BORI PAPP reviews Andy Warhol at the Tate Modern and considers the methods used to represent the lives of such canonical figures as Warhol.

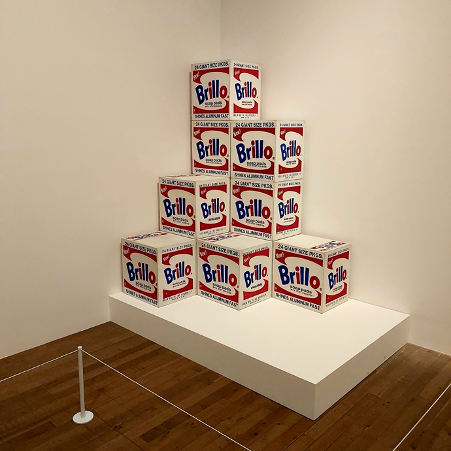

If you asked me a week ago to tell you the first thing that came to mind when I thought of Andy Warhol, I would have said Brillo boxes. While I was aware of his more famous works, such as his Marilyn Diptych or Mao portraits, I knew little about the artist himself.

The exhibition Andy Warhol at Tate Modern is centred around Warhol’s life in conjunction with his art. The resulting experience acts like a particularly immersive biography. As you enter the exhibition space, the first thing you see is a wall of illustrations. These are quick-handed, simple drawings, a few lines in black on white backgrounds, depicting mostly unidentified young men, the careful placement of the lines suggesting closeness to and affection for the subjects. With these sketches, we are introduced to the unlikely canonical figure of Warhol, an openly gay man in 60s America, the child of a low-income immigrant family, who would eventually take on and command the New York art world.

As a viewer, the exhibition pulls you in very quickly. The setup is relatively conventional: each room represents a different period in Warhol’s life. The surroundings are minimal, the simplicity of which allows you to focus all of your attention on the art, and at times truly submerge yourself into the mind of the artist. As you walk through each stage of his life, you gain insight into the experiences that shaped him as a person, as well as the various factors that influenced the art he created. In this respect, the exhibition is very successful: through a combination of paintings, films and iconic objects such as Warhol’s silver wigs, it summons the cultural, social and political atmosphere of Warhol’s America.

Warhol’s America was not a comfortable place. Consumerism permeated everything, celebrity culture was thriving, people were fighting vehemently for racial justice and the gay rights movement was in its early stages. Warhol, whose footsteps you follow in as you walk around the space, was obviously keenly aware of what was going on around him. As you step into the second room, for example, you’re confronted with his Marilyn Monroe screenprints (1962). The longer you look at these works, the more disturbing they become. The way Marilyn’s picture begins to fade is a biting indictment on the fleeting nature of fame. But Marilyn’s portrait is still here, her fleeting moment in time immortalized and frozen on the canvas. Fame is fragile, fame is constructed, fame is momentary. Yet Warhol himself pursues, and indeed, represents it.

Another painting in the same room that I was instantly drawn to was Pink Race Riot (1963). This work is an enormous canvas, featuring photographic reproductions from an issue of LIFE magazine, documenting civil rights demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama that same year. The bright red background evokes a sense of fear, which is hammered home by the imagery of the police dogs growling at the viewer from a distance of almost 60 years. Despite this historical separation, the work was woefully reminiscent of police brutality at Black Lives Matter protests today. I stood in front of it for a while, stumped by the realization that if I didn’t know the date on these photos, I would not be able to tell when they were taken, not even down to the decade. 1963? 2020? It feels like one and the same. In addition to the feeling of unease it induces because of its continued relevance, the painting is also a testament to how much Warhol cared about politics. While many of his works from this period (Green Coca Cola Bottles, Brillo Box, etc) have political dimensions to an extent, they are primarily no more than a poke at the backwardness of consumerism. Pink Race Riot, on the other hand, engages with an inherently political subject. It is also an early hint at Warhol’s later fixation with the theme of death.

The next room is not as minimalistic as the rest. The walls are covered from floor to ceiling in shiny silver, recreating the look of Warhol’s studio, The Factory. As a meeting place of artists and musicians, it functioned as a hub of New York counterculture. In the room adjacent to this one, you find a cluster of silver clouds, floating just out of reach above your head. You learn that it was around this period that Warhol started to consciously and purposely curate his own status as a celebrity, leaning more and more into the silver aesthetic (walls, clouds, wigs). He also dabbled in multimedia projects, the culmination of which was a performance titled Exploding Plastic Inevitable (1966), which involved music by The Velvet Underground, dance and performances by some of the ‘superstars’ Warhol’s Factory produced, and screenings of films by Warhol himself. Unfortunately, EPI cannot be seen at the current exhibition (the room where it was being screened is now closed because the space does not allow for appropriate social distancing). But even without it, Warhol’s obsession with fame is made abundantly clear, as well as the great lengths he went to in his efforts to create his own circle of ‘superstars’.

The exhibition comes to a halt after this point, as we learn that Warhol was shot in the stomach by one of the regulars at his Factory – a woman named Valerie Solanas. Only a short paragraph on the wall informs the viewer that Solanas was angry at Warhol because of a dispute over a play. Considering all the detail the exhibition goes into regarding other milestones in Warhol’s life, it feels like the reasons behind this one event are dismissed unduly quickly. It is, of course, a sensitive subject, but the impact it had on Warhol’s later life was so significant that I think it should have been addressed more.

After being shot, Warhol grew very concerned with the subject of death; interestingly, many critics consider Warhol’s works from the 70s to be weaker than his more famous ones from the 60s. The exhibition does a good job at showing what else Warhol was doing during these years, besides creating arguably less-than-stellar art: in addition to publishing a magazine, he was occupied with countless TV appearances. One thing that really surprised me was that he appeared on Saturday Night Live – who knew that has been around so long?

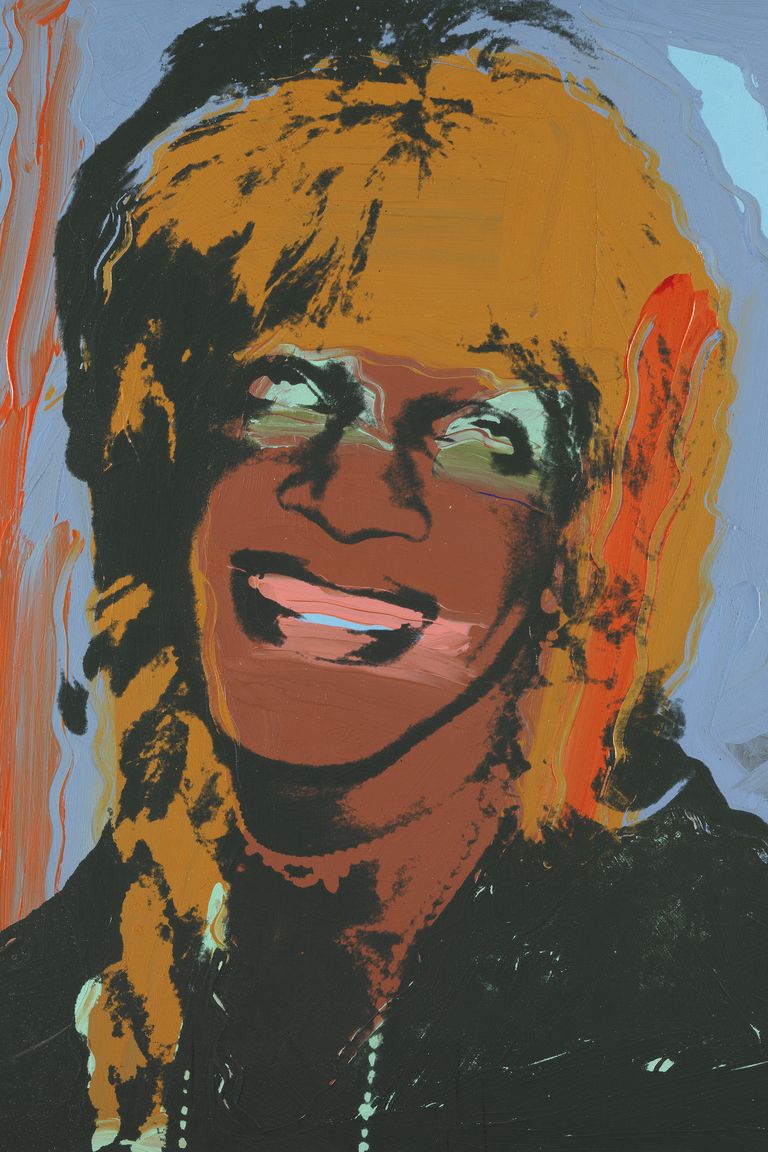

And while I can see why some of Warhol’s later paintings didn’t earn the same critical approval as his earlier works, one series which I think deserves more recognition is his series of portraits representing anonymous Black and Latinx drag queens and transgender women. Warhol invited these individuals to sit for him in his studio for a compensation fee. There are glaring questions regarding the power dynamics of this, which the exhibition fortunately does acknowledge in some capacity, before then proceeding to dance, rather clumsily, around the issue. Despite the awkwardness of this, the power of these works is not lost: the portraits speak for themselves, and the bold brushstrokes in clear, primary colours preserve the character of these people much more successfully than modern commentary is able to do.

The final room of the exhibition is completely occupied by one painting, which draws attention to a side of Warhol we haven’t explored yet: his faith. Entitled Sixty Last Suppers, the painting is composed, sure enough, of sixty reproductions of Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece The Last Supper, all in black and white, taking up an entire wall. What struck me most about this was how Warhol transformed Leonardo’s painting into a subtle but powerful expression of queer longing. Reduced to its essentials by Warhol’s signature method, repetition, it is ultimately just a group of men, very close to each other, conversing and having supper together. Knowing that Leonardo was very likely homosexual adds another layer to this interpretation. At the same time, it raises a myriad of questions about Warhol himself. Did the clash of his homosexuality and his religious beliefs worry him? If they did, was he ever able to overcome or reconcile this? These questions are never resolved in the exhibition, which left me feeling very unsettled, perhaps reflective of the headspace of the artist at the time.

This feeling of unease is present throughout the second part of the exhibition. Ideally, you would need to see it twice to put the two eras of his life into perspective. Nevertheless, it’s a very good introduction to Warhol, and there is a strong case to be made that these introductions are necessary every once in a while, so that younger generations can get acquainted with those whose works shaped the artistic production of today. And they should, because if there’s one very obvious takeaway from this exhibition, it is that we haven’t changed that much since the 60s. Excessive consumerism is still a problem, systemic racism and prejudice against queer people is still around. We have come far, but we still have a long way to go.

Andy Warhol at Tate Modern is open until 15.11.20.

Featured image: Andy Warhol, Sixty Last Suppers, 1986, acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen, 116 × 393 inches (294.6 × 998.2 cm). Image source: Gagosian.