POLLY CREED shows that Kesha is, tragically, only the latest victim of the music industry’s attitude towards sex.

Crumpled at the back of a court room, Kesha sat and wept, her face blotched and contorted with pain and tears. A New York judge was ruling against her request to be released from Sony Music and working with Dr Luke, the producer who Kesha claims has abused her for years – plying her with drugs, repeatedly assaulting and raping her. Immediately countless ‘big names’ clamoured to her aid: Lena Denham wrote a long, impassioned article condemning the outcome of the case; Taylor Swift gave Kesha $250,000 to help with ‘her financial needs’; #FreeKesha trended on Twitter; and Lorde, Ariana Grande and Lady Gaga were among those who also rallied to support her. However, despite the public outcry and media coverage, the verdict still stood that Kesha must remain shackled in her contract with Sony, signed when she was only 18, and forced to work with her alleged abuser.

Sony has at last bowed to public pressure and this week dropped Dr Luke, although the delay demands whether this decision is a sign they are finally taking the artist’s safety seriously, or because it is now more expensive and troublesome for them to protect Dr Luke than his alleged victim. It remains to be seen whether Sony’s decision is based on a will to, finally, continue to the right thing, or whether they bowed under the pressure of this one high-profile incident. This deeply troubling incident unfortunately illustrates the kind of treatment women in the music industry all too regularly receive at the hands of their record labels – and indeed the law.

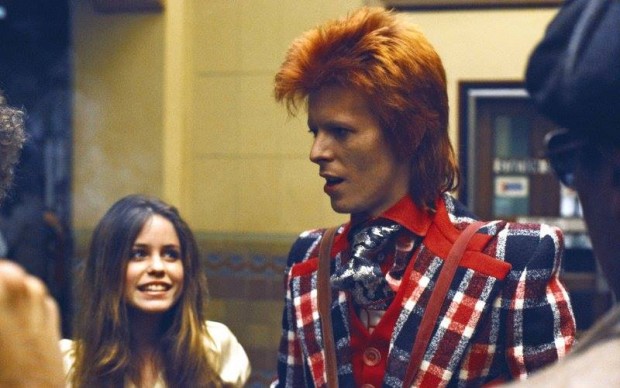

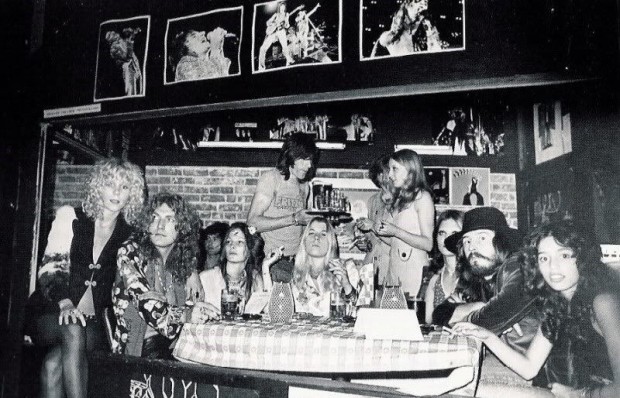

Kesha’s is not an isolated case, but part of a much wider trend of sexual harassment that has been going unpunished and unacknowledged in the music industry for generations. When David Bowie died last month there was an outpouring of grief, but very few stopped to mention the fact that during the early 1970s Bowie was part of a group of musicians (including Iggy Pop, Jimmy Page, and Mick Jagger), who hung out in LA nightclubs such as E Club, English Disco and the Rainbow, preying on teenage girls. These girls, who included Lori Maddox and Sable Starr, were generally aged between 13 and 15 and became known as the ‘Baby Groupies’. As they popped pills and entered the hotel suites of rock stars along the Sunset Strip they may have delighted in the attention thrust upon them by their pop star idols and their glamorous initiation into the world of adult life. The fact remains, however, that these were not adults but children: children, who were unable to give their consent – making David Bowie, along with Page, Jagger and Iggy Pop, rapists. Rather than jump to the aid of the girls who were systematically groomed and exploited by these pop stars, the media and society has romanticised the ‘Baby Groupies’ of the Sunset Strip, celebrating their role in pop history. They were even immortalised in the 2001 film Almost Famous, featuring Kate Hudson, Zooey Deschanel and Jimmy Fallon.

More recently, rapper Tyga came under fire for allegedly sending flirtatious texts to a fourteen-year old model. Tabloids were quick to demonise Tyga for his infidelity to Kylie Jenner in this saga, as well as sexualising the girl in question by splashing her photos across the pages of their papers. However most failed to acknowledge the girl’s youth, let alone recognise the fact that Kylie herself was only 17, and therefore legally underage, when she started dating the rapper. Here again was a blatant example of sexual harassment being trivialised and even fetishized in the music industry. While society and the media are willing to hold public figures such as politicians and presenters to account for the pain and misery they cause through sexual abuse (and rightly so), the standards applied to those in the music industry seem to be altogether different. Perhaps this attitude stems from that age-old notion that artists are somehow supposed to transgress moral and social boundaries. Instead of questioning and punishing artists for their sexual and moral misconduct, it is brushed aside as an expected aspect of the bohemian lifestyle – or even glorified. Their victims are treated not as victims, but as fortunate martyrs to their glamorous, creative cause.

It’s clear that the music industry has had a deep-rooted and incredibly troubling problem with sexual harassment for generations. From Madonna, who was raped at 19 as she tried to attend a dance class in New York, to Kara DioGuardi, the former American Idol judge who recently revealed in her memoir that she was date-raped by a well-known music producer. Despite DioGuardi’s relative power and security within the industry, she even felt unable to reveal her assailant’s name. The more I probe, the more I realise this industry is rife with stories of women being sexually harassed and abused, and feeling subsequently unable to talk about it openly. In January an anonymous woman, who describes herself as ‘a young woman working in the indie music industry’, set up The Industry Ain’t Safe, a Tumblr blog acting as a platform for women to share their stories of abuse and sexual harassment in the music business anonymously to publically name their abusers. Within days, the site was inundated with stories from across the world. The sheer volume of accounts, as well as the need for anonymity on the site, testifies not only to the scale, but also to the danger for women, who come forward, as victims of abuse in the music industry. It is shocking that in a society, supposedly striving towards greater gender equality and protection for victims of sexual abuse, women involved in the music industry still fear persecution and professional repercussions for naming their attackers.

In the music industry, power and contacts are everything and young artists are often at the mercy of rich, powerful producers and mentors. This, combined with the way society still expects musicians to push societal boundaries and transgress sexually seems to be at the heart of the problem. It is therefore down to the media and society as a whole to stop overlooking these cases of abuse and dismissing them as an inevitable part of the industry and instead protect these victims and call out their attackers. We must hope that Kesha’s court case – and the outrage it has attracted – constitutes a watershed moment for the industry as whole. No other women must suffer in the same way that Kesha has at the hands of wealthy, powerful producers and artists – and no other young girls must be sexually exploited and groomed by the idols. Tik Tok: it’s time to dethrone these ‘kings’ of the industry and hold them to the same standards as everyone else.