TANYA DUDNIKOVA: Lee Jan-ho’s film interweaves numerous narrative strands to convey the displacement caused by the Korean War.

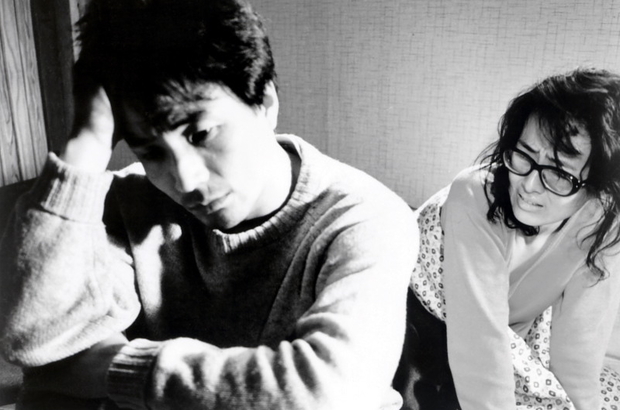

An isolated widower travels to the eastern coast of Korea carrying the ashes of his deceased wife, hoping to scatter them in a place closer to her hometown. Along his journey, he becomes burdened with the deaths of two more women who cross his path. Meanwhile, a nurse is escorting the dying chairman of a business conglomerate to his hometown. Pursued by henchmen of the chairman’s son, a politician who wants to keep his father’s journey from the press, the nurse stumbles across the widower with the metaphorical ‘three coffins’.

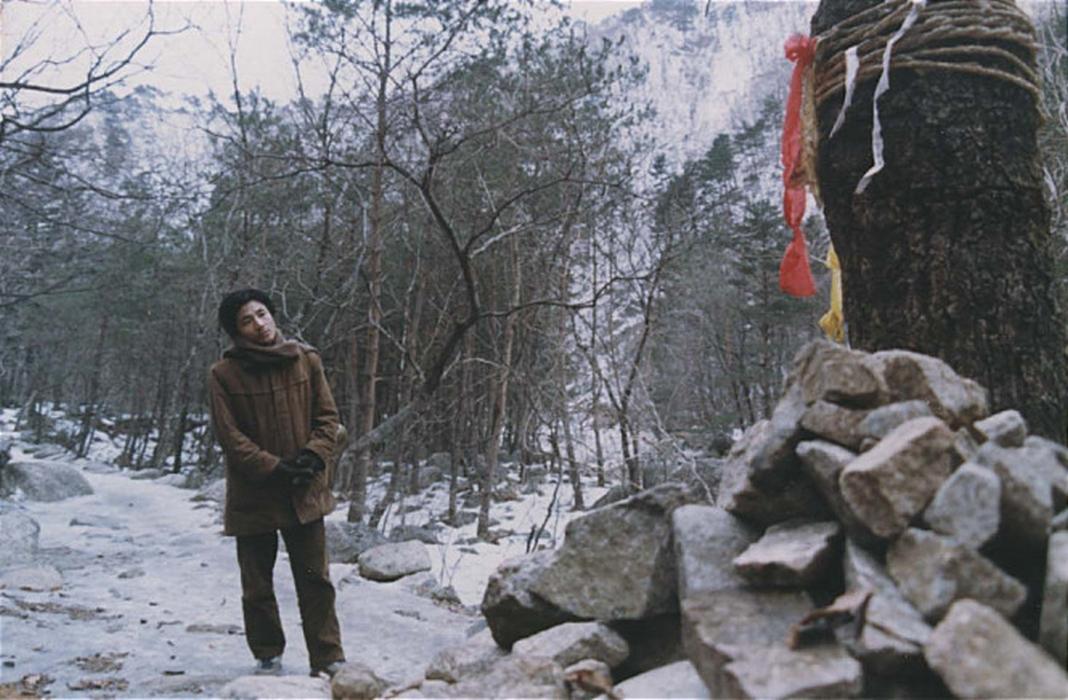

Despite facing much oppression under Chung Doo-hwan’s administration throughout the 80s, the Korean film industry was able to produce some outstanding pictures. One of the most enigmatic and evocative films of the period, The Man with Three Coffins is based on an award-winning novella by Lee Je-ha titled ‘Travelers Do Not Rest on the Road’. This experimental South Korean narrative feature, directed by Lee Jang-ho in 1987, is a meditative road film of sorts, but not one that provides much solace or a journey towards understanding. As one of the most prominent artists driving the renewal of the Korean cinema, a process which began in the 70s and reached full bloom in the Korean New Wave of the late 80s and 90s, Lee Jang Ho’s work is worth exploring for its pure mastery of aesthetics. The Man with Three Coffins is a stunning portrayal of suffering and loss, with a highly original use of colour and imagery.

The film’s message is open to interpretation; director Lee has mentioned in the past that he didn’t understand everything himself. Author Lee Je-ha approached the writing of his novella in a spontaneous, unthinking manner; as a result, the pieces do not all fit together logically. Lee Jang-ho took a similar approach to the film, focusing on conveying the story’s emotions above all else. He structures his film in fragmented, overlapping segments that feels more like a flood of recollections than a story with a beginning, middle and end.

Interweaving numerous narrative strands and oscillating between the past and present, this allegorical parable is not always easy to understand, particularly for viewers with a limited knowledge of South Korean culture and religion. Hard as it may be to follow Three Coffins, it is even more difficult not to get swept up in the film’s artistry. When Lee was a child living in Seoul in the years after the Korean War, the streets were always filled with broken glass; he and his friends would hold pieces of coloured glass over their eyes to see the world differently. Inspired by the sepia tone of old war newsreels, the monochrome palette of Claude Lelouch’s Un homme et une femme (1966), and Lee Je-ha’s allusions in an ochre yellow, Lee Jang-ho went to great lengths to create the striking tints the screen displays. The effect adds an aura of nostalgia to the film, but also works on an aesthetic level. Coupled with the film’s gorgeous compositions and location photography, Three Coffins offers so much beauty to behold. The film is exceptionally cinematic, particularly in its cathartic final minutes when a shaman’s boat crosses a misty lake, which ranks as some of the most beautiful images ever created in Korean cinema.

The film’s meditative nature allows the director to convey various themes, most prominent being the displacement caused by the Korean War. The idea of a land divided in two, with its inhabitants unable to return to the place of their origin, is expressed through several of the storylines. In a Korea that suffered an unshakeable division, it was impossible to return home after the war. Entire families were, and still are, separated. Notions of reincarnation and fate, strongly associated with Korean shamanism, also exert a strong hold on the characters, which accounts for the striking and sometimes frightening imagery related to shamanism that consistently appears throughout the film. In a surreal gesture, it is repeatedly suggested that the nurse is a reincarnation of the dead wife, and thus by consummating his physical relationship with her, the protagonist achieves his goal of ‘returning home’.

‘The Man with Three Coffins’ was screened as part of the London Korean Film Festival, 2016.

Feature image courtesy of mubi.com.