GENEVIEVE MORGAN explores our distorted perception of time in light of easing Covid restrictions, through the words of several notable writers.

Right now, with Covid restrictions easing, we are adapting back to the normal. This is the time that we have all been waiting for, the time that we have prayed to get to. We should rejoice at this moment of liberty! Of health! Of having our lives back! Of being back at university, having face-to-face teaching, being with friends, seeing family, hugging people!

Yet have we even noticed this shift? Not long ago, we could not leave our homes at our will, could not see the ones we loved… So what explains this lack of catharsis, at the point of reaching something that we’ve all been longing for? After long consideration, I think that this is not just a matter of pessimism in the human spirit, but actually an issue with how our consciousness organises time. It would seem that we live in constant pursuit of the future, thinking incessantly of ways to improve and increase certain things in life. This makes us neglect the present, and, seeing as the present is the only time we know, and will ever know, risks us wasting our lives entirely.

For me, the perpetual strive for the future is best represented in T. S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land (1922). The pursuit of the future renders the present barren: the present is not cultivated as a place to live in and enjoy. It is treated as a means to something else, a mere stepping stone, or something to ‘get through’. Yet this perpetual chase is a tragic, endless game, of trying to line up with your shadow when the sun is behind you. Your eyes are constantly fixed on the floor, concentrated on achieving and imagining what the future will be like, when the only thing that is certain is the here and now.

The Waste Land’s representation of technological advancements in the modern world paints the present as a desolate land of meaninglessness, where the purpose of life is the future. Working at a bank in London when he wrote the poem, Eliot was immersed in a society dedicated to building a modern, more efficient world – building something better. Yet the cost of ‘building a future’ is, of course, the erosion of appreciation for the present. If the present is the only time we really ever know, then dedicating ourselves to future endeavours will leave our lives empty and wasted. This manifests itself in the image of the ‘crowd… over London Bridge’, where ‘each man fixed his eyes before his feet’. The depressing tendency to walk over the world-renowned London Bridge, focussing on the moving of feet and not the view, does not just fit into the metaphor of chasing a shadow, but suggests that the focus is on the need to keep moving, because being static would cause chaos.

Franz Kafka’s short story Poseideon (1920) exemplifies this silently self-destructive way of living, where routine behaviour and waiting for the future cause a barren existence, and prove to be more devastating than death itself. The idea of ‘saving life for later’ is analysed through Albert Camus’ absurdism – arguing that we don’t live in the present because we’d be unable to make sense of it. To get over this, we cling to memories of the past and ideas of the future, and our present becomes a collage of these constructed images. Through this, we attempt to control our lives, rather than allowing life to simply happen to us. While this might be an appealing coping mechanism in times of hardship, it effects no differently to a slow poison.

For Eliot, striving for the future make us slaves to time, because the future is not something we will enjoy for ourselves. Since we only exist in the present, the future belongs to future generations. In fact, in The Waste Land, he calls the modern labourer a ‘human engine’, like a ‘taxi’: he is stripped of individual identity, existing only to perform for others.

Like Camus, Fyodor Dostoevsky observed that we consciously prevent ourselves from living in the present because we love the process of doing, but achieving makes us feel empty. In other words, humans feel worth only when they feel useful, and so experiencing the effects of work is not actually fulfilling. He wrote in Notes from the Underground (1864) that ‘perhaps the whole aim after which man strives on this earth consists simply in this uninterrupted process of achievement’. This ‘formula’, he says, is ‘no longer life… but the onset of death’. Like ‘a chess-player’ who ‘loves the process of the game, not the end of it, man is afraid of attaining his object and completing the edifice he is constructing’. Through this paradox of building something not to enjoy it but simply for the sake of building, Dostoevsky criticises humanity for its need to be distracted from the process of simply living, and thus its inability to feel emotionally the fruits of life. This notion of blind existence is built on by Andrey Tarkovsky, in a chapter of his book Sculpting in Time (1985). He writes that time and memory are merged together like ‘two sides of a medal’. One cannot exist without the other: the present, of course, exists, but ‘it slips and vanishes like sand between the fingers, acquiring material weight only in its recollection’.

Are we afraid of the present? Are we too afraid to comprehend that life might just be as it is? If the present is certain, do we distance ourselves from it because the truth might be too overwhelming? The past and future are but distractions and preventions from authentic living. The result is that often, we can’t feel the effects of what we’ve worked for, and experience proper joy. As pessimistic as this might seem, it actually explains the problems with a mentality so far removed from life in the present. The only thing that’s certain is that we are alive right now, so we shouldn’t live elsewhere. This is a time that we have all hoped for, so we should live in it for what it is.

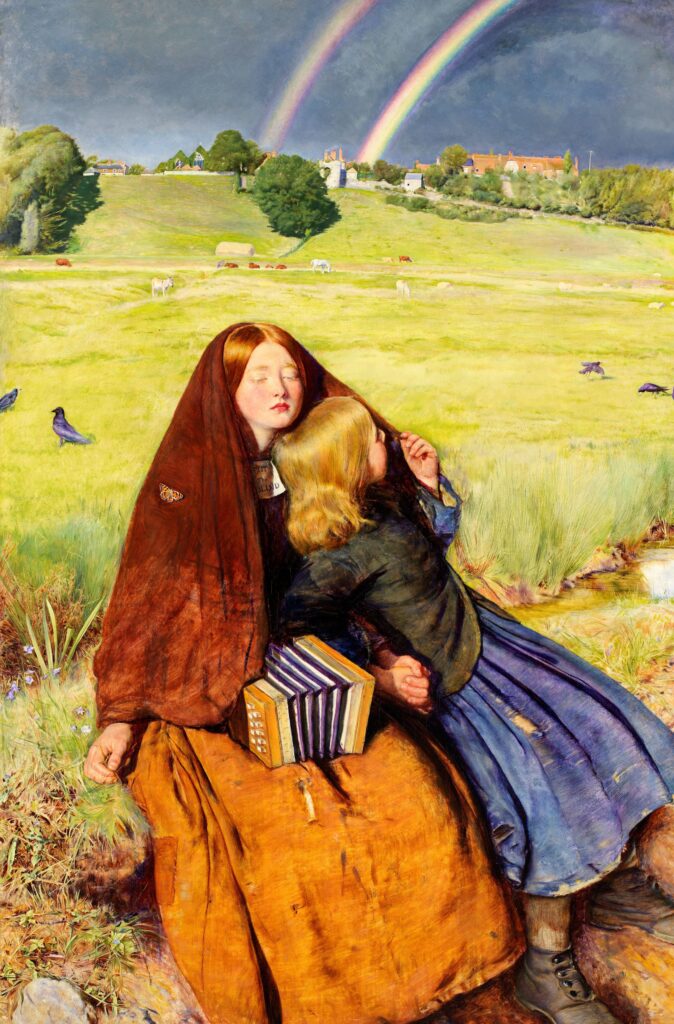

Featured image courtesy of Genevieve Morgan.