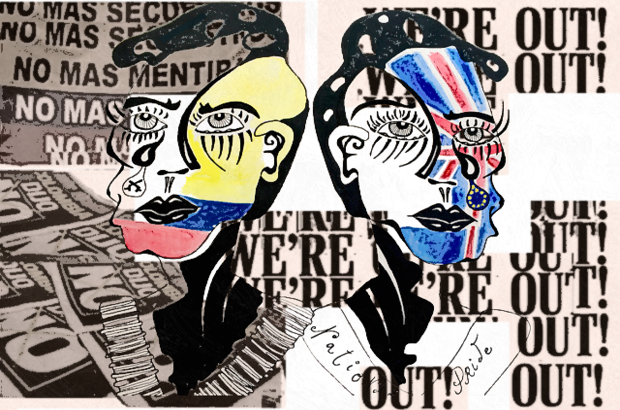

OLLIE KENDRICK compares the motivation of the Right in the UK and Colombia in their recent referendums.

The final resting place of Pablo Escobar is nestled away in the corner of one of Medellin’s more exclusive cemeteries, overlooking the rolling hills of the Colombian Department of Antioquia. His is a modest headstone, with a few wilting bouquets adorning both his mother’s and father’s graves beside him. It is perhaps an appropriate resting place for such a divisive figure, reflecting neither his status as the most successful drug lord in living memory, nor his extensive work as the philanthropic ‘El Padrino’. It is a place afforded a certain serenity, a place where the violence of his legacy is forgotten in favour of the prosperous peacetime in which Colombia now thrives as the third largest economy in Latin America. Escobar, however, continues to divide the region. Many are unwilling to forgive the atrocities committed by his cartel, whilst others hold him in much higher esteem as a Robin Hood figure set against the backdrop of state failure. For some his most heinous crimes can be excused and for others they are simply unforgivable.

Nowadays, although not quite to the same extent, one can see a similar sentiment in popular perceptions of the FARC (The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia- People’s Army). The FARC began life in 1948 when the leader of the Liberal Party, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán Ayala, was assassinated, resulting in the creation of the FARC-EP in 1964 as the military wing of the Colombian Communist Party. Since then, they have unflinchingly opposed the purported greed and elitism of the Colombian administration and have come to embody, for some, benevolent left wing and progressive ideals. However, excluding brief periods of ceasefire, they have led a sustained, violent guerrilla campaign against the Colombian military–a conflict which has inflicted terrible loss on Colombia, over 220,000 deaths throughout the 52-year long war–and have conducted numerous kidnappings. Over the last few years momentum has been building towards a peace deal, culminating in the signing of the Havana Peace Accord this summer. However, earlier this month, the Colombian public voted against this potentially revolutionary deal in a referendum.

It seems that despite peace being within touching distance, the right wing and its media were able to exploit popular bitterness for their own political ends. This has an unnerving resonance for those of us who have faced a summer of Brexit bigotry. The Leave Campaign was founded on false conceptions concerning immigration and sovereignty, and led by politicians veneered with a certain type of British ‘charisma’ concealing very personal political ambitions. In the cold light of Post-Brexit, these formerly veiled ambitions are not too difficult to determine.

The political opportunism of Gove and Johnson is disturbingly mirrored in Colombia by a similarly repugnant pair: ex-president Alvaro Uribe and ex-General Inspector Alejandro Ordóñez. Both men are famed for their right wing stances and emphasis on security, and have actively campaigned against a peace deal with the FARC. Many people have equated the positions of Uribe and Ordonez with a vote for justice, albeit a justice with very few concessions to the FARC. Supposedly, the pain that the FARC has caused Colombia cannot be forgiven through a process of transitional justice in which legal impunity and formal political representation for Farcare exchanged for peace.

Although this undoubtedly motivated many ‘No’ voters, it was not one of the key mobilisers. Much like the deplorable rhetoric of the ‘Leave’ campaign against refugees, the ‘No’ campaign in Colomobia found its own particular set of people to villainize. Here, it was those supporting increased gender equality and a more inclusive sex education curriculum in schools. Colombia’s education minister Gina Parody, a close ally of current president Juan Manuel Santos and one of the country’s first ever openly gay ministers, recently created a sex education manual for schools that included information on homosexuality. This ultimately led to a virulent attack on Santos and Parody: numerous marches were staged against her, and they were accused of undermining ‘family values’ and of ‘homosexual colonisation’. This rhetoric was skilfully employed by the ‘No’ campaign to harness the resentment towards these policies, and they even went so far as to create a fake government sex education manual depicting a gay couple having sex. Much with immigration with regard to the Brexit vote, the right wing resistance to liberalisation became unashamedly and inextricably linked to the peace deal. A campaign founded on opposition to overly lenient transitional peace was soon hijacked by an opportunist and evangelical right-wing coalition. Sadly, this combination was to achieve a majority of 60,000 in the recent referendum.

Brexit showed us the lengths to which the right wing of our country would go to achieve a political end even they themselves had little grasp of. They manipulated a base level of intolerance, promising a greater level of control. But as it transpires, they are now in control of a destiny no one particularly relishes. Uribe is in a similar position, albeit with far higher stakes. It’s widely known that the FARC were by no means united in their willingness to lay down arms before the referendum, and it is clear that the provocation of the ‘no’ vote and further negotiation may tip many already sceptical FARC members over the edge. This is an unthinkable situation, and would most likely lead to further violence. It has been speculated, however, that this is precisely what Uribe wants – an excuse to return to his policy of total war against the FARC, and his triumphant return to the Casa de Nariño in the 2018 election as a result. While it is difficult to foresee such events, it is certainly not impossible. Just as with Post-Brexit Britain, it is vital that Santos renegotiates carefully in order to establish a peace deal that not only fosters peace, but also ensures a bloodless transition.

Given the harsh realities of war, we must be careful not to equate the idea of forgiveness with that of a peaceful justice. The Colombian people may never be able to forgive the FARC, but it has become clear that they can, and want to, forgive war and live in peace. It is this difficult but ultimately redeeming compromise that the right wing have sabotaged – much like the Brexiteers, who capitalised on working class frustrations. While we can hope Colombia should still be able to achieve peace, and the UK may well withstand the storm of Brexit, it is the Right who are really losing. Their desperation for preservation holds our idea of humanity hostage, but in reality they will prove unable to corrupt the transcendent progress that Santos and others continue to fight for.