LILLIAN CACCIA reviews Electronic: From Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers at the Design Museum and muses upon her nostalgia for the club scene in times of social-distancing.

Since the 2000s, electronic music has earned its place as a major artistic movement in modern-day global culture. In this first major exhibition on electro, the Design Museum explores the genre’s connections to contemporary art, fashion and design from across the world, from Berlin to Tunis, and Buenos Aires to Los Angeles. The exhibition details not only the chronology of electronic music, but showcases the beauty, power and art of the sonic experience.

Entering the exhibition, the space immediately evokes the atmosphere of a Berlin nightclub. The air is close, the dark spaces filled with low spotlights and exposed metal scaffolds. French DJ Laurent Garnier thumps in the distance whilst the lights casts coloured shadows on the scattered few allowed in.

I am initially met with Andreas Gursky’s photographs of revellers at Dusseldorf’s Union Rave in 1995. The party-goers stretch on for an infinity to the back of the photo. I am hit with a pang of nostalgia when my first thought is ‘what a lack of social distancing’, and then, of a burning desire to dance like them.

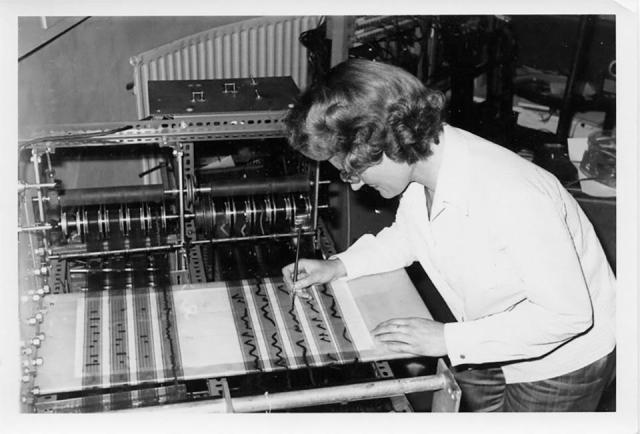

The exhibition turns to a chronological development of electronic music, with early pioneers dubbed ‘the mad scientists of sound’. The display showcases early science fiction-esque instruments frequently revisited in this sub-genre, including the Telharmonium, the Theremin and Ondes Martenot. Originally invented in 1928, the Ondes Martenot (a digital keyboard that creates whirring sounds) is still in use today by Daft Punk and Radiohead. Included in this section is a tribute to the iconic composer Daphne Oram, shown painting data onto film, accompanied by a 2019 video performance of her iconic work Still Point, considered to be the first composition that combined acoustic orchestration with live electronic manipulation.

The curated space exhibits the modern creative minds of individuals such as fine artist Xavier Veilhan, and pioneering composer and artist Christian Marclay. The iridescent surface of Detroit native Jeff Mills’s ‘Supernatural Costume’ glints as if it has been transported from outer space; the amorphous red Chemical Brothers costumes are equally as celestial. One of the mesmerizing highlights of this section is the CORE installation by 1024 Architecture, which consists of 81 sound reactive light rods that pulse to Laurent Garnier’s playlist in a darkened room. Headphone jacks pepper the exhibits, allowing you to tune into video, animation and pure sonic experience throughout. Many of the galleries are broken up into smaller spaces, creating strangely intimate listening experiences.

Electronica is never just about the music. It is also about the dancefloor and those who dance to its rhythm. This exhibition poignantly brings together the global celebration of this genre in one place, moving through the dance floors of Detroit to Chicago, Paris to Berlin. In the UK, the Manchester electro scene was pivotal in catapulting electronic bands into the spotlight, with clubs like the Haçienda acting as the host venue for pioneering acts. Whilst I felt a comprehensive overview was given about the Western and European narrative, electronica owes much of its origins to afrobeats, jazz and world music. The exhibition could have benefitted from more focus on African, Asian and South American scenes and their influence on electronic music.

Electronic dancehalls and the music played within them often went against the political tides of the time. The exhibition references the iconic acid house smiley face, showcased in the work of Jimmy Cautyas, singer of seminal 1980s band KLF, who helped canonise this iconic symbol by using its iconography on a riot shield. Electronica and club nights have always provided safe spaces for freedom of expression, a haven for marginalised groups such as the LGBT+ communities. This exhibition provides a poignant reminder that these spaces are under threat, detailing how 60% of gay nightclubs have been shut down in the past 20 years.

The exhibition concludes with an immersive experience of ‘Got to Keep On’ by the Chemical Brothers, curated by their long term show directors Smith and Lyall. Complete with strobe lights, and gigantic on-screen visuals, you are simultaneously alone yet encompassed within a totalising and intoxicating stimulation of the senses. I left dazed and wildly energised, while unfortunately realising that that was the closest I will get to raving for a while.

In this divided society, music has become much more than a sonic experience. It is a global movement, a community of celebration. Having been isolated for so long, I felt overwhelmed by the passion, beauty and raw power of creativity, and left the space affirmed that art and music really can conquer all.

Electronic: From Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers will run at the Design Museum until 14.02.21.

Featured image: Installation view of The Chemical Brother’s ‘Got to Keep On’ video. Image courtesy of Londonist.