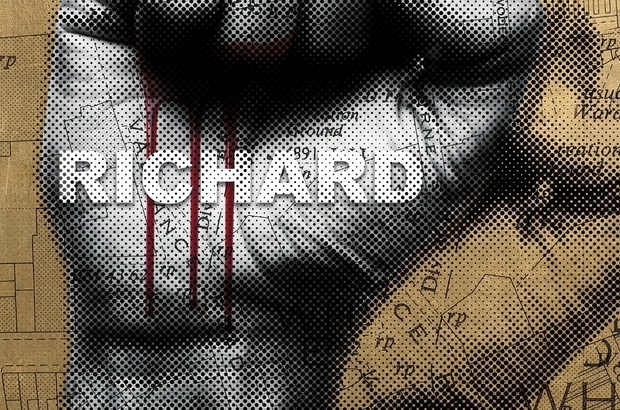

RÓISÍN TAPPONI reviews Richard III at the Barons Court Theatre.

Descend the rickety stairs of The Curtains Up pub into the belly of the theatre, and a rush of noise hits you hard – the drone of electric guitar; cymbals; organ. Down into the depths and bursting into the intimate space of The Barons Court Theatre, walking on the taped edges of a stage with a makeshift bar, more roughshod than the rather middle-class one upstairs. Lit by dim violet and stared down by a brooding Bacall pinned on the wall, the smell of beer staling the air.

In this reimagining, the title character Richard has his job split in two. Director Matthew Turbett is keen to evoke the similarly illustrious tale of the Krays, twin brothers and gang leaders in 1960s East London. Turbett reinvents the play to highlight the pervading trope of the male-dominated political power struggle. The ‘main’ Richard (Duncan Mitchell) embodies your cheeky, arrogant, East End boy, with a tight comb-over and a mildly ill-tailored suit that moves him about, setting the pace of the play. The ‘other’ Richard (Samuel Parkinson) marks his presence with heavy breathing, which, as is the case with Hopper in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, creates suspense. The silencing of this breathing will ultimately foreshadow all hell breaking loose. While Shakespeare undoubtedly had Machiavelli on his mind when writing Richard, this second Richard enacts a much more Mephistophelean role. He acts with jarring, violent intensity – he is always present, yet, apart from delivering the opening monologue, speaks very little. When he does speak he spits spoonfuls of bitterness, and is the only character to break the fourth wall and make direct eye contact with the audience, boorishly and actively gazing.

The other characters barely acknowledge the other Richard’s presence, and, as supported by his absence in the family portraits on the back wall, he is largely invisible. Always in close proximity, the twin brothers have a strange relationship, they rarely make eye contact but work the stage in sync as if the same person, their difference in composure the only pertinent characteristic setting them apart. When they do communicate, they literally finish each other’s sentences. The ‘other’ becomes a sort of ‘id’ for the dominant Richard, the devil-on-the-shoulder, the repressed, darker side constantly present in Richard’s life that he can’t, perhaps does not want to, shake off. The violence of the ‘other’ manifests in the combat scene between Richard and Richmond, a gang fight, balaclavas and all, representing the Battle of Bosworth Field. While Richard fights, his psyche animalistically crouches in the corner, mirroring his fist movements with a certain composure, illustrating how, by the curtain, Richard’s darker side has won bloody control and he in turn has descended into calamity.

Apart from the splitting of Richard’s personality, the production remains traditional. Minus the accents and the costumes there is little done to transpose the play. Exempting the dream scene, where the ‘other’ floats Kate-Bush-style around under a rosy wash to the echo of Richmond’s death threats, little is abstracted. The battle is on-stage combat and the murders are portrayed as realistically as possible. Yet there are certain enduring elements, primarily the themes of family, betrayal and manipulation, and the universality and timelessness of these enable the transposition of the script to our contemporary society.

As drawn out in King Edward’s (Cyril Blake) Don Corleone act, the particular theme brought to the forefront in this production is that of family drama, where there are strong family ties but little love thickening the blood. The tenuous relationships are artistically shown by characters who cling to the corners and edges of the stage, tip-toeing around the peripheries, trapped by the audience on three sides. Perhaps the strongest scene in the play is when Richard is blackmailing Queen Elizabeth into convincing her daughter to surrender to him. With Beatrice Lawrence as Elizabeth, the stand-out performer, there is an aggravating tension which was stark in the way Elizabeth and Richard animalistically circle the edges of the stage, only bursting forth physically when the script reaches its climax.

Undoubtedly, Matthew Turbett has done a bold job transposing the play to the underworld of ‘60s London. Splitting the personality of the eponymous Shakespearian villain is an admirable means of delving into Richard’s challengingly twisted psychology.

Pentire Street Productions’ Richard III will run at Baron’s Court Theatre until November 19th. Find tickets and more information here.

Featured image courtesy of Pentire Street Productions.