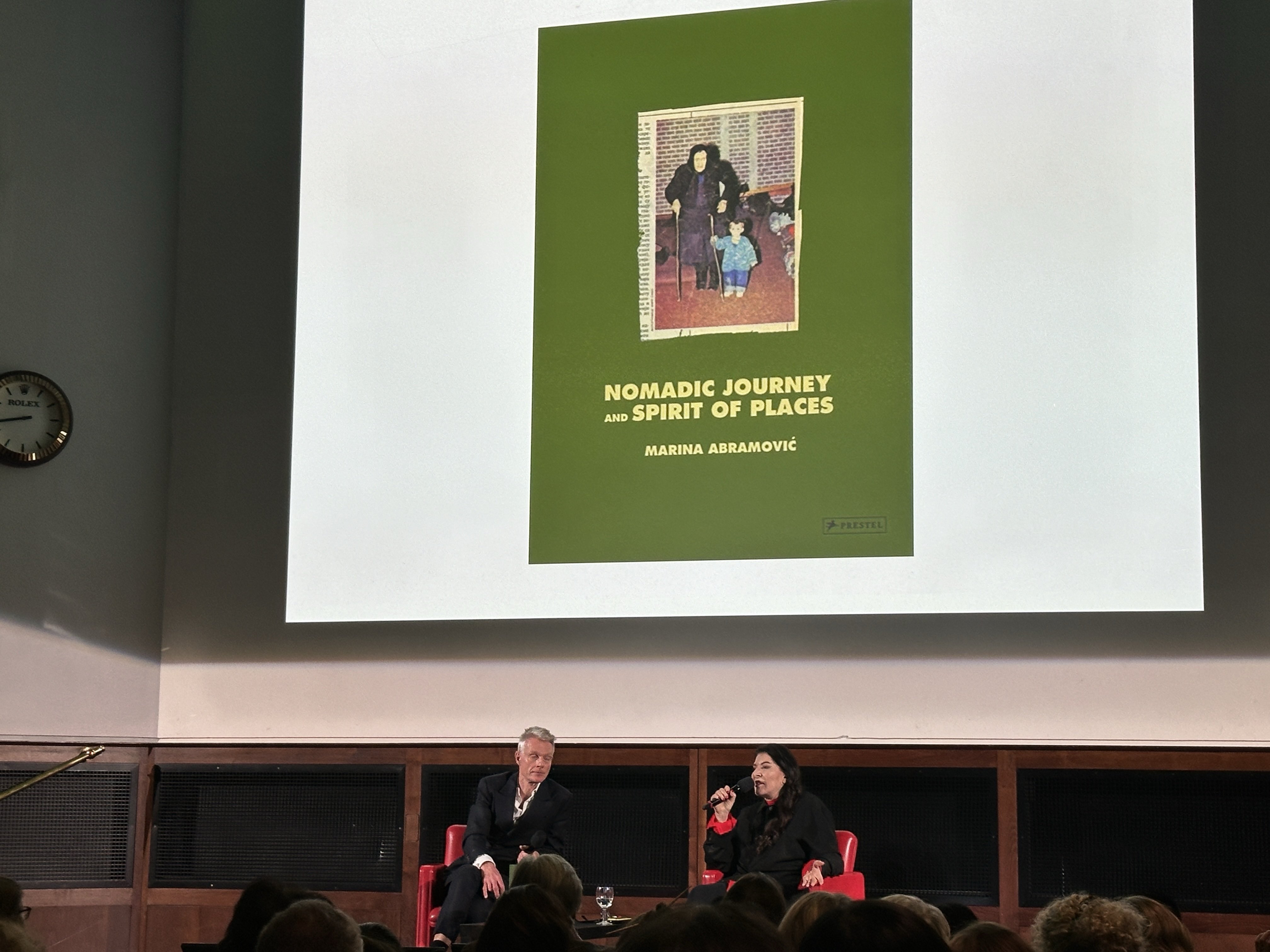

JULIA PANTIRU attends a talk with Marina Abramović celebrating the release of her new book, Nomadic Journey and Spirit of Places.

Marina Abramović resides in my phone: she is all over my Instagram, walking past posters of her exhibition. More jarringly, the app is also flooded with a simulated iMessage conversation in which the artist offers instructions on how best to prepare to visit her exhibition: no sex, meat, alcohol or drugs for three days; speak to few friends; attend without a watch or a phone, and just immerse in the experience… Despite this ‘required’ rigour, exhibition tickets are running low. Art-enthusiasts are clearly ready to visit extremes for Abramović, which only attests to her brilliance and lasting relevance. My fascination with the artist may explain her abundant presence in my online space; but it could also be a virtual expression of her current ubiquity on the cultural scene: recently, she has put on two exhibitions, Marina Abramović Institute Takeover and the Marina Abramović Retrospective, launched two books, presided over the opera 7 Deaths of Maria Callas, and even released a skincare line. Clearly, the artist is on a self-professed mission to expand her audiences to younger generations who might not have experienced her iconic previous art.

Yet Abramović is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere to be found: despite this activity, she is no longer performing her exhibition pieces, as she once so famously would, but has instead entrusted them to her disciples: the students of her institute. A recreation of The House with the Ocean View (2002), for instance, in which the artist spent 12 days and nights inhabiting three rudimentary gallery rooms, is now being recreated by student Kira O’Reilly. In conversation with Tim Marlow at the Royal Geographical Society, Abramović explained that an exhibition appearance would now be more disruptive than conducive—the phones pointing at her from the audience only confirmed this. She even joked about investing in a blonde wig just to be able to witness the re-interpreted performances. She further admitted that she was willing to cede ownership of her performances to allow the younger generation to take over them. The artist seems to have found new, more subtle ways of engaging audiences involving less direct interaction.

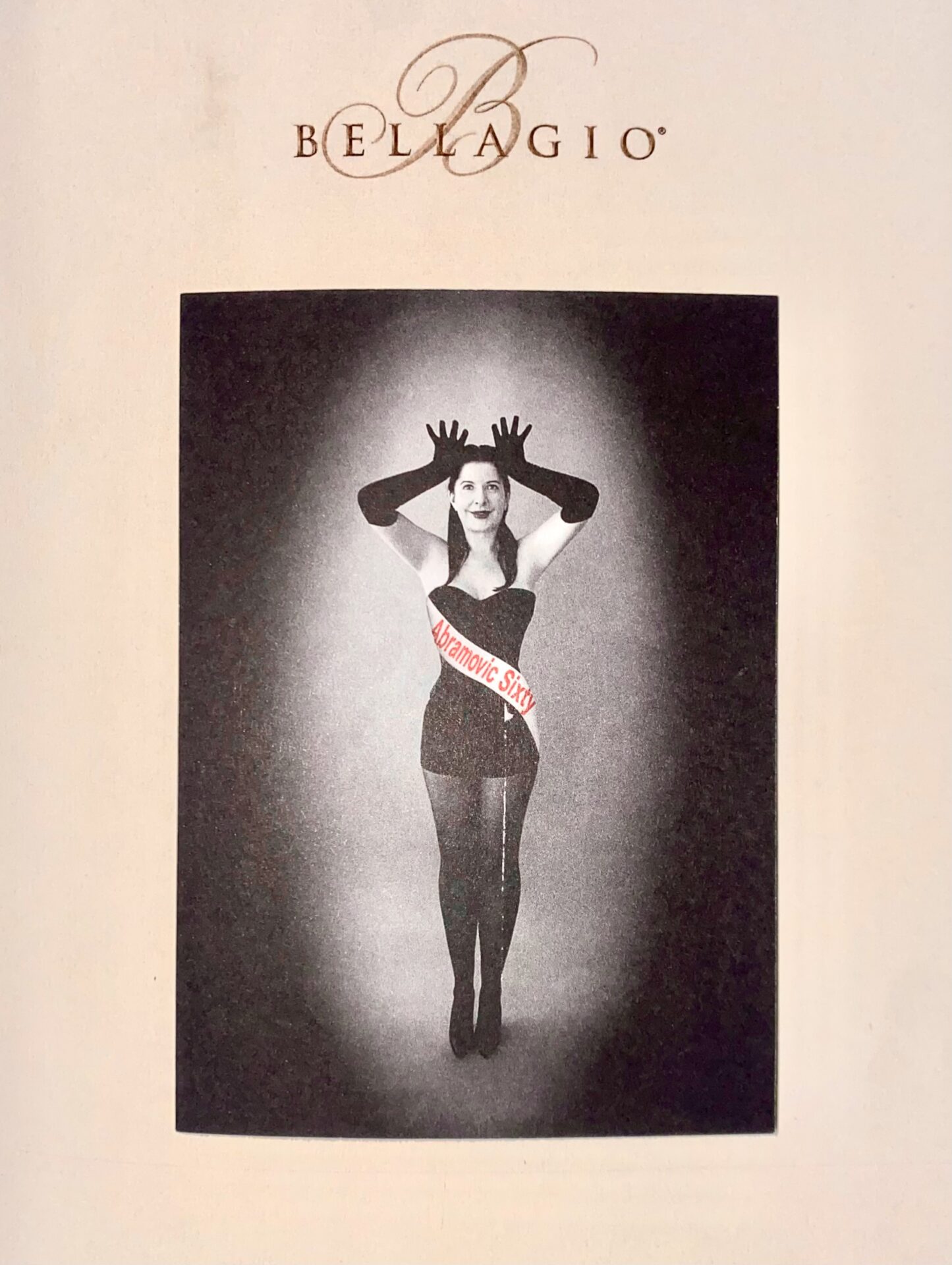

Nomadic Journey and Spirit of Places (2023) reaffirms this observation. Abramović calls it an ‘artist’s book’, an art form that utilises the book as a medium. Hers combines two personal collections, one of various hotel stationery collected throughout her travels over the years, and another of notes, poems, newspaper cut-outs, matchsticks, photographs, and drawings; the latter is then placed on the stationery. In the introduction she praises the liberation offered by the creative process undertaken: she assigned the aforementioned paraphernalia to random hotel stationery and arranged the resulting pieces using a ‘system of chance operations’, picking out the pages blindfolded and forcing herself to accept the result. This allowed her to discover a ‘freshness to flow’, and find a range of new meanings in her memorabilia. At the talk, Abramović revealed that when interacting with the book, one should close their eyes, open a random page, and force themselves to interact with whatever is presented to them…

The reader’s participation is thus equally facilitated and hindered by the author: her clearly dictated method of chance, chaotic and free, while denying us any informative commentary, engages the reader in a double ‘blinded’ process of decoding and trying to find ways to participate. I, personally, found points of convergence between myself and Marina in the life of the expat, particularly in her notion of the body as home, but also in her photographs from Yugoslavia, which could just as well be my family’s in Romania.

In conversation with Marlow, Abramović jokingly deviated from questions asked, and instead showed the lucky ones present how she interacts with random book pages. Some triggered personal memories, like the stationery from a hotel where she discovered a rat on the table after dinner. Others prompted her to think of figures she admires, such as a series of questions typed up in response to Carole Schneemann’s Naked Action Lecture (1968). On another page we find a picture of her with a bloody eye, a consequence, she explained, of ‘too much in-between’; bringing back a concept familiar to Abramović aficionados, the eye exhausted to the point of bleeding evidences a life spent in transitional spaces, such as airports or hotels, places where she believes destiny happens. This book is not just the result of such places, but perhaps a physical copy of that state of in-between too.

Later into the talk she also discussed some pressing socio-political issues, such as the wars in Ukraine and Palestine, which prompted her to discuss the difference between televised and aestheticised death, pointing out the hypocrisy in our experience of the two: we are entirely desensitised to human death presented on the news, but invariably moved to tears when presented with beautiful, tragic death on stage. Whilst there is no explicit reference to socio-political issues in the book, there are instances of historical significance that may elicit similar responses. Take for instance a sheet of paper from a hotel in Belgrade, matched with a yellowed note filled with handwritten names and phone numbers, which acts as the background for a newspaper cut-out announcing Tito’s death. On another paper from a 5-star Belgrade hotel, a picture of a downed U.S. plane juxtaposed with a photograph of Serbian women dancing on its wing.

These collages are the book’s great merit: by allowing the double depiction of the artist’s personal life and her engagement with politics and history, they push us to face broader ideas about the chaotic coexistence of the two. Marina Abramović’s book allows the reader to rewardingly interact with their personal lives and the machinations of the real world that every now and then do not make sense.

Featured image: Marina Abramović, 2012. Image courtesy of Manfred Werner.