CAITLIN ALLEN explores the exploitation of gender stereotypes in food marketing.

As someone who suffers from debilitating bouts of food envy, I like to be certain that I’m making the right choices when it comes to the food and drink I purchase. For months, I struggled with the ‘Diet Coke versus Coke Zero’ dilemma, until one day, I heard an unsettling rumour: they’re exactly the same. A true millennial, I turned to the internet for answers. In my search, I found ‘roommatetrouble3’, a forum user who had bought a crate of Coke Zero, only to return home and find that his roommate had thrown them all away, due to the message emblazoned on the side of the box: ‘share these with a wingman/bro’. His roommate refused to apologise or reimburse him for his ‘sexist’ purchase. While this scenario may appear trivial, it raises an interesting point. Coke Zero’s marketing campaign is deeply entrenched in gender stereotypes.

It turns out Coke Zero and Diet Coke are virtually identical (only a slight difference in one of several sweeteners). Coke Zero’s creation, therefore, was a marketing flourish. Plenty of men like the idea of a less calorific Coke, but the ‘diet’ label is a deterrent. The word ‘diet’ is so heavily associated with the feminine, that to drink it would be emasculating. Thus, Coke Zero was born: a black can wielded by the ‘masculine’ footballers paid to promote it, effectively a ‘male’ antidote to the ‘female’ Diet Coke. This is a clear example of the way in which the marketing of food is so inherently gender-based.

Gendered food marketing happens everywhere. Time and time again, the same trusty assumptions are made: dainty, low-calorie foods for girls and hunks of meat for boys. In 2014, Carl’s Jr.’s absurd advert for their new ‘Western Xtra Bacon Thickburger’ featured a female body morphing into a muscular man before attempting to tackle their latest meaty offering. The caption reads, ‘Man up for two times the bacon’. While on the one hand this is tongue-in-cheek, on the other it epitomises the sexist marketing of food. It candidly delivers the message that only a man could possibly have the ‘strength’ required to handle such a meaty meal.

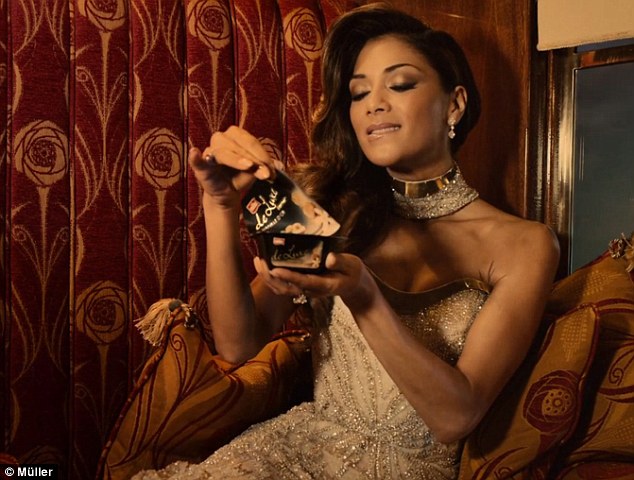

Meanwhile, women are busy reclining on sofas, sampling low-calorie yoghurts. The naughtier amongst them are perhaps nibbling on a sugary indulgence in a highly-sexualised manner. Needless to say, this guilty pleasure will be something suitably delicate: perhaps a Flake or a Galaxy Ripple – certainly nothing as crude or calorific as a Mars bar.

On the whole, the gendered marketing of food is pretty effective. I know a few daring ladies who will brave a Yorkie bar, despite its ominous warning, but I can think of many more who can’t resist a small piece of Galaxy. When I think of friends partial to a Big Mac, it’s mostly males who spring to mind. But what exactly is the role of advertising here? Are there legitimate biological reasons for these stereotypes? Or does advertising play into centuries of culturally created notions of gender?

There is certainly an element of biology to it. Men, being larger on average, need more calories. They also have a naturally higher ratio of muscle to fat, which creates a tendency to burn off what they eat more quickly. There are also notable differences between male and female taste buds: about 35% of women are ‘supertasters’ compared to a mere 15% of men. Being a ‘supertaster’ means having a greater number of taste buds; flavours appear richer to the average ‘supertaster’, making spicy or bitter food a struggle. They also have a tendency to get full much faster than a ‘non-taster’. This could potentially explain the stereotype that women enjoy smaller portions. Yet this is a minor statistic, and on the whole there is little biological reasoning to be found behind the gendering of food. There is no scientific explanation for the supposed male propensity towards meat, nor does there appear to be any for the apparent female fondness for fruit and vegetables. In fact, the greater number of female ‘supertasters’ would indicate the opposite (it’s said ‘supertasters’ dislike green veg).

Gendered advertisements seem less the product of biology and more of socialisation. Socialisation contributes to the creation of stereotypes and occurs in large part through advertising. In 2015, ‘Social Psychology’ published a telling exploration into the extent to which people are affected by gendered advertising. Researchers presented 93 adults with identical blueberry muffins. Some had a typically ‘feminine’ label: a picture of a ballerina with the word ‘healthy’ below it, others a ‘masculine’ label: the image of a footballer with the word ‘mega’ beneath it and finally, a third section that sought to challenge typical stereotypes, some with ‘mega’ below a ballerina, and others with ‘healthy’ below a footballer. Results revealed that not only did people display a preference for the muffin that ‘suited’ their gender, they even went as far as declaring its counterpart tasted worse. The way a food is marketed, therefore, affects perceived taste. Researcher Luke Zhu explained, “people’s perceptions of food are so entrenched in gender stereotypes” that they are “confused and turned off by mixed gender alternatives”.

It would appear that the gendered way in which food is marketed influences us more than we realise. Yet, the issue remains: how can we overcome it? Would a rebellious bite of the ‘masculine’ Yorkie bar merely be playing into Nestle’s double-bluff? Is challenging the stereotype by buying a Coke Zero merely reinforcing the existing marketing binary in a new way? Perhaps if I really want to defy convention, I should embrace those copious quantities of sugar and stick to plain Coca-Cola…