POLLY RODIN examines whether the recent action of Sisters Uncut merits comparison to the radical and militant Woman’s Suffrage Movement.

I can understand empowered modern women thinking that the concerns of the suffragettes are now issues belonging to the past. However, the rallying cry of Sisters Uncut, ‘Dead Women Can’t Vote’, serves as an urgent reminder that the struggle for women’s liberation is not historical. Their slogan refers to a very devastating fact: two women die from domestic violence every week, and nearly half of the British women killed by men die at the hands of their partners. The sisters staged a ‘die-in’ at the premier of Abi Morgan’s film Suffragette to protest against government cuts to domestic violence services, which act as an indispensable cushion for the most vulnerable women. The controversial and illegal nature of this protest naturally leads to comparisons with the militant tactics of the twentieth-century suffragette movement, but was the physical protest of Sisters Uncut far-reaching enough to deserve the title of the new suffragettes?

Almost exactly 100 years ago Emmeline Pankhurst dared her contemporaries to fight for suffrage using the persuasive slogan ‘deeds not words’; today there is a proliferation of feminist rhetoric online, but it is still newsworthy when a protest follows Pankhurst’s incitement to action. Both groups of women understood the effectiveness of physical tactics in a political campaign – the Suffragettes’ act of chaining themselves to government buildings and the Sisters’ ‘die-in’ both resolutely and physically articulate a refusal to move until listened to and noticed. This tactic evidently works: Sisters Uncut has successfully placed issues of domestic violence in the minds of the British public, stimulating articles in major newspapers and passing the litmus test of modern protest by creating a twitter storm.

The media response to the Suffragettes was far less sympathetic. Ridiculed as single women who just haven’t found husbands yet, or dismissed as ‘hysterical’, contemporary press aimed to undermine their serious demands and silence their angry voices. Responses to Sisters Uncut in current media have been far more supportive, often allowing the Sisters to speak for themselves, which they did, testifying to the advances made in the last decade in the attitude to women’s rights. However, there have been clear attempts to silence the Sisters: I was struck by the way those hosting the première physically and forcefully dragged the demonstrators away – reminiscent of the photographs of struggling Suffragettes being contained and even beaten by the police. While the reaction to the Sisters does not in any way compare to the horrific brutality faced by women’s suffrage campaigners they were certainly not treated with respect. It is ironic how, during the première of a film intending to give women a voice, ‘Sisters Uncut’ were not allowed to fully exercise theirs.

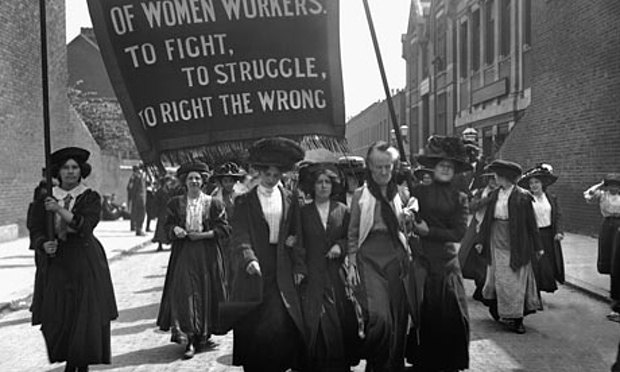

Sisters Uncut insightfully identified this particular film première as the perfect context for their demonstration. Although the role of women of colour has been obscured, Suffragette does highlight a different angle of the story we are used to, atypically following the actions of a group of working class factory women who were “foot-soldiers” in the fight for the female vote. This strengthens comparisons between the suffrage movement and a campaign such as that of ‘Sisters Uncut’: intersectional, grass-roots, and spurred by the personal experiences of its members, many of whom were motivated to act after experiencing domestic abuse first-hand. The Sisters’ action gained the support of cast members Helena Bonham Carter (incidentally a relation of Herbert Asquith, Prime Minister at key stages during the women’s suffrage struggle) and Carey Mulligan; Bonham Carter calls their action the ‘perfect response’ to the film.

While I applaud Bonham-Carter’s endorsement of the protest, I can’t help thinking that her use of the word ‘perfect’ – like the line on the Suffragette promo posters ‘the time is now’ – doesn’t ring as true as Shanice Octavia’s knowingly similar statement, ‘we want to create the feeling that the time is now and we thought the première was the perfect opportunity to voice that message.’ Octavia suggests that the Sisters’ action isn’t a response to the film, it’s a strategic attack, which makes use of the ‘press attention and the feminist nostalgia’ in attendance at such an event. I think she’s right to use the word ‘nostalgia’ – there are elements of the film Suffragette that, in comparison to the decisive action of Sisters Uncut, appear self-congratulatory and passively sentimental, and dangerously spread the complacent idea that we are ‘in a post-feminist era’. The protest sliced through any of the film’s latent good intentions by actually doing.

One distinction is crucial: between lying down on a red carpet full of A-listers and risking your life placing your body into the path of a charging horse. Laudably, Sisters Uncut are the first to realise their actions pale in comparison to the radical nature of their militant predecessors. The suffragettes spilt corrosive acid into letter boxes, cut telephone wires, defaced artworks in major national galleries, set fire to the Prime Minister’s house. However rather than being judged negatively as ‘not-radical-enough’ it is important to see the Sisters within their own context: they are a rare example of courageous, physical activism in the UK today and they effectively bring to our attention the complacency of conceptual modern feminism – by reminding us of the very physical fact that so many women today still lead lives debilitated by domestic violence.