Featured image source: ianmcewan.com