EMILY DRIVER interviews Jane Clarke, shortlisted for the 2023 T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry, and Jason Allen-Paisant, the winner of the prize.

There are poet’s poets, and then there are poet’s poet prizes—that being the T.S. Eliot Prize. Described by former poet laureate Sir Andrew Motion as ‘the prize poets most want to win’, previous recipients have come to be known as the powerhouses of the poetry of today—Ocean Vuong, Seamus Heaney, Carol Anne Duffy, Ted Hughes—the list goes on. For the 2023 prize, the judges whittled down the submissions to ten dazzling and dizzying collections and presented the award on Monday, the 15th of January, to Jason Allen-Paisant for Self-Portrait of Othello. Before this announcement, I got the chance to talk to Jason and his fellow shortlisted poet, Jane Clarke, about the making of their collections and the strange and wonderful craft that is poetry.

Jane’s A Change in the Air is her third collection of poetry, composed of six polished sequences that navigate both past and present rural Irish life. Jane’s poetic vision falls like a lighthouse stroke on quiet moments of love, strength and community, succeeding, as John Berger’s Monet aspired, ‘to paint things not in themselves but as the air that touched them’. Jane writes with such confidence and naturalness on the poetry woven into the rhythms of everyday experience that you would assume she’s been writing all of her life. Surprisingly, this is not the case. Jane’s first collection, The River, was published in 2015 when she was 54 after she’d started writing poetry in her forties. Asking her about this relatively late start to her career, Jane told me that she had always dreamed of writing; however, after completing her English degree at Trinity College Dublin, she instead chose to devote herself to a life lived ‘in service of others as a psychotherapist and community worker’. Subsequently, she began psychoanalytic training in her thirties, which, she said, liberated something in her. She then began experimenting with writing and, through taking a course, found poetry to be the medium that best courted her creativity. It was through writing weekly and sharing her poems that Jane began to see the ways in which poetry, too, could be a form of service to others.

Since 2015, Clarke has already cemented her status as a celebrated Irish poet, winning the Hennessy Literary Award for Emerging Poetry in 2016 and the inaugural Listowel Writers’ Week Poem of the Year Award. A Change in the Air showcases some of Jane’s growth as she holds up a lantern higher, beyond contemporary experience and reaches out to illuminate corners of the past. The twin poems, ‘In the dug out’ and ‘When this is all over’, for example, attend to the hopes and fears of soldiers fighting in World War One, with the latter including a footnote sent by one volunteer, Albert Auerbach, to his sister from the trenches. Jane told me how the Auerbach letters had been a project she had initially been apprehensive about getting involved in, unsure if she would be able to translate historical artefact into poetic material. The key, Jane explained, was finding ‘the personal within the history’. Jane looked for little details and minutiae within the letters, such as a piece of heather that Albert had thanked his sister for sending him, from which she could begin taking imaginative liberties with. She said such images as the heather emerged to her as latent with so much unexplored depth and potential – like a piece of yarn she was then able to unravel in poetry. These details acquire their evocative energy not only in the ways in which they condense the ‘spirit’ of a person, place or feeling (one of Jane’s foremost concerns in writing), but also, by eliciting access to personal and private moments they also open up to a historical and universal experience. Such continuity is a keynote of Jane’s poetics—every bereavement, every wedding bell and every personal war history is part suspended, part swept up in the ceaseless flow of the river and time itself.

But the river of time can also be a threatening force in Jane’s collection. The achingly attentive opening sequence of A Change in the Air depicts memory as a vulnerable and fragile quality of life, gradually being eroded in submissions to dementia. Yet, at the same time, she also highlights its endurance as it is passed along through relationships and down family lines. I was curious to ask whether Jane thought of her poetry as a preservation of memory, a fight against forgetfulness of sorts. Reflecting on her first collection, The River, which revolves around the farm where Jane grew up and the stories that her parents used to tell her, Jane agreed with my evaluation, telling me that these things do feel precious to her and her writing of poetry is partly animated by her compulsion to capture and keep things. ‘Writing’, she said, ‘helps me remember more’, and often she finds memories lodged in the back of her mind, ‘like when your jumper gets snagged on something. Sometimes you can’t work out why they are there, but writing can help you remember and work it out’. She went on to discuss how, as well as being a way of commemorating, recording and perceiving one’s own experiences, on the other side of the coin, reading other people’s poetry can also help awaken memories of your own. Never inert nor static, Jane’s memories are active, illuminating energies which can be struck upon like an instrument and made to sing in poetry.

The poems that make up A Change in the Air manage to crystallise entire galaxies of feeling into short lyrics, even within singular lines, as if each word has been weighed by hand for value. As well as conveying universal experiences, Jane’s poetics is one that is also thoroughly Irish in tenor and deeply invested in the depiction of Irish life. At the moment, Ireland seems to be having a sort of renaissance-level boom in the arts, with Irish writers dominating the awards for both poetry and fiction. I asked Jane about this effervescent Irish literary scene and attempted to probe the secrets of their success. ‘You know that old saying, it takes a village to raise a child’, Jane laughed, ‘well it takes a community to make a writer’. Jane lauded these artistic communities in Ireland where everyone encourages each other and where artists are motivated and energised in their pursuits every time someone ‘lifts their above the parapet’. On top of this, Jane told me that writers receive excellent support from their arts council and have lots of journals, festivals and pub readings where they can test out their material. The significance of the artist is also recognised beyond the communities they work in; Jane said that artists are often called in to respond to social events, which, she suggests, shows a level of respect for the arts as able to convey something that politics and other discourses cannot: ‘Writers need encouragement. They need to know that their work matters and that’s in the atmosphere there.’

The tour-de-force global sprawl of Jason Allen-Paisant’s award-winning collection, Self-Portrait of Othello, is quite a far reach from the languid, slow-motion rural life depicted in Jane’s A Change in the Air. In this electric and trailblazing collection, Jason takes one of Shakespeare’s most notorious and elusive tragic heroes and the gaps in his story as vehicles for examining black male bodies in Europe through time, interweaving questions of aspiration, masculinity and immigration into a rich poetic narrative of a search for belonging.

Jason’s collection is anchored in a striking premise: invested in the project of filling in the ambiguities of his character and of, as the title of one of his poems puts it, ‘What Shakespeare did not write about’. I was eager to ask Jason how the idea for this project came about. Jason explained to me that he had always felt unsatisfied with Othello as a play but especially with the critical approach that has congealed around it:

‘Very often, people want to talk about the mental decline, the obsession, the jealousy—how does a person come to murder the person he loves? It becomes a question of psychology. But this approach obscures a lot of relevant questions.’

Readers of Othello, Jason posits, ‘haven’t really begun to ask who Othello is and what’s driving him, what’s making him tick. We need to dwell in the fiction’. Jaon contends that Othello hasn’t received the same type of critical attention that other characters have been given, and this prompted him to reflect on ‘how would I go about imagining an Othello I knew more about’. Jason was eager to put on record that he thinks Othello is an important play and that he hails Shakespeare for making a Moor a tragic hero, but questions remain to be answered and explored—as one of his poems puts it, ‘I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story’. Jason explained that the ‘Moorish’ ethnicity of Shakespeare’s hero represents a whole body of people present in Europe since the Crusades and the war against Islam, and his collection was prompted by the question of ‘how do we account for these people who were so interwoven into Europe’s fabric’ and, equally, keep one foot on the world today, where such types of culture wars are very much still ongoing.

My interest was piqued by the way in which Jason understood the genesis of his work as born out of and positioned against the critical tradition surrounding the play, and I asked him whether he considered his collection as a surrogate form of criticism. Jason told me that he had been influenced by Anne Carson’s The Glass Essay in which poetry itself becomes a form of literary criticism. However, where traditionally, the critical method is stopped in its tracks, poetry can work by ‘allusion and elusiveness’, braiding together different ideas. The critical attitude is an important element in his collection; poems such as ‘The Picture and the Frame’ incorporate the discourse of art criticism satirically in essayistic, prose-like lines, placing it under pressure. In contrast to the rather stale mode of academic discourse, poetry, Jason said, has ‘more freedom, more freedom for things to come together in alchemy’.

Clearly, Self-Portrait of Othello is propped up by Jason’s extensive research of both the play and the historical conditions out of which it was born. This creative approach differs markedly from that of Jason’s previous collection, Thinking with Trees, which was largely composed on the move outside during lockdown walks, documenting and detailing Jason’s experience as a black body in green spaces. While continuing his thematic interest in, as Jason put it, ‘how we see, what our training allows us to see and not see’, he said that the methodology pushed him into a completely novel type of creative process. It included doing a lot of things that he wouldn’t usually associate with the poet: reading a lot of scholarship, scouring JSTOR articles and finding books about travellers to Venice in the Renaissance era—‘I needed to feel I knew what I was talking about. If I’m going to speculate and fancy, it’s going to be on the basis of facts’. He explained that a lot of the work was more akin to that of writing a novel, ‘your character is being conjured in your mind but not out of nothing. I wanted to get the parameters of what’s possible right’. He also reflected upon how a lot of this research demanded him to move out of his comfort zone, scared of what he might discover and where it might lead. The material itself, he explained, was triggering and difficult, but the more he read, the more he saw connections and felt that there was more to be done in this area.

Jason also emphasised that there was a lot of fun to this project. Like his previous collection, Self-Portrait of Othello also entailed working within the spaces he was depicting in poetry. He visited Venice twice over the eight-year process of writing the book, so while some parts had to be composed at a remove from his subject, others are the product of his experiences within the landscape of his collection. For example, the ekphrastic passage on Veronese’s Feast at the Home of Levi was largely composed within an art museum in Venice. There is something valuable, Jason reflected, on writing in the presence of his subject: a ‘different energy is gained, especially when you’re seeing something for the first time.’

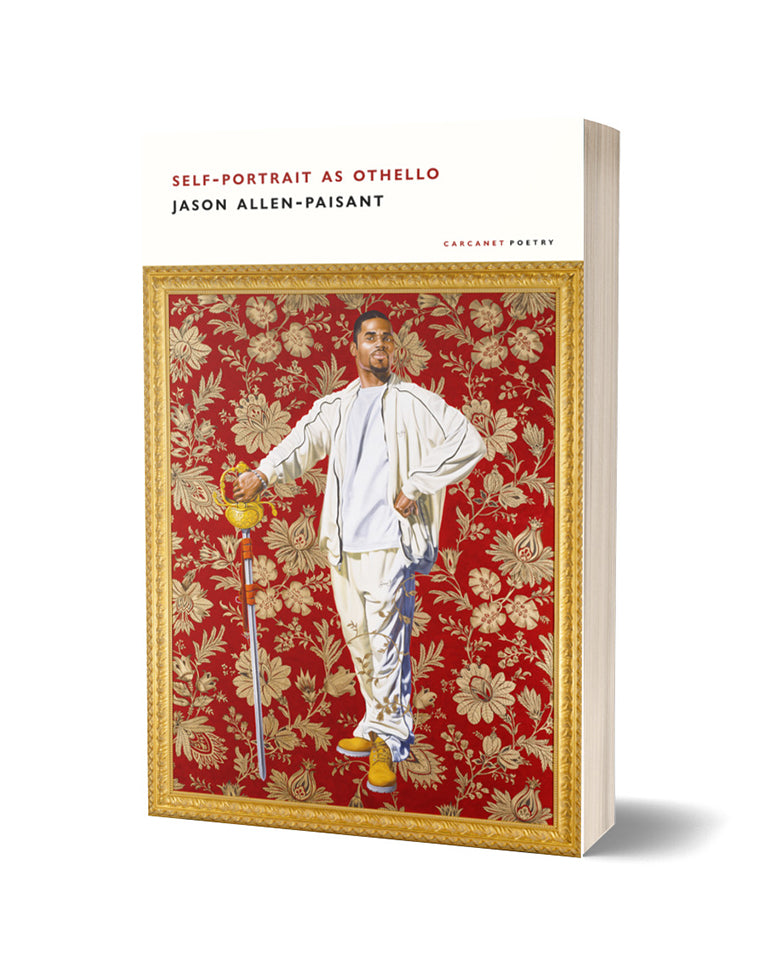

Anyone picking up Jason’s collection might agree with this observation, as its front cover is definitely an art to marvel at in and of itself. The cover, by Kahinde Wiley, pictures Jason standing in a regal posture against a red and gold wallpaper, holding a sword and dressed in a white tracksuit and timberlands in a subversive spin on a seventeenth-century Dutch portrait. The effect is to ‘play with the reader. Shock them, but not in a bad way, more in a provocative sense, jar expectations’. Putting a black man in an effectively white frame, Jason said, creates ‘an interruption in the viewing process’, paving the way for his interrogation of the black body across a rich tapestry of European spaces.

The way in which Jason’s Othello is able to metamorphose and adapt across multiple cultures, languages, and spaces becomes a cause for celebration in the collection. He told me that this fluidity, this ‘Joy, is an affirmation of a statement that yes, we are here. Ecstasy is needed in the face of violence and brutality, and we can relate to that today’. Shapeshifting, he explained, is ‘a strategy that black people in the diaspora have used to gain power; it means that they can’t be pinned down. It was important to create an Othello who revels in his heteroglossia’. Jason subsequently went on to reflect upon how this quality of multiplicity is also an integral aspect of his own experience having moved to England from Jamaica:

‘Sometimes, with instability, it can be scary because you feel that you’re never totally being yourself with any person. But there’s also a joy in it, not having to be pinned down. A lot of immigrants know what I’m talking about through body and through language. The person who comes into a different language space is somehow able to be at home in the host language as well as their home language. There is a joy in having a part of you that cannot be seen, that isn’t transparent if you can see it in that way. It becomes a secret sort of reservoir to draw on. That’s how I see it coming from rural Jamaica and going to Oxford, acquiring a camouflage. And there’s no end to the implications of that and that reality of being multiple, and it’s not chronicled a lot.’

In December 2022, The New York Times published an article under the title ‘Poetry Died 100 Years Ago This Month’, referring to the publication of T.S. Eliot’s epoch-defining poem, The Waste Land, which supposedly ‘kill[ed]’ poetry the same way that James Joyce’s Ulysses is said to have ‘broken’ the novel. Yet, 100 years on, Jane Clarke and Jason Allen-Paisant, as well as the other poets shortlisted for the 2023 prize under T.S. Eliot’s name, continue to inspire wonder, traverse new ground and send echoes scattering across new spaces. As Jason described it, poetry is a practice of alchemy—it is a chronicling of the ways in which matter evolves, transmutes and renews. In this, poetry is not ‘dead’, but an inexhaustible source of energy.

Featured image: Jason Allen-Paisant. Source: BBC.