From Barcelona to London, ALYSSA NUNNINK reflects on Picasso’s body of work.

Yo no busco, encuentro (I don’t seek, I find)

I left central London for Spain last week like a consumptive Victorian maiden sent to convalesce by the seaside. In Barcelona, of course, I made a pilgrimage to the Museu Picasso. I’d gone before and been struck by the dedication reflected in his Pigeons series — nine iterations of the pigeons on his windowsill produced in six days, an attempt to circumvent creative block through restricting his subject matter to the immediate.

That was in the summer of 2022 when Picasso’s vibrant colour barely registered. I was used to it; it felt like my natural prerogative. This museum visit, though, bearing the pallor and haunted eyes that only a London winter can confer, I found myself floored by the sheer life blazing on the walls.

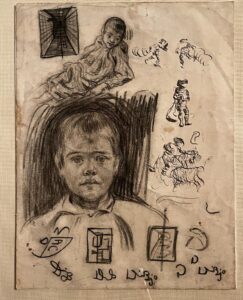

The museum presents Picasso’s work chronologically. If prolific output alone defined genius, his would be the clearest-cut case in the Western canon. He died with forty-five thousand unsold works in his house. I was going to title this piece Revisiting Picasso, but I doubt many of us can claim to have ever properly visited every corner of his oeuvre. I certainly can’t. In the very first room, I saw pieces I didn’t recall ever having seen before.

These were lattices of entangled lines and circles. Just lines and circles, but they reminded me of a neural network wired for cognitive flexibility, free association, play. Even pages of chicken-scratch French punctuated by expletives possessed an unlikely beauty. I wanted to blame the golden ratio or some other mathematical principle for imbuing these callous strokes with a harmony traditionally only afforded to the living. I knew, though, that if he had harnessed ratios, it was purely accidental. Is that something you can have a knack for — harnessing ratios with the flick of a wrist? I don’t know if there is a name for what he had a knack for.

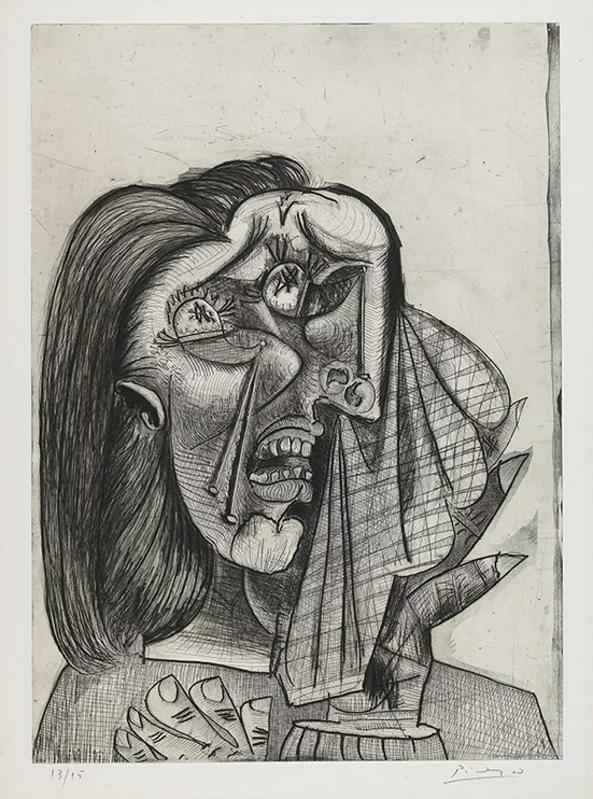

Reckoning with Picasso seems difficult. Hannah Gadsby’s New York exhibit ‘It’s Pablo-matic’ last year was a disastrous attempt to spin the legacy of modernism’s champion into the Twitter feed of a Lexapro’d-into-oblivion Jezebel writer. Her insightful commentary amounted to placards reading ‘Weird flex’ beside renowned prints. This severe lapse in judgement and taste from all parties involved indicates the extent to which Picasso’s abusive behaviour has poisoned contemporary perceptions of his art. His seductive cubist portraits of women cannot be invoked without mention of the bruises not depicted. It is said that he drove Dora, his ‘weeping woman’, to madness; in fact, she ended up in analysis with Lacan for two years. Perhaps Picasso was able to possess these women artistically precisely because he did so with so much force in reality.

I’ll set this matter aside, but this much is clear: he knew the body. He had both a gift and a talent in painting, but, I thought as his fifty-eight iterations of Las Meninas began to blur into one dark cubist chimera, he was a genius of the body. Jean Cocteau called him ‘a man and a woman deeply entwined… a living ménage’. His non-representational work has been described variously as pure, absolute (even the only absolute art), the precedent for the idea of the picture, and a defence of the unassailability of Dionysian life. The sacred and profane melt together. He made liberal use of the cryptic, mythical, and arcane, and was obsessed in particular with the Minotaur. There is much that evades understanding. These are the ‘more radical, disruptive, and disorienting aspects lurking within’ that Lisa Florman, Professor of History of Art at Ohio State University, contrasts with ‘the domesticated ‘Picasso’ to which we have become accustomed’ — whether this ‘domesticated ‘Picasso’’ is artistically nullified on the basis of moral error or merely reduced to cutesy cubist decor.

I felt roused by his work, and I felt this on a deep, instinctual level, which I frankly can’t say for much of the self-reflexive contemporary art that emerges from a niche of a niche of a niche like a branch of the Mandelbrot set. Picasso’s bodies and my own seemed to be in direct communion. My mind waited outside, attempting to piece together some sensible account from snippets overheard with a cup pressed to the door. Thought, symbol, signal, category, order, and reason, were all sidelined by the staggering preeminence of incarnation.

The gift shop sold little models of Picasso’s sculptures. I remember studying anatomy last year. What if our curriculum had covered not only the Vitruvian Man — the body as splayed on a clinical table for easy access, made thoroughly mundane by the fluorescent lights of medical rationality — but also the body in all its attitudes of agitation and chaos, as seen through the distortions of glass, mood, hypnagogia, dream? The body not as parts, as analytical substrates, as labelled diagrams, as Anki flashcards, as ‘systems’, as ‘specialities’, but as a whole transfigured by new forces every instant.

Back in London, I am working with a research colleague towards a collection of medical fiction. We have many things to figure out. One of these things, my colleague says, is the relationship, in these narratives, between genre and medicine.

“Genre?” I say.

“Expectation.” Of course. We expect that the gun mentioned on page 15 will become relevant on page 150. We expect that it all works out, or, if it doesn’t, if the cancer recurs right before the daughter’s wedding, if the treatment suddenly fails, the arc of happenstance is at least tragically beautiful, surpassing, for instance, the New Yorker’s threshold for ‘poignancy’.

Then my colleague and I talk about the ways in which medicine succumbs to the same fantasies. The progression of the discipline relies on researchers and laymen in equal measure suspending our disbelief that biology can be conquered in the ways we would really like to conquer it. We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

In central London, neat parallel veins branch off Tottenham Court Road like someone has combed them. Traffic’s red lights bead this vasculature late into the night. Empty white air hangs over the wide streets between skyscrapers. Billboard models pout or grin in uniform dissociation. City workers hurry through the drizzle in uniform black.

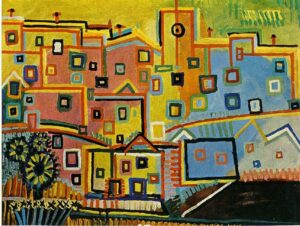

Under the influence of unprecedented quantities of vitamin D, I experienced Barcelona like Picasso’s cityscapes. Figures disappeared down darkly humid alleyways; alleys disappeared into nooks, hidden plazas, and buildings the colour of tangerine or grapefruit or honey. Half the cobbled streets were too narrow for cars. Apple Maps didn’t work. (Anecdotally, my phone subsequently stopped working entirely, so I was abandoned by every single crutch with which I typically navigate existence.) We divested ourselves of our coats and scarves. Sun drenched our bare arms. People danced in the park.

After gratuitously prolonged and unctuous afternoon tapas, my friend and I visited the Sagrada Familia. He expressed pride in our “aesthetically cohesive day”. This felt true, but why? On the surface, it made little sense. After all, Picasso’s work feels almost pagan. Gaudí’s architectural magnum opus is so deferent to God it is designed to stand one metre shorter than His nearest creation, Barcelona’s mountain. The Basilica’s Passion Façade represents the suffering, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. There is no shortage of hallowed tradition: it’s a Catholic masterpiece.

But standing inside that church, to me, has always felt like being inside an organ made of stone. Nude pillars branch like sinew toward the ceiling, which is densely populated by the folds of fungal growths. While we were there the sun began to set. The low light through the stained glass windows drenched every surface in reds and yellows — the flesh of the walls appeared alternately bloodied and jaundiced. The overall impression was vaguely sinister.

The eastern face, which became visible as we walked out into the dusk, is intentionally rough, almost confusing. It is said that this is to remind us of our own blindness to the power of God. If it is confusing, it is because we are not intended to understand. The longer you look, the more architectural features appear to quietly flout the canon, obeying instead their own internal logic. Gaudí did not see it necessary to give his angels wings.

In Spain, our own bodies eluded the layers that physically shield us from the misery of a London February. Picasso’s and Gaudí’s forms elude language, which critic Jerry Wasserman called ‘the psychic dress of civilised man’. I was humiliated by the fact that I don’t know a single word of Catalan (and don’t fare much better with Spanish), but I was also grateful for it. In some ways it felt like disburdenment. Granted, the Anglosphere is ever-widening, and so every one of Picasso’s works had an English placard, but I tried not to read them.

Life demands to be absorbed through every sense. Central London, however, can feel like an iPhone 15 set to grayscale. Walking around can feel like an infinite scroll. We are inundated with text, so much so that we are ourselves at risk of becoming black letters, homogeneous in accordance with a typographical standard, arranged in lines whose orderliness almost allows us to forget we are ultimately adrift in a sea of blankness.

When absolved of the symbols that otherwise intervene between sensation and response, we may get on with the business of being. Reacting and regenerating in equal measure.