INDIA CHARTER sees hope for a creative rebirth in Sadiq Kahn’s post-Brexit London.

‘When you voted to leave the EU but you gunna die soon so it’s not your problem’: Brexit provoked the customary British humour that masks our most cataclysmic political decisions, making our Facebook, Twitter and Instagram feeds blow up with jokes about 79-year-old Gary from down the road dictating our tainted, hopeless, non-EU futures. The sombre post-Brexit ambience leaves little in the way of optimism for British millennials. Within this disbelief and uncertainty, a resounding unity has emerged: young people are unhappy with the nation’s decision. Yet while we woefully discuss the fall of the Pound, roving funding cuts, closing borders, and a stomach-churning spike in hate crimes, it is perhaps possible to identify a sliver of hope, which could be the seedling to reinvigorate creative London.

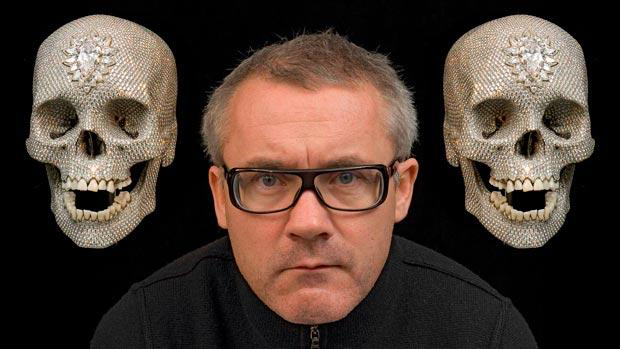

Since the roaring success of the 1990s’ Young British Artists, London’s art market has become saturated with multi-million-pound big-dogs. Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and their contemporaries exploited a London in economic decay, manipulating cheap and expansive ex-factory spaces into studios and forging a celebrity brand that enticed investment from Charles Saatchi and global millionaires. We all know the gentrification stories that followed – East London became cool, investment followed and low income residents, including artists, were forced out by escalating property prices. Where, then, does this leave today’s young artistic Londoners? Unable to engage in the market or to access adequate studio space in the property-obsessed city. London undoubtedly continues to be crawling with under-the-radar talent, yet the art market is devastatingly overshadowed by the city’s interest in profit margins and calculated art investment by city firms.

Conversations with young London artists over the past year have demonstrated encouraging resilience to the tough (and now even tougher) times. With the help of various non-governmental initiatives, creative consultancies and organisations, young artists are determined to push for public exposure and willing to diversify their talents and create new communities in order to survive. Nevertheless, popular migration trends show that young artists are moving out of the capital.

It would be too easy to blame the City Fat Cats alone for this tightening of opportunities: responsibility must also sit with policy makers. Our last two governments’ neglect of once-valuable cultural policies has provoked thousands to take advantage of EU passports and set up practice abroad, in our cooler, cheaper European Counterparts like Lisbon, Warsaw and Berlin. In her 2016 book ‘Be Creative: Making a Living in the New Culture Industries’, Angela McRobbie condemns the diminished interest the government takes in the arts: without rent controls in our creative enclaves, artists will continue to be priced out of their practices. A threat of creative deficit is all too real and without young and local talent creating sites of resistance, we will only see our streets whitewashed, our music venues closed, the bubbly creative chutzpah of Soho or Dalston lost, at a faster rate.

Sadiq Khan’s recent election as London Mayor election offers a beacon of hope, promising updated cultural policies and funding initiatives. Unlike his predecessor Boris Johnson, Khan acknowledges both intrinsic and financial value in London’s creativity, vouching to support the city’s various creative sectors through schemes such as ‘Creative Enterprise Zones’ and an annually elected ‘London Borough of Culture’. Updating Thatcherite ‘Business Enterprise Zones’, which saw the financialisation of London, Kahn’s policy specifically targets the problem of adequate and affordable studio space. This kind of politics, which frames creative industries as equally as important as finance, is a huge victory for millennials engaged with London’s arts and cultural scenes.

We might be disheartened or furious with the nation’s referendum decision, but as Theresa May unveils her (lack of) Brexit plans, the reality of it happening is becoming inescapable. It is now crucial for those who wanted ‘In’ to search for the potential in our new horizons. Brexit means that cultural migration from London to Berlin (and back again) will become more difficult. Already transporting even physical art itself across European borders is becoming more difficult. We therefore need London to fill the void of easy access to other EU capitals. Equally, various newspapers have forecast housing price falls in post-Brexit Britain, which – if harnessed by clever politics – could create an opening to ease out-of-control rent prices in the cosmopolitan capital city.

London’s diverse and rich histories shaped what was once considered as the greatest cultural and artistic hub in the world. Despite our pessimism, Brexit has left us with an opportunity to focus our attentions on our crumbling domestic art scene. Thatcherite policies of the last thirty-five years have worked well to advance Financial London – but what about the industries left behind?

Perhaps it is not enough to say that Brexit-induced house price falls and reduced ability to migrate elsewhere in the EU will save our emerging art scene. It is, however, a promising opening for an intense re-cultivation of London artists. So much great art has been borne out of a time of crisis, be it personal or national. If nothing else, post-Brexit Britain, with its 14% lasting increase of hate crime reports and a truly disaffected youth, is looking like a nation on the verge of crisis. Not least, Brexit stands as a signal to call for change – for us to campaign in support of reduced rent and more funding, to help ensure that the Creative Enterprise Zones flourish, and to contribute to our artistic communities in order to inspire young talent to settle in the city. Brexit has already been the catalyst for protests and demonstrations across London; a mass artistic movement could be next.

Let’s make post-Brexit Britain a time for us to encourage young creatives to settle and stay in the city, to exploit a dip in housing prices and reignite the creative flame that once crowned us ‘Cool Britannia’.

Part of a conflicting opinions series. To view the case AGAINST, click here.