MADDY MARTIN reviews Zoïa Skoropadenko’s “flash” Torso exhibition.

Zoïa Skoropadenko’s Torso exhibits under London Bridge’s Stock Exchange Rifle Club, a hidden location where visitors are required to buzz the gates in order to descend the steps into the shooting range. This long, brightly lit hall, hanging over the River Thames, makes for an unexpected but effective space to house Skoropadenko’s large scale paintings of octopi posing as the male torso. Even more unusually, the Monaco based artist is only exhibiting her work for three days, in what she calls a “flash exhibition”. The concept of the “flash exhibition” reflects the chaos of our modern quotidian and offers an immediate opportunity to view Skoropadenko’s works before she packs up and heads off to her next unusual location around the globe. “If people like what they see,” she comments “then next time I’ll come back for longer”.

This method is obviously effective as she tells me she is going back to France next week to stage an even larger show in the centre of Paris. These small tasters of her work around the world have allowed her series to pick up momentum. As well as making the trip to Tokyo in February, she has been invited to exhibit her work in a gothic protestant church elsewhere in Europe, much to her surprise. According to Skoropadenko, not everyone had greeted her work with such enthusiasm. During an exhibition in Strasbourg, people had complained that her Torso series was pornographic, erotic, and iconoclastic.

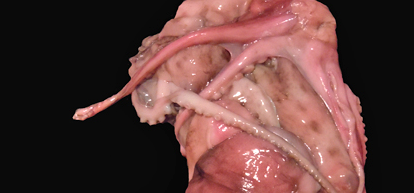

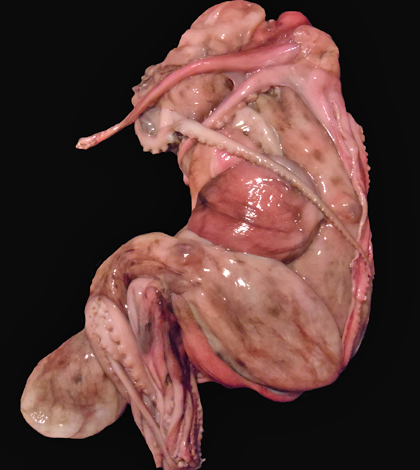

And in some ways, I agree. The paintings, which derive from the sculptures she had made out of octopi, have a sumptuous and sensual appeal to them, mainly due to the slippery nature of her chosen material, but also through the connotations of male torso in art history, especially regarding Greek and Roman sculpture. Skoropedenko presents the idea of ideal beauty and perfection in Ancient sculpture and subverts it through the use of modern media, presenting her work as at once grotesque and beautiful but accessible to a contemporary audience.

When asked about the importance of the torso in her work, the artist responded that it stemmed from acquiring octopi from a local fishmonger, who through the grape vine, had heard of a struggling artist in Monaco. The locals’ desire to “feed the artist” inspired her to do something creative with their offerings, instead of having them for dinner. Skoropadenko’s idea of the torso came from her desire to find a well known motif used repeatedly in art, and to turn it into a modern creation, to look back in order to look forward. The result of this combination of old and new is quite simply stunning and wholly effective.

In a world where so many contemporary artists strive for originality, to create something so abstract that it has simply ‘never been seen before’, it is quite refreshing to see an artist who embraces the past and transforms it into a completely new and original light in such a captivating manner. So, if you have missed Zoïa Skoropadenko this time around, I have no doubt she will be back on London soil again soon.