IZZY DAVIES reviews Refugees: Forced to Flee at the Imperial War Museum, considering implications of voyeurism and sensationalism in the representation of such individuals.

Right now, over 79.5 million individuals have been forcibly displaced by persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations, with one person becoming displaced from their home every 3 seconds. This is a record high and is roughly equivalent to the entire population of the UK being forced to flee their homes. However, in 2018 the UK received only 6% of asylum applications made in the EU. Despite this fact, media coverage has tended towards a sensationalised, fear-mongering approach of representing this crisis, as popularised through the 2016 pro-Brexit campaigns, and the Conservative government’s hostile policies. As Simon Offord, IWM curator, notes, ‘now more than ever it’s important for the IWM to bring 100 years of refugee voices and experiences back to the forefront’.

The exhibition Refugees: Forced to Flee explores the past century of refugee experiences through displays of photographs, oral histories, documents, objects and infographics, starting with Nazi Germany’s persecution of the Jews in WW2 and taking the viewer up to the present day. Importantly, the exhibition also attempts to highlight the UK’s response to refugee crises in the past 100 years. Perhaps conveniently, this 100-year period leaves out the most shameful parts of British history in regard to displaced people: the colonialist persecution, violence, displacing and trafficking of indigenous peoples in present-day Africa, America and Australia. Certain aspects of the UK’s involvement are also not addressed – most noticeably the role of foreign intervention in funding and provoking civil war, ISIS and upheaval in the Middle East and the ensuing refugee crises. The weight of these historical exclusions is made all the more uncomfortable in the wake of the BLM chants that filled central London over summer – the UK is not innocent and it’s silence here is violence.

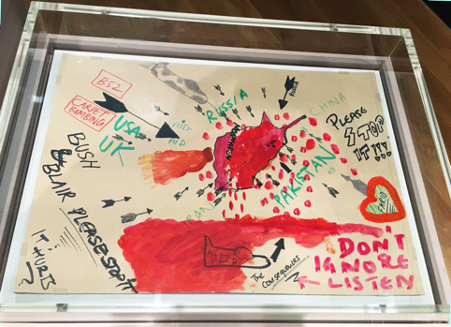

The first room introduces the question, ‘Could you leave everything behind?’, placing us at the starting point of our journey, mirroring the one taken by every refugee. We begin at the home, exploring a selection of memories, photographs and artefacts. A series of mundane objects (a teddy bear; sheet music; a child’s painting), reminiscent of the famous Jewish Museum Berlin’s personal item collection, are accompanied by vivid, high-resolution photos in dug-out caverns on the wall, requiring the visitor to lean in and view the image close up. This design forces the viewer to interact more intimately with the work while also providing the feel of a private space for contemplation. Overall, there is a hushed, library-like atmosphere. People look, listen and read in silence, with groups of guests showing very little interaction or communication: an atmosphere of respect and contemplation is prevalent.

In this room we are provided with important exposition: the definitions of migrant, asylum seeker, refugee and displaced person are explained in concise labels alongside summaries of some notable conflicts. A curatorial touch that resonated with me was the inclusion of photographs showing locations as they were pre-conflict. This choice is a stark difference to the typical sensationalised, exploitative displays of poverty, grief and violence that normally represent these places in the Western media. The room is meant to represent ‘home’, as it is perceived in the minds of those forced to flee from it, and nostalgia is an important part of this portrayal. This approach falls very much in line with the museum’s ethos of respectful commemoration: the exhibition makes a conscious effort to be self-aware and even critical towards the IWM’s own history of commemoration and glorification of war. This is a trademark of the IWM; this museum founded in the context of imperialism, colonialism and militarism is well-accustomed to exploring the consequences of its inherent focus. ‘This is happening right now’, we are told unmistakably in the first room.

There is a creative, if a tad kitschy, attempt to echo the chronological journey of a migrant through the designs of each room. The patterned wallpapers of the home are ‘burnt’ away to reveal skeletal, wooden rafters as we encounter ‘conflict’. The seriousness of the subject seems slightly at odds with the playful, doll’s house style, especially when encountered with large questions such as ‘what would you take with you?’ plastered on all surfaces. The questions are clearly meant to encourage empathy; but alongside the wall designs, they result in a childish appearance, distracting from the real experiences the exhibition claims to be elevating, and verging on becoming condescending to both the viewer and the subject they speak on. The initial design suggests a sense of interactivity, but this half-hearted attempt to make the exhibition more ‘family-friendly’ falls a little flat. More effective are the following rooms, where deep blue walls create an all-enveloping feeling of the journey over stormy seas, abruptly followed by the harsh, clinical hospital-like walls representing the Home Office on arrival to the UK.

Despite the unusual curation at times, accessibility had clearly been taken into account: the high contrast labels consisted of clear, modern fonts with spacing and bold accents to break up large chunks of text. Another highly effective choice was the repeated use of infographics to portray statistics and dates in a clear manner, accessible to all ages. These were cleverly utilised to break up large amounts of data into readable and interesting designs.

The exhibit’s style was more educational than artistic, with the photographs often taking a back seat to the many other objects, videos and infographics in each space. The subjects of the photography were realistic, with some unflinchingly brutal in their depictions: an Iraqi family under fire, a Belgian woman killed in a German air raid, an overloaded refugee boat in distress in the Mediterranean. To have these photos in a purely artistic environment would have been deeply uncomfortable and exploitative; the debate still remains whether they are necessary in any environment, as discussed poignantly in texts by Graeme Green and Mike Osbourne.

Although I was glad not to see Nilüfer Demir’s 2015 headlining photo of three-year-old Alan Kurdi washed up on the beach, I questioned whether these photos were any better. Inherently, they were all about capturing suffering and attempting to shock and provoke viewers. Susan Sontag’s extensive writings on the subject of exploitative photography make the point that the continuous media stream of suffering, pain and violence has less moral impact the more people are exposed to it – ‘“concerned photography” has done at least as much to deaden conscience as to arouse it’. Do we need to keep viewing these exploitative photos of others’ suffering? Or does this make us all, as Sontag would call it, ‘voyeurs’? The obvious counterargument is that people need to witness these realities to be shocked into compassion and action. But given that the photo of Alan Kurdi became an international point of discussion in 2015 and five years later refugees are still dying every day on dangerous, unsupported journeys, witnessing is clearly not enough.

The final rooms, titled ‘Refugees welcome?’, explored ideas of integration and acceptance into the UK. There were heart-warming photos, such as that of Gulwali Passarlay, an Afghan refugee, carrying the Olympic torch for London 2012. However, such images were also juxtaposed with depictions of the darker side of the UK’s refugee policies – a photo from 2003 showed a group of Afghan men protesting against deportation outside Downing Street. The final room featured a collaboration with artist Shorsh Saleh, a refugee from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. His beautifully woven tapestry rugs imbued with metaphorical meanings were a highlight of the exhibition, combining his traditional heritage of carpet weaving with powerful, resonant metaphors of the hardships he had faced as a refugee. This collaboration room was one of four dotted around the exhibition, featuring work from immigrant artists living in the UK.

Complementing the main exhibition were two installation ‘experiences’: A Face to Open Doors, an interactive, digital border-control experience created by award-winning artists Anagram, and Life in a Camp, an immersive video installation by filmmaker Lewis Whyld and journalist Elinda Labropoulou providing an intimate view of the makeshift Moria camp on the Greek island of Lesbos. While Anagram’s work was a bizarre and thought-provoking experience (and one for which I don’t want to give too much away), by far the most memorable was Life in a Camp. The piece consisted of a small room featuring three full-scale wall projections of film footage on a loop, simply showing the daily, mundane activities of life in the Moria camp. Filmed in 360°, the installation transported the viewer into the camp, its residents now going about their daily lives around you. The viewing experience was an emotional and profound one, and was in many ways (perhaps due to the intimate and immersive nature of film as a medium) more successful than the main exhibition in doing what I hope would be one of the key aims of any display like this – humanising the people it portrays.

The film’s poignancy and impact clearly came from its intimate portrayal of refugee life, in a similar vein to many of the objects and photographs from the main display. But to what extent had these displays benefited the communities they were portraying? There was collaboration in the artists’ works and the research videos, but it was not clear enough how exactly these would benefit the refugee communities, aside from the obsolete idea of ‘exposure’. If, as I was left to wonder, there was no close work with refugee communities, – was this display just another example of exploiting suffering to create an exhibit? Having said this, all the research and writing above was motivated by this exhibition, so it has at least inspired one person to action.

For anyone else ‘inspired to action’, please check out Refugee Action and donate today or get involved as a volunteer.

Refugees: Forced to Flee at the Imperial War Museum plans to reopen on December 3rd 2020 and will run until May 24th 2021.

Featured image: Promotional image for Anagram’s immersive experience, A Face to Open Doors, an interactive installation commissioned by the IWM London for the Refugee season of events.