On the anniversary of her death, MAYA WILSON AUTZEN reflects on how this year’s BLM movement has shed new light on Toni Morrison’s novels.

The fifth of August marked a year since the passing of the iconic novelist Toni Morrison, and the legacy she left behind echoes powerfully amidst the recent resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement. As the first African American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, her work retains great significance. The current climate surrounding the BLM resurgence has made many of us realise that too often black literature has been omitted and ignored. Morrison’s works have the capacity to disrupt the traditional canon as they educate and move readers. Whatever reason you may choose to pick up one of her texts, I personally could not recommend them enough for the enthralling marriage of brutality and beauty.

Born in 1931, Morrison experienced segregation in the U.S first-hand. Her parents, George and Ramah Wofford, fled to Ohio to avoid the extreme racism of the south. When she was only two years old, the owner of the building her family lived in set their home on fire whilst they were still inside because they had been unable to pay rent. Throughout her life she continued to fight for equality, exposing and challenging prejudiced institutes and habits: ‘In this country American means white. Everybody else has to hyphenate.’ Toni Morrison’s fiction was radical and revolutionary in that she brought black lives to the forefront of the narrative.

My favourite of her eleven works – and indeed one of my all-time favourite novels – is Beloved, which follows the story of mother and former slave Sethe. Sethe’s story is rooted in the real experiences of a black enslaved woman, Margeret Garner, infamous for killing her own daughter in 1856 to protect her from a life of slavery. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1988, Beloved explores the bonds of motherhood and family and how these are destructed and violated by the institution of slavery. Morrison’s fragmented structure flits between the past and present, reinforcing the inescapable nature of history and the recurring damage it produces.

In Beloved, Sethe makes the ultimate sacrifice as a mother to ensure her child will not be victim to the horrors, torture and rape that came with life as an enslaved woman. The reader follows as she attempts to live in the present while dealing with the traumas of her past. It is a brutal, honest, heart-breaking yet beautiful exploration of the poisonous effects of slavery on motherhood. Beloved’s poignant, poetic language never fails to move. Morrison’s mixture of the gothic, supernatural, and magical elements with the hard, cruel everyday elevates her fiction, eternalising black lives and voices that otherwise remain left unheard. Each character seems to hold the weight of generations of pain and history in their narratives.

Morrison continued to explore the bonds of motherhood and community in one of her later novels, God Help the Child. In this, motherhood is restricted to pure survival, providing the tough love necessary to prepare children for life with darker skin: ‘If I hadn’t trained Lula Ann properly, she wouldn’t have known to always cross the street and avoid white boys.’ Morrison’s writing explores the darkest sides of maternity, and the complexity of protecting a child from perverse, systemic racism.

Morrison’s focus on the past forcefully intertwined with the present is a crucial lesson. Today we must all examine our pasts in an attempt to repair and compensate for damage caused by the repercussions of colonialism, slavery and racism. The recent removal of the statue of Bristolian slave trader Edward Colston during the BLM protests forces the UK to re-examine its past and acknowledge the part it played in the inherent discrimination towards black communities.

Studying English Literature as Morrison did, she teaches and reminds me of the power of words and writing. Perhaps more than ever, we need spaces for black voices and black literature. It is time to change the canon that has for too long been occupied by straight/cis white men. If you do one thing this week, I urge you to go to your local library or bookshop and buy any one of Morrison’s novels. You will be inspired, educated and maybe even moved to tears by the gravity and emotion of her characters. We need to take autonomy of our education and awareness surrounding the BLM movement, and literature is a great place to start.

I leave you with my favourite quote from Beloved, which I think symbolises the empowering and inspiring legacy Morrison left behind: ‘You are your best thing.’

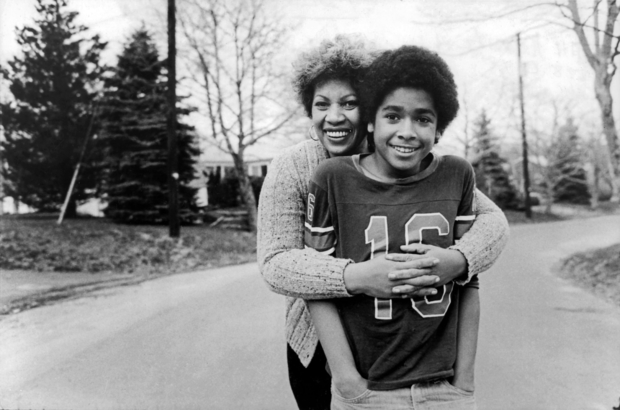

Featured image courtesy of Jill Krementz, All Rights Reserved