WILL FERREIRA-DYKE sits down with DANIEL LUCEY to discuss the numerous facets of his practice, the experience of getting into and out of creative ruts, and the artist’s plans for when he returns to London for his fourth year the Slade.

Daniel Lucey’s work is concerned primarily with the way the body interacts with the world, particularly through the senses. Inspired by Alan Kaprow’s Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (1993), Daniel seeks to find a ‘true’ way of recording experience, describing his work as a ‘composite of experiences’ that blend sensations such as sight and hearing with emotions such as desire, and phenomena such as memory. For him, painting can ‘be about a day in the snow, the smell of a rose and the end of a relationship’ so long as there is a palpable textural thread bringing all the ideas together. Fundamentally, Daniel does not want his work to sit outside of the world.

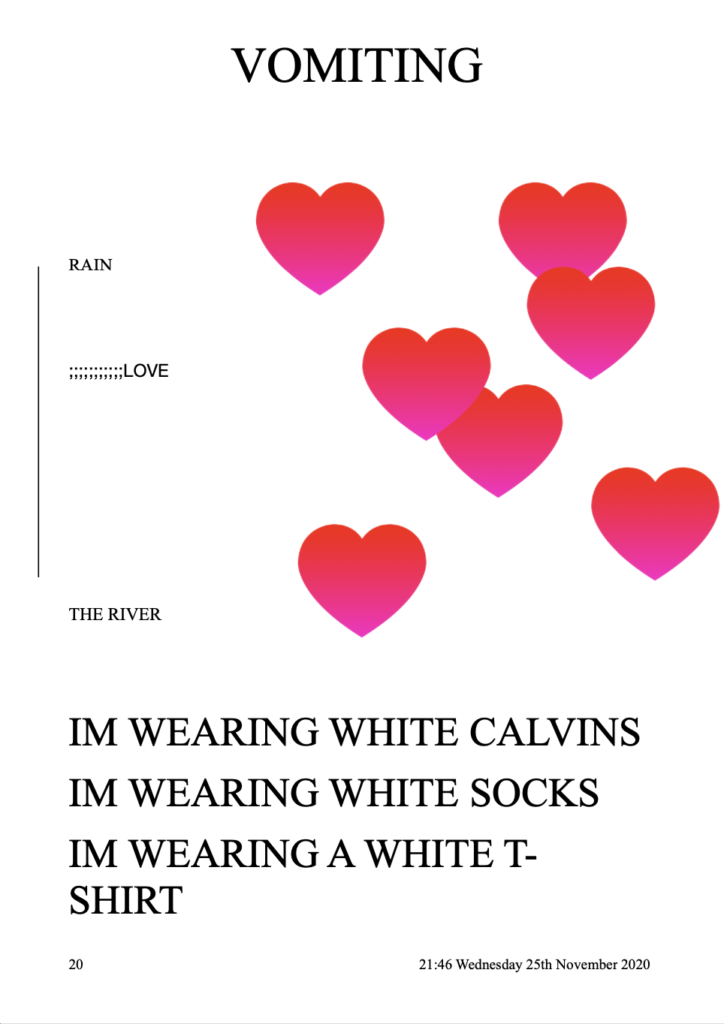

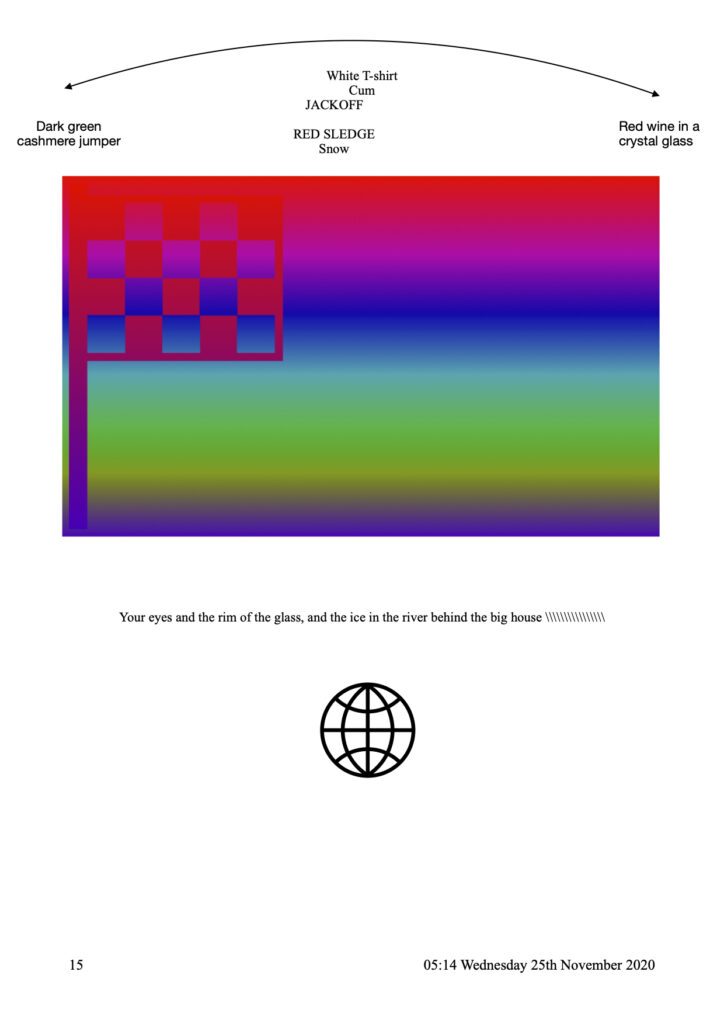

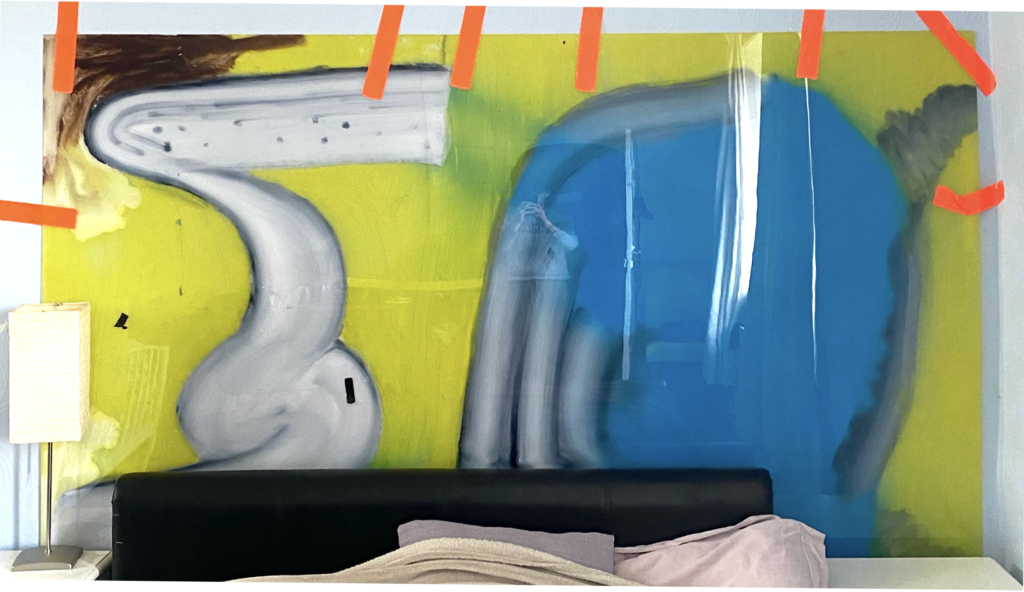

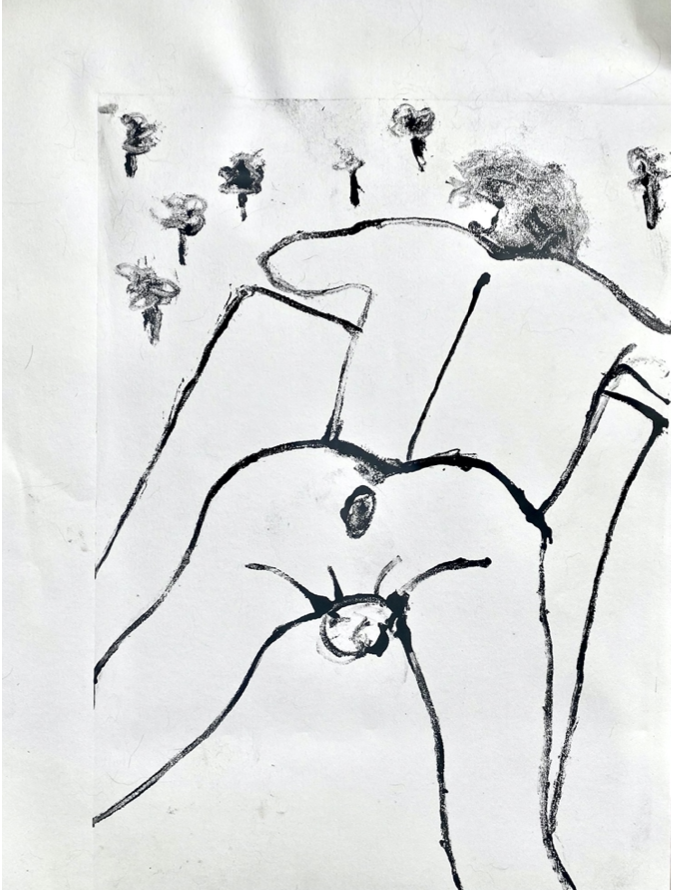

During his two years back at home over lockdown, Daniel’s work has manifested itself in three decisive stages. His digital ‘Instances’ are text based works that act almost as diary entries, quasi-poems where the artist can freely concretise his thoughts. Daniel also creates ‘backwards paintings’, where he paints on the back of perspex, and then once finished, turns the surface around to reveal an unknown image. His recent ‘Boy Print’ series reflect his interests in queer theory, and in the theatrics of reveal.

So you have been off campus for a while – did you take a year out?

We went into lockdown in March of my second year. We had only had five or six months of teaching, and then I came straight back home and have been in Durham ever since. Of course there have been ups and downs, but weirdly it’s been a good little break. I can’t wait to get back to London – I’m going into my fourth year, so annoyingly I’ve only got one year left.

How has your work changed during this year being at home?

It was strange. As soon as I came back, I set up a studio in the kitchen. I found I couldn’t do anything during the day, so I worked at night. I continued the paintings I was doing in second year and in the middle of the night thought they were dead good, and then would wake up the next morning and realise ‘Actually, these are shit’. I wasn’t really happy with anything I was making. I realised through tutorials that this was because the works weren’t informed by anything. I don’t like the idea that my work is self referential. I don’t want to make paintings about painting. I’ve always wanted them to be informed by the rest of the world. The mundanity and monotonous reality of the pandemic meant that everyday was kind of the same. It felt like all of the work started to become about making the work.

How did you counter your pandemic-induced art rutt?

See, I was quite stubborn. Everyone was like, ‘Oh, you need to do some reading’. However, I thought that I had suddenly forgotten how to paint. I didn’t want to take weeks off, because I thought that when I came back it would be more difficult. So I ended up doing around thirty canvases – I call them canvases, not paintings, because they were unfinished – which have since formed a collective and shared a residency in the bin. Eventually, I did take a week off and I read. The reading I was doing, mostly theory, was trying to get the rest of the world back into my practice. I was reading that and a lot of queer theory as well.

Reading is always good and queer theory is alway fun! Who were you reading?

Well, in first year one of my tutors said I needed to read queer theory, however, again, I was stubborn. Everyone kept being like ‘every painting you paint has a massive penis in it’. I don’t think I was doing it consciously, it was a little bit Freudian. Only after reading all this theory did things start to click into place. I read Leo Barasris’ Is the Rectum a Grave (2009) and that was really interesting. It was a bit dense, and I had to read it a few times. The other person I read around that time was Lacan – even heavier! The section of Lacan I found most interesting was ‘objet petit a’ . Mearleu Ponty writes about this too, I think he calls it ‘the flesh’. Both are referring to an image that doesn’t have any form. It was something that you knew was there and that you could recognise and feel, but you couldn’t necessarily point to. Take, for instance, catching someone’s eye; you can’t point to that gaze as you would end up looking at their eye. I realised this was what I had been trying to do in my work this entire time. I was trying to get at the ungraspable. This is why I was having a hard time with it, because it would take a while to accept what I had done was the truth.

After your reading, how did you get back into your artistic practice?

I started making what I call ‘instances’, my texty/imagey works. They were kind of stupid, but they ended up being really helpful. I quickly realised these ‘instances’ were basically sketches for my paintings. Before starting a painting, I typically made lists of connected words and they would form the subject of whatever was going to be in the painting. They weren’t always visual – sometimes they related to smells, sensations and so on. This helped me figure out a way of going into a painting knowing what it would be about. Initially I was making them for the canvases, but I also enjoy them as a body of work in and of themselves. The ‘instances’ also revealed that the work is always personal and I can’t really escape nor deny it. Denying it would be untruthful. I think with abstract painting there is historical, heroic, bagage and I wanted to get away from that.

How do these ‘instances’ take shape? How many works are there in total?

Each ‘instance’ is titled with a number on the left hand side. They are all formatted in the same way, so there is a sense of order and structure. I don’t really want to call them poems, as if I called them this there would be an expectation of what they should read. Though in reality they are kind of like concrete poems with images. Titling them ‘instances’, I could use whatever I wanted as material, things which were not necessarily graspable. I could incorporate all the different senses. Because there was so much possibility in what these could be, I felt there needed to be an orderly formatted structure, so that I could wake up, do one, finish it and then start the next. There are 200 ‘instances’ in total. I am happy with, say, forty of them. And then 160 others that are going in the bin! My plan is to first make a zine just to get them out there. I can’t really see them ending anytime soon, they feel like the perfect way to tie ideas together, a blank space ideas can be put onto. They can be done very fast and I don’t feel any pressure for them to be perfect. They are in essence free from constraint. They are always very beneficial to look back on, because of the way they are formatted. I find things come up in these ‘instances’ which I wouldn’t have noticed otherwise.

I see references to Rothko and Hodgkin in your work; in terms of artists who do you think your art is informed by?

See, I quite like Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs – they are simply beautiful and balanced. They do that thing that I’m trying to do: capture the flesh, that ungraspable thing. I keep going back to him. In terms of painters, I love Howard Hodgkin. He’s a weird one for me, as in second year he was always the reference I’d be given. I can very much see the similarities in his work to mine

So these ‘instances’ helped inform your ‘backward paintings’, can you talk to me about these further?

I make the ‘backwards paintings’ by painting onto the backside of perspex on the floor, and then I build the painting’s background. The foreground is painted first, and then the midground and then finally the background. I realised that this seems to be the way I’ve always tried to make paintings, hence why when I’ve painted them on canvas they haven’t really worked. I read Phyllida Barlow’s essay ‘The Hatred of the Object’ (2003), and I really liked the idea that I could have a painting process that was involved, or ‘hot’, one where I could utilise the physicality of painting. I like the idea that this process is done by hand but the end result looks like it could have been manufactured. I wanted to produce something that was active. My paintings on canvas seemed kind of dead. I would paint them, they would go on the wall and they would die. But because the surface of perspex is reflective, as stupid and as gimmicky as it seems, when the light changes in a room the painting changes, there feels like there is an interaction with the space, that the work is alive within its environment. Also the way that they’re painted, I don’t know what they’re going to look like until they are on the wall. This process allows me to see the painting for the first time at the same time as any other viewer would see it. It feels like a surprise or a reveal. I don’t know if it’s theatrical but I like revealing it to myself, because it feels as if it came out of nowhere.

I saw on your Instagram recently you have been creating a series of ‘Boy Prints’, what was the appeal to go over to printmaking?

Printmaking is weirdly a similar process to the ‘backwards paintings’; there is a similar reveal here also, an element of distance between me and the thing. I like the idea that my hand isn’t directly touching the surface of the perspex. I think that’s because when I have a page, canvas or surface in front of me I can see my hand making gestures, then I try to correct myself. I can see myself trying to modify and alter the forms I am creating. This comes back to the idea that I want the work to feel truthful. If I have way too much control over exactly where something goes then I feel restricted, I paint what I think it should be rather than what it is. That’s when I end up making decisions I wouldn’t ordinarily make, decisions made for other people. The only reason I ended up doing a series of ‘Boy Prints’ is because that was the subject that ended up coming up the most in my ‘instances’. I wanted to see if I could produce something mostly figurative that still made sense with the paintings.

What do you hope to achieve in your final year?

I think at the minute for final year, I want to do a series of backwards paintings and complete a book. That’s what I think I will show. Each ‘backwards painting’ holds a non-linear narrative to it, in the same way that each ‘instance’ has the potential to later become a painting. I like the idea of putting three of them together. That is what I think I will show.

Final question: what would be your dream project? Talk to me about scale, space, materials, everything.

It is kind of wild so bare with. You know when people propose, and they fly a plane in the sky and write ‘will you marry me’ with the smoke? A while ago I had the idea that I wanted an ‘instance’ to occupy that sort of space. I like the ephemerality of this idea, as well as it being a bit cheesy and camp. It would also be very public – which would be strange to show this almost diary-esque type work. I would also like to create a large-scale series of ‘backwards paintings’. It would be interesting to see how they all converse in a room together because I’ve never really seen them like that. I have only ever seen them in the context of my bedroom. From bedroom to white cube please – à la Tracy Emin! Another dream project would be working with scent or fragrance, which is something that always comes up in my work – though I’ve found it difficult to convince people what a particular area of paint is supposed to smell like. I wouldn’t want to start adding actual scents. The ‘backwards paintings’ are enough to have this gimmicky nature. Truthfully, making anything outside this house would be a total dream; the journey back to Slade is soon approaching.

To follow Daniel’s final year, find him on instagram @daniel_lucey

Featured images: Left: Daniel Lucey, HEAVEN, 2019-2020, Right: Daniel Lucey, 5 Star Showdown (gym socks), 2020. Images courtesy of Daniel Lucey.