MARISA BECIROVIC reviews Sin at the National Gallery, reflecting on how our contemporary conception of sin has strayed from its historical underpinnings.

Wrongdoings, misdeeds or falls from grace. However you put it, the offences of humanity boil down to a single, age-old concept: sin. The indulgence of this topic is hidden behind its curt label: the term ‘sin’ encompasses so many aspects of human nature and society that artists have long been drawn to exploring. The National Gallery now brings us an exhibition exploring the complexities of sin.

This collection of works leads the viewer through biblical depictions of Adam and Eve, to chaotic scenes of adultery and other improper behaviour in 18th-century paintings, and contemporary reflections on the crimes of humanity. The exhibit does justice to the varied understandings of the concepts of morality and indecorous behaviour we hold as a society. While it highlights the Christian origin of many of our ideas of sin in the western world, it is not difficult to find similarities in other religions, illuminating the transferability of such concepts to the wider nature of humankind.

From a modern perspective, the very notion of sin has transgressed somewhat from the individual to the responsibility of general society. Our group propagation of behaviours and beliefs has bred inequalities and violence amongst the masses. The exhibit takes us on a journey exploring the multitude of forms sin adopts, and ultimately begs us to consider the part we play in it all.

The way in which many of us have faced the concept of sin in our own lives has been through religion. It is a fundamental teaching of many religions such as the Islamic principle of haram, or the 613 commandments dictating morality in Judaism. The exhibit, however, focuses on the Christian portrayal of this concept, namely through the depiction of Adam and Eve’s fall from the Garden of Eden, having spoiled themselves with the forbidden fruit.

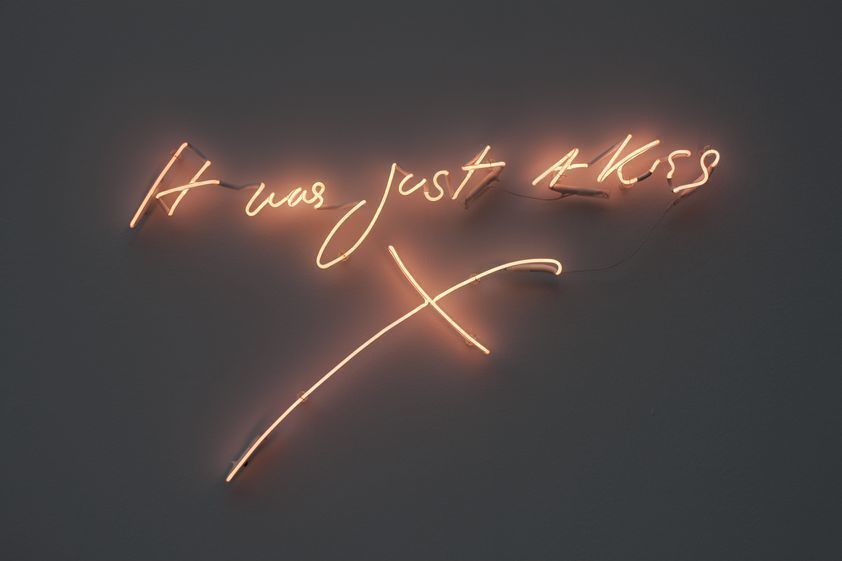

This portrayal of the original sin of man, as seen for example in Lucas Cranach the Elder’s painting Adam and Eve (1528), has become iconographic in the world of art. This symbol of sin, portrayed simply through human form, goes beyond the act of consumption. It shows that sin is encompassed in the very nature of humankind and therefore reveals its universality – a universality that must prevail in art. The mixing of these ideas is demonstrated in Cranach’s painting Venus and Cupid (1529), which blurs the lines between the admired classical figures of mythology with the sinful Adam and Eve. He provokes the idea of enjoyment in sin, evoking sexuality in the scene. The composition of his subjects purposefully mirrors that of his former painting, explicitly linking Eve, the first woman and symbol of purity, with Venus, the goddess of love, sex and desire. The exhibition places Tracy Emin’s installation It was just a kiss (2010) close by to these works, bringing in a modern spin on the idea of desire, guilt and sin. She flashes the words ‘It was just a kiss’ in bright pink neon in this installation, mirroring the changes in cultural perception of sin, especially regarding female sexuality.

Whilst we may recognise sin to be a feature of humanity, it has certainly not been ‘accepted’ throughout the centuries. When most of us think back to the 17th or 18th century, we might imagine good posture and polite conversation. We hardly consider the certainty of gossip-worthy sinful behaviour that occurred. Hogarth’s painting Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête (c. 1743) is refreshingly candid in its depiction of a couple’s chaotic household, hinting not so subtly at suggestions of adultery and other forms of unruly behaviour. Similarly, Steen portrays unsupervised children gone wild, surrounded by animals and with cheeky grins on their faces, in his Effects of Intemperance (1662), elaborating on this very natural state of ‘sin’ or improper behaviour when we put down our guard and relax. It is amusing and engaging as we recognise the humanity in this frivolous descent into animal instinct and impulse.

Looking deeper, however, there is historical injustice when it comes to the classification of sin. Both biblically and peppered throughout art history, the apparently intrinsic role of women in the wrongdoings of man and humankind has been highlighted. For wasn’t it Eve, and not Adam, who took the first bite of the forbidden fruit? The concept of sin, amongst other things, has historically been used as a tool to demonise women, reducing their rights, and denying them the human autonomy to experience deserved by all. The one woman who escapes the label of sin is the Virgin Mary, depicted in Velázquez’s painting The Immaculate Conception (1618-19) as floating above the world in serenity. While this one exception is made, the rule remains for centuries that women are unjustly burdened with ideas of sin.

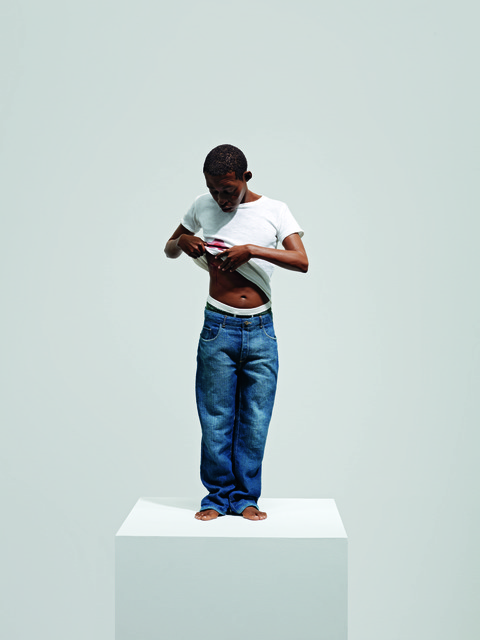

As feminism and other social movements have emerged in the last hundred years, we have, as a society, begun to question the origin and validity of sin. The tables have turned. A culture of introspection and finding fault in our own actions, rather than the pointing of fingers at others, has slowly become more common. The gain of female suffrage, of the abolishment of slavery, of the introduction of low emission zones in congested cities, have all revealed to us that some sins lie with masses and require huge cultural shifts to be rectified. In light of the recent Black Lives Matter movement, Ron Mueck’s piece Youth (2009-10) poignantly spotlights the crimes of today. The artist has depicted a young Black man, his lifted shirt revealing a stab wound. This work draws a link to Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano’s work The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1502-04), which can be found in the main part of the National Gallery, a painting in which a resurrected Jesus stands as its central figure, with the same wound in his torso as in Mueck’s sculpture. The use of biblical allusion adds weight to the piece. It ricochets back to the idea of Jesus ‘dying for our sins’ thousands of years ago. However, in actuality, people continue to die for our sins every day as a result of racism and social injustice.

While we often joke and make light of the idea of sin in a somewhat modern rejection of the institutionalised fear and oppression of religion, the core of it remains something worth thinking about. As is the nature of humanity, we have evolved over time and developed different relationships with religion, with art, with society itself. As these relations change, as the Sin exhibition poignantly pinpoints, so does our concept of morality and social responsibility. In the end, the exhibit gives us an overarching insight into the complicated concept of the crimes of humanity, and honours the subjectivity these evaluations of sin may take. However, the collection of works, especially the more contemporary pieces, do not shy away from reflecting our gaze back at ourselves, forcing us to ponder what part we might play in the odyssey of sin.

Sin is temporarily closed. Keep an eye on the National Gallery website for details of its reopening.

Featured image: Diego Velázquez, The Immaculate Conception, 1618. Oil on canvas. 135 x 102 cm. Image courtesy of the National Gallery.