CHANTAL GOULDER is a multimedia artist going into her second year at Slade. Her work explores themes of identity, cultural heritage and the environment. RUBY ANDERSON interviewed her about how her practice has been affected by lockdown.

What kind of things had you been making before lockdown started?

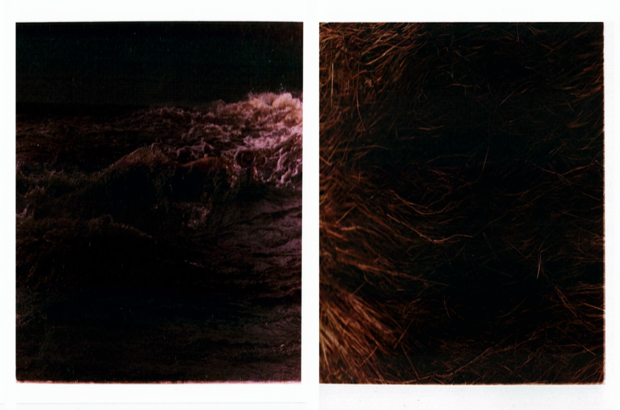

Before everything cut off, I was doing a big mixture of stuff. I wasn’t focused on one specific medium; things just took their form naturally. At the end of second term, I had started doing a bit more work in the dark room, learning how to enlarge and print from colour negatives. It was really fun – I had a lot of time to experiment.

So would you say you were focusing more on exploring mediums than themes this year?

Whatever I am making, it is always centred around the key themes of my practice. Most of the work I make is concerned with narrative, be that personal narratives based upon memory and personal history, or things that I’ve researched like folklore and the specific histories of local areas. In January, I presented a video piece to my seminar group that I based around a lost family object. The discussion that came up as a result of that was about how objects can be vessels for memory or history, and how they can become a source of information. The piece was accompanied by audio also, which was quite melodic and rhythmic, so there was a discussion raised about music in art as well. Since then I have been thinking about the role of music in my practice and whether or not the two are separate.

As your work is about narrative, to what extent do you create something with the viewer in mind?

Because of the work that I like to make, I think it is important that I keep in mind how people are going to read it. I often research and use figures or motifs that have their origins in folklore and visual culture. I’m intrigued by the fact that these motifs contain their own narrative, but then viewers can cast their own narratives onto them as well. The crossover between personal interpretation or projected narrative and actual meaning is interesting to me.

It’s really interesting to consider the extent to which viewers subvert narratives to meet their own expectations or desires. What type of things have you been making more recently?

I don’t know if it’s being back at home in the countryside, but recently I’ve been making work about rural landscapes and art’s interest in the pastoral. I am interested in how, throughout history, artists have romanticised rural life.

To what extent do you think that a knowledge of art historical traditions, such as the romanticising of pastoral imagery, is important in aiding the understanding of works?

I think art history is interesting, and it really helps contextualise your work. However, I’m hesitant to say that you need an understanding of it. The art world is elitist, and the idea that you have to have an academic understanding of art to have a connection to it alienates a lot of people.

I agree. That assumption can be very limiting.

It makes people think they can’t understand art, when everyone can, it’s just you can be taught to read further into it, to relate it to history, to theorise it in a wider sense and to look into the implications of it. To me, it’s importance definitely depends on what kind of work you’re making. The allegorical imagery of the shepherdess, for example, which is what I’m looking at at the minute, has come about through research as opposed to being rooted in art historical understanding.

How do you go about conducting research for your pieces?

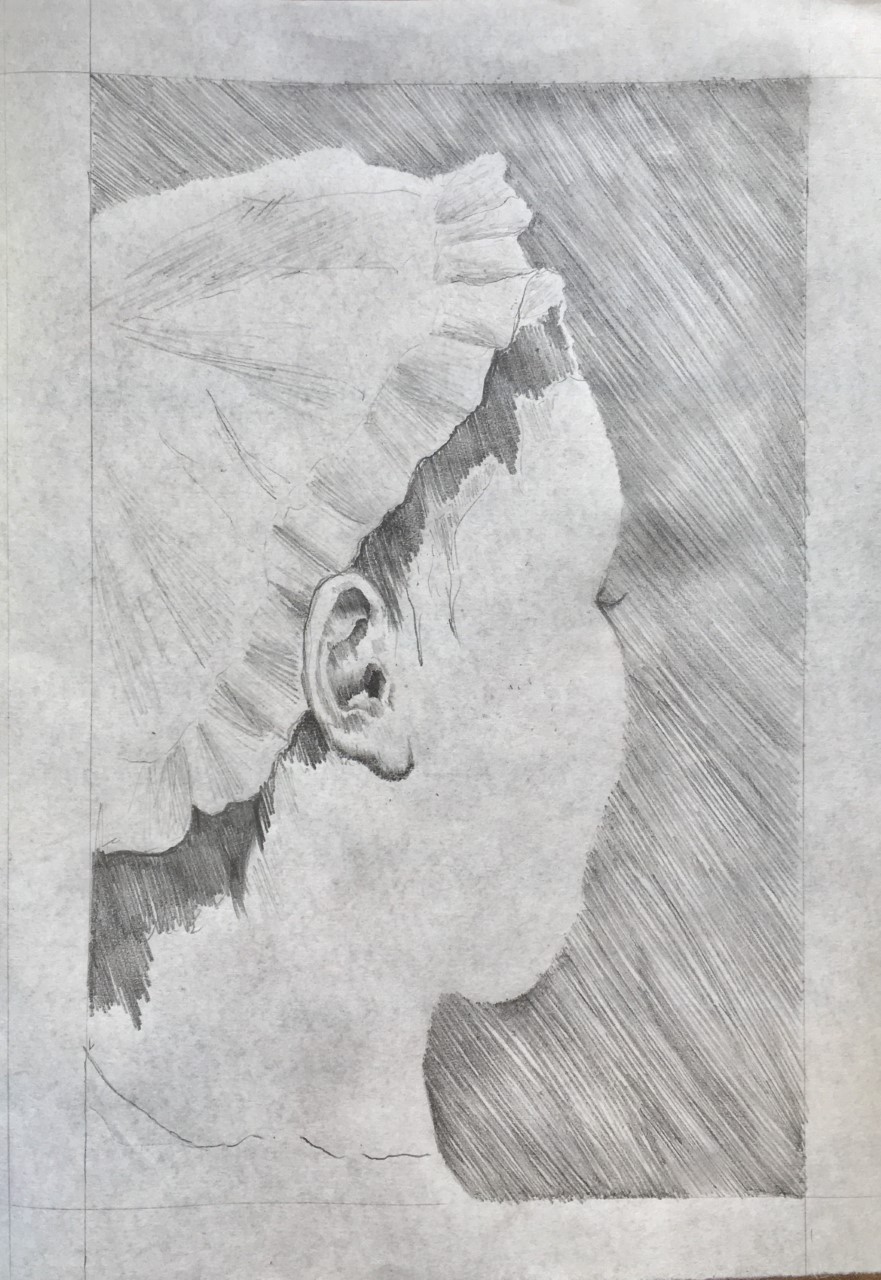

It is a very ongoing process. Usually, I become interested in a certain image and then that develops into lots of other things. My focus on the pastoral started from me looking at eighteenth century paintings of aristocratic women, who had been depicted as shepherdesses. The clothing they wore and the settings shown were impractical and fanciful. That led me to think more about the romanticising of the countryside, and how it is used as a landscape for political debate. Images like that are representative of a collective desire for an idealised past, a longing for something that didn’t actually happen, or never even existed. I then connected these ideas with contemporary politics, thinking about how this idea is deeply rooted and hidden within the rise of nationalism. Then all that thinking comes out in my work. Right now I’m making a shepherdess outfit!

Amazing! Have you ever tried to make clothes before?

I did a tiny bit on my foundation [Art Foundation Diploma course], but apart from that, no. In lockdown I have been doing a lot more sewing. For the shepherdess work, I’ve made an underdress, as well as a corset to go on top of it, a petticoat, and some hip pads so that the dress juts out. At the moment I’m also making a straw bergère hat from scratch. I’ve used wheat straw for this, so I had to deep dive on the internet until I found one of the two sellers of crafting straw in the UK. You have to soak it beforehand, then you plait it, and then you sew the plait together, manipulating it into the shape of the hat.

That is the best new skill I have heard anyone learn during lockdown. Some people are learning to bake banana bread or learning a new instrument, and you’re soaking your own wheat straw! I love it. Other than wheat, what else have you been doing to keep yourself entertained?

I’ve been listening to music and to podcasts. I’ve really enjoyed Moses Sumney’s new album. And Charli XCX’s lockdown album is amazing. It’s mad that she can still make stuff like that at the moment. Yves Tumor released a new album which is really good as well.

Do you think that lockdown has changed your art practice dramatically?

It has definitely changed my practice. At the start of lockdown there was so much pressure on people to be productive, when it was really such a stressful time. People don’t work for every hour of the day normally, so why should you expect yourself to do that in a time which is also full of anxiety?

Has it been weird being outside of a studio space?

When I was on my foundation [course], I did a lot of my work at home. I’m lucky that we have the space to, I can function and can work here. But, without the studio, you don’t have any of the dialogue that informs your work. It can be quite challenging. Like a lot of other people, I have been feeling quite useless. Without speaking to tutors and friends and other artists, I have found it hard to have faith in my work sometimes. Without the studio there is no community of artists or young people to challenge each other and talk about work.

Do you think that means that your practice will have changed in the long term? Or do you think things will return to normality once you can go back to a studio?

I guess my practice has changed, but I think that might just be the result of what I’m getting interested in now. It is a lot more craft based and hands on – a lot of my friends who don’t study art have used lockdown as a time to do more craft as well, which is really nice. I think I’m interested in looking into the consequences of unseen labour, not just in art but everywhere. I think especially now people are addressing that more, and it’s hopeful that people are being given recognition for their work, and others are using their platforms to address these issues.

I get what you mean, essential work is now finally getting the acknowledgement it deserves.

You can find Chantal on Instagram at @chantalgoulder.

Featured image: For Greta, March 2020, courtesy of Chantal Goulder.