DAISY GRAY looks at the state of music journalism today.

Meta, right?

Human beings love reproducing things in words: art critics describing art, poets saying that things are like other things, and music journalists transcribing sound into articles to help you understand it – and maybe even encourage you to listen to it. Shaping and influencing our opinions (or giving us something to furiously disagree with), music criticism satisfies a need for perspective, bridging the gap between casual listeners and music professionals. Simply put, we do – and hopefully always will – crave this kind of content, but the world that produces it needs to do more to stay relevant.

Music journalism has undoubtedly seen a steady decline. We lost the giant Q Magazine earlier this year, a casualty majorly symptomatic of the state of music journalism in 2020. The general turn towards digital has completely changed the landscape of most things; music most of all, somewhat devolving from the ‘prime’ your parents might call the age of records, print magazines, and Tab soda. Consider 90s kings NME: after ceasing printing a couple years ago, they have been reduced to a BuzzFeed-style writing model, writing ‘Top 100s’ of favourite artists and bands in a desperate plea for clicks. The content of the pieces themselves are not necessarily the issue – Rolling Stone still produces excellent reviews and features, for example – but the way we consume this media has meant that simple reviews and features are not enough anymore.

Reviews themselves are not what they used to be. Pitchfork stole the music world’s attention for a day or two, after rating Fiona Apple’s surprise new album Fetch the Bolt Cutters a rare 10. That big number seemed to be all that mattered, rather than the words themselves. Even the written word has lost some of its potency. The New York Times recently published a piece on Anthony Fantano as ‘the only music critic who matters (if you’re under 25)’, and it is honestly hard to disagree with. His reviews on YouTube produce Twitter storms of angry fans, seething because he might rate a Kanye West album as anything less than a 10. I have often argued with friends, who use his ratings as gospel to cement their view of an album. Numbers are great, but for a review, they are not overly insightful – and yet, increasingly so, they seem to be everything.

To be slightly cynical for a moment, this reliance on numbers indicates a slow downward spiral towards reductive journalism. To be more optimistic, at least it means it still has a place in the fore of readers’ minds. NME’s growing ‘Top 100’ model does not mean the end of days, but it raises the important question of what music journalism is and what it should be. In this age of technology, attention is king – and numbers are a quick fix. No one gets any points for pointing this out, but there are big winners and big losers. When reviews are based entirely around digits – or even when they are not – they tend to steal our attention quite quickly, but that attention does not always last long; worse still, small numbers can ruin your opinion of an album before you even listen to it.

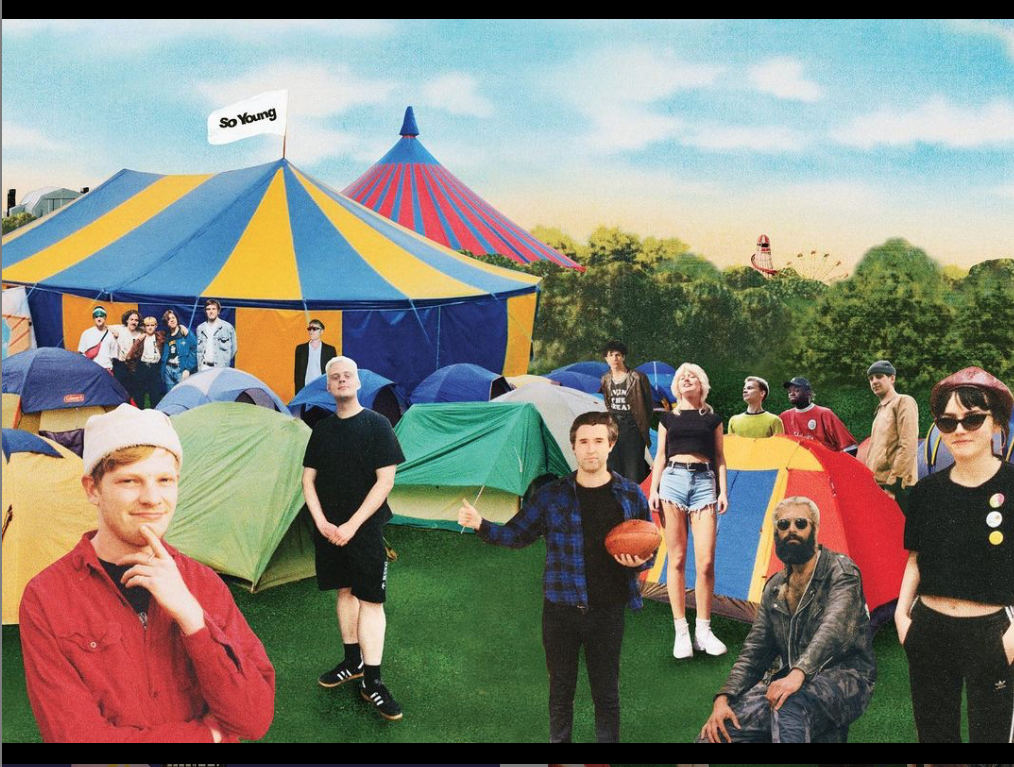

Success in music journalism has become increasingly more volatile, relying ever more on offers of more than just writing about music. Local journals, offering a bit of community spirit and (in better times) putting on small gigs to support local bands, seem to be winning the media war – but not by much. My hometown-heroes So Young spring to mind, who regularly sell out their art-filled music magazines and collaborative t-shirts, and work with local venues and record-stores to actually work for the music scene, rather than observe from afar. Frankly, they offer a glimmer of hope that music journalism has a good future. However, bigger magazines and platforms struggle to offer the same kind of appeal, and lack the luxury of the personal touch. In days gone by, NME were the coolest cats around, but that grungy, magnetic lustre they once had has nearly withered away completely.

Much like when I was a teenager, ripping pages out of a Kerrang! to stick on my wall, physical magazines still do have an important place, least of all in our hearts. Even here at SAVAGE, we pride ourselves on our physical journal, both aesthetically and content-wise – but online platforms are still essential; Q Magazine learnt this the hard way. One could say, Good!, it is better for the trees. Digital is the future after all, but surely there is room for both, right? Either way, it sits in the palm of your hand, on paper or phone; neither is intrinsically better, but to lose magazines would be an irrevocable loss for many.

The music world knows very well that physical ain’t dead, as vinyl and even cassettes have seen a boom – and it is not even a case of style over substance. London-based Sad Club Records are a label that produces everything on cassette (as well as digitally); although small, they show signs of the real heart of the music industry. Aesthetic is one of music’s best friends, regardless of genre. Niche might not sell big, but it sells.

It is no secret that journalism and magazines have had to evolve exponentially with the growth of social media. Some have followed the patterns of the internet’s big players, but the most interesting – and, importantly, readable – publications do more than just write about music. Physical media may not be what it was – for better, or for worse – but it has by no means lost all relevancy. Certainly, in a world dominated by corporate news, we should cherish smaller, independent publications, and those that really provide insightful, informed music journalism. Whether Will Gompertz or Fantano, I like to think that proper criticism and voices of comparative reason will always be relevant.

Feature image courtesy of BBC.co.uk.