EMMA GABOR discusses how Nikki de Saint Phalle’s Shooting Paintings utilise sensations of violence and rebirth to promote a journey of catharsis for both the artist and the spectator.

Her ambition is not to become the master of the negative forces around her and in her, but rather to confront them again and again and become friends with the powers of darkness. – Pontus Hultén.

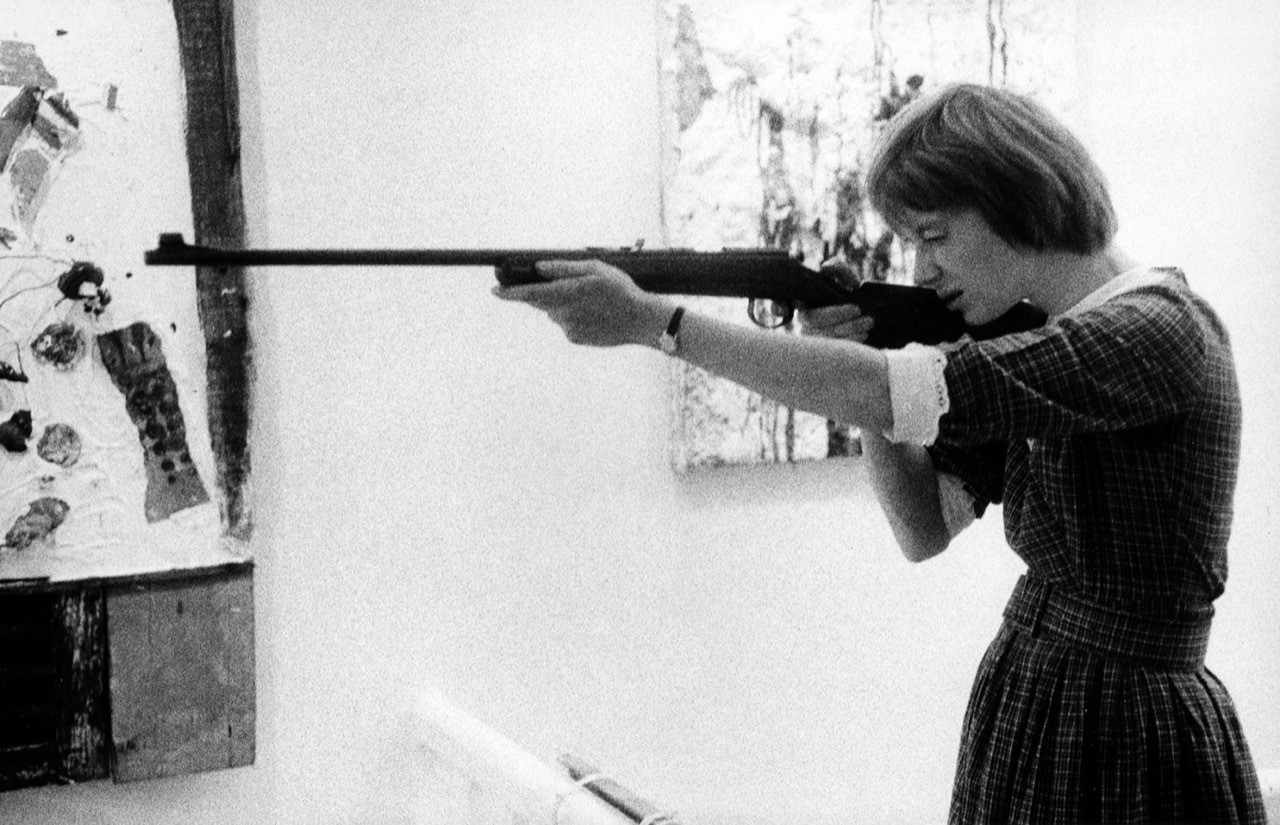

The above quotation exemplifies the process of catharsis that Niki de Saint Phalle underwent through the creation of her infamous series of Tirs, or Shooting Paintings (1961-63). This series began in 1961 against a backdrop of political violence in France, a consequence of the war in Algeria. The process of creating a Tir was uniquely compelling; a canvas was placed upright, facing the artist, with objects ranging from shoes to pieces of wood glued onto it. Hanging above the canvas were cans of paint, which waited obediently to be shot at by Saint Phalle’s gun, the paint eventually spilling onto the surface of the canvas having been hit by her bullet. Often the rifle’s bullets penetrated the canvas and tore them open. This process of creation was a counterintuitive, destructive act; yet, through demolishing the objects she placed within her work, and indeed the canvas itself, she generated an artwork. One of her most famous renditions of this series took place at the American Embassy in Paris. Eventually, in 1962, her series moved to the United States, where Saint Phalle gained her great fame.

A connection has frequently been made between Saint Phalle’s paradoxical destructive process of creation and the artist’s process of overcoming her traumatic childhood, involving years of sexual abuse at the hands of her father and a strict Catholic education. Growing up within an aristocratic family of bankers, which only added to the strict conservatism of her upbringing, Saint Phalle later attempted to reject these experiences through her artistic practice, which turned violence into something productive, and indeed something she had control over.

The term ‘sensation’ is something that brings to mind physicality and touch, as well as an individual’s deep inner feelings. Saint Phalle’s Tirs excite a violent and ephemeral, yet interestingly childlike sensation in the viewer. I believe this notion of sensation is central to Saint Phalle’s work, as it opens the conversation towards performance, womanhood and catharsis.

Sensation in Saint Phalle’s Shooting Painting American Embassy (1961) appears in many forms. In a straightforward sense, there is the ocular sensation of the artist’s bright colours, and peculiar shapes and forms. Yet, it is through her actions that she brings this sensation alive. ‘I shot because I was fascinated watching the painting bleed and die.’ Saint Phalle likened her work to death and therefore in many ways, war. Yet unlike war’s conclusive and definite nature, the artist’s painting is reborn through its demolition. As she puts it, this is a ‘war without victims’. From one perspective, this experience is deeply personal; the painting dies for Saint Phalle’s own emotional evolution only, so that she can reemerge stronger, leaving behind the trauma she just ‘killed’. Indeed, as expressed by Carla Schulz-Hoffman, ‘the real reason why she turned to art thirty years ago was that she needed to devote attention to herself.’

While her Tir performances were notably inward-looking, a profoundly emotional response was undeniably triggered in the audience also. The spectators of this performance also experienced some form of death and rebirth, a catharsis – something I believe is still accomplished in the present by images of her work. Yet, because we all have our own ‘unique’ emotional baggage and experiences, the rejuvenation we undergo when viewing this work will differ; our experience of this performance is deeply subjective in its emotional impact. The victim and the victor are the very same individual: Saint Phalle, but also the individual members of the audience who go through this process with the artist. Instead of shielding the audience from life’s harsh realities, Saint Phalle forcefully emphasized this exposure, to a point of great Artaudian ruthlessness. This confrontation with violence then frees the spectator as it does the artist.

This catharsis is also present as a physical, material existence on the canvas. The paint is dripping, flowing everywhere, as though there were no boundaries between it and the objects glued onto the canvas. Additionally, some objects have also been shot into, either by accident or perhaps precisely on purpose; we will never know the intention of Saint Phalle’s aim. However, despite its chaos and material expurgation, the resulting canvas was always a coherent whole. The sensations experienced throughout the violent act of shooting manifest themselves on the canvas; through their lack of logic and reason, they birth a surprisingly intelligible entity. Indeed, Saint Phalle’s Tirs are both visually sensational and filled with an emotional sensation. The artist’s past is being realized and released through a psychological journey, an intense Aristotelian catharsis which the artist and the spectators are both subjected to.

The act of pulling a trigger is one inextricably connected to aggression. And while anger is usually an emotion with a negative connotation, here, violence has been reappropriated, the process culminating in a beautiful sensation of satisfaction and peace. Saint Phalle’s Shooting Paintings originated from her desire to purge herself from her violent past. Saint Phalle grew up dominated by male figures, being degraded by the men closest to her: ‘There I was, an attractive girl (if I had been ugly, they would have said I had a complex and not paid any attention) screaming against men in my interviews and shooting with a gun’.

Saint Phalle’s art was always reductively considered in relation to her gender; her achievements and creativity were often depreciated on account of her being a woman. As she was considered to be very feminine and attractive, the significance of her Tirs was frequently limited to their connection with her body (we have to remember that in 1961, a woman in France could not yet have her own bank account – Saint Phalle was no exception in this culture of subjugation). To quote the artist: ‘I wanted the world and the world then belonged to MEN… I felt jealous and resentful that the only power allotted to me was the power of attracting men.’ Saint Phalle therefore wanted to seize control through performance, taking back control of her body. She was no longer an eroticized spectacle, but a site of violent creative potential. She parodied female objectification during her performances, picking up a rifle as a feminine, attractive young woman, and reappropriating this masculine object. She willed to provoke, to bring to the forefront a feminist discourse, for she had the artistic and (un)fortunately, emotional power to do so.

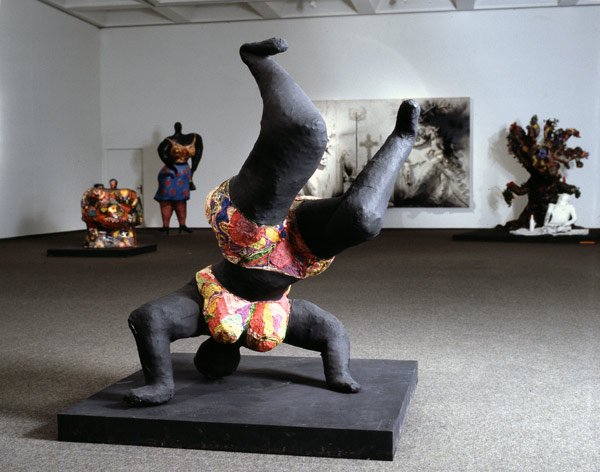

Saint Phalle was one of the first female artists to gain recognition amongst the male-dominated art world of the 1960s. She made the female body a site of creation. Indeed, after achieving notoriety following her Shooting Paintings series and becoming a so-called ‘avant-garde rebel artist’, she turned to her famous Nanas: a series of sculptures exploring the roles of women, that would eventually make feminist art history.

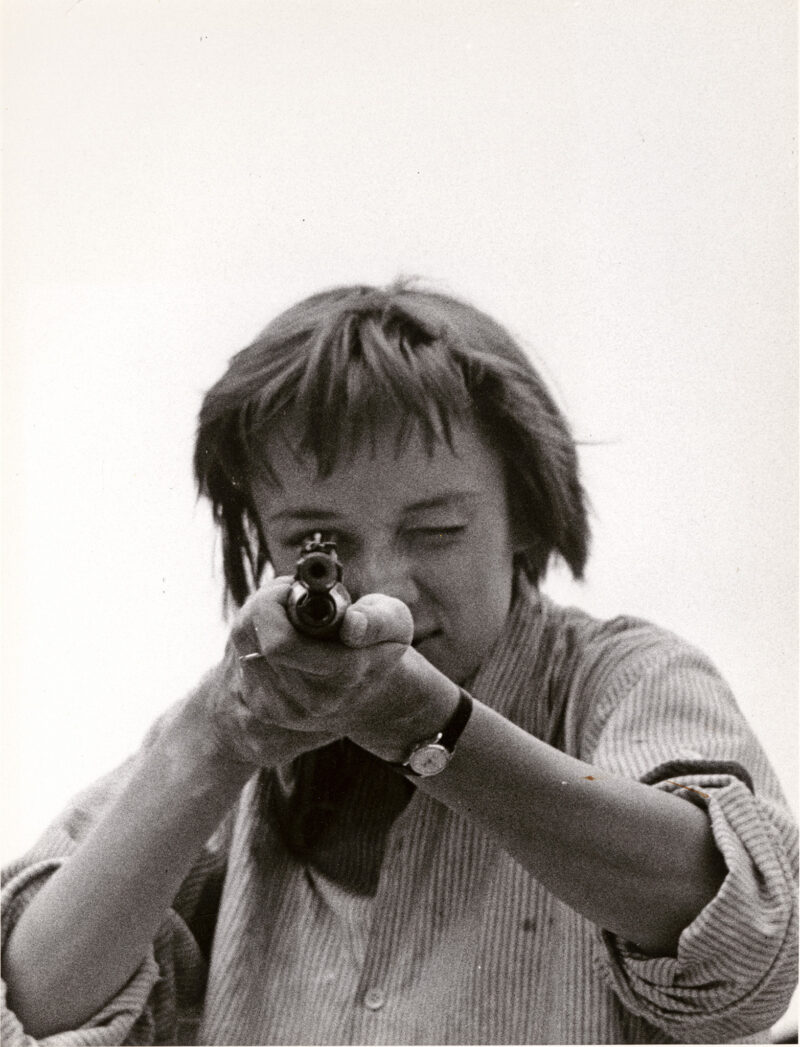

Featured image: Portrait of Niki de Saint Phalle at work, 1961. Image source: The Walker Living Collections Catalogue.