ALI ADENWALA considers the role of borders in the last century of Middle Eastern geopolitics.

Across Upper Mesopotamia, running along the Hamad desert and cutting through the Euphrates like a scar, is a 600km frontier that makes up the Iraqi-Syrian border. It was here, in early 2014, that ISIS filmed one of their first propaganda videos. A shaky, handheld camera recorded a bulldozer running through a pit of sand, panning down to a piece of paper lying in the dirt, with the words, ‘End of Sykes-Picot.’ At the video’s conclusion, an elderly Arab man is seen rejoicing as tears of joy fall from the corners of his eyes.

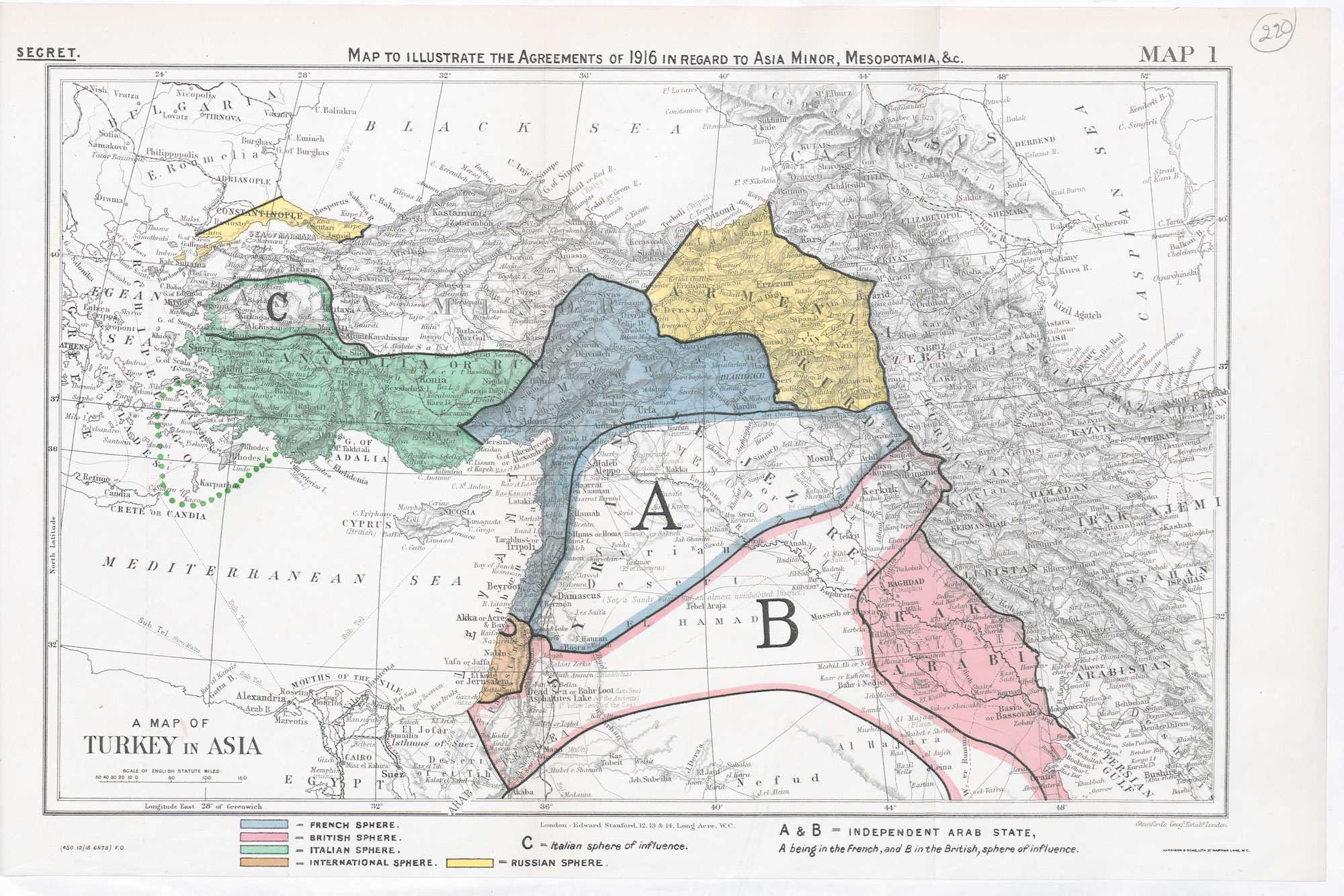

For too many people in the Middle East, the words ‘Sykes-Picot’ are recited with ominous, traumatic undertones. They refer to the secret agreement in 1916 between British politician Mark Sykes and French diplomat François Georges-Picot, which dissected the carcass of the Ottoman Empire, dividing its land between the two powers. The modern Middle East, then, is defined by this colonialist vision of arbitrary lines drawn on a map, then imaginatively written onto the earth, separating peoples, families, and clans and disregarding their national ambitions. Nowhere was this more true than in Iraq, as the British cobbled together three Ottoman provinces containing Sunnis, Shi’ites, and Kurds, cementing the political instability which was to come. When the Kurds rebelled against the British in 1920, in a struggle to gain independence that continues today, Churchill was quoted saying that he was ‘in favour of using poisoned gas against the uncivilised tribes’ in order to ‘spread a lively terror’. It is a cruel coincidence, then, that 68 years later Saddam Hussein did what Churchill himself first advocated, and it is clear that Hussein thought nothing of these lines in the sand when he invaded Iran in 1980 and Kuwait in 1990. Although historians disagree on just how much these artificial borders can be blamed for the region’s troubles today, the legacy of the Anglo-French colonial enterprise as a whole is undeniable: brutal puppet dictators, faked elections, cardboard institutions, and seemingly endless suppression.

We still live in an era where borders define the political landscape: Trump’s now infamous immigration ban, the Mexican-border wall, as well as Brexit’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and the grotesque stone barricade enclosing the Calais Jungle make this manifestly clear. However arbitrary they might have been at conception, Sykes’ and Picot’s borders (and their wider legacy) have also remained intractable. Supranational ideologies, such as pan-Arabism, pan-Islamism, Nasserism in Egypt and Baathism in Iraq, have failed, and so have other attempts at unification: Iraq and Jordan’s Arab Federation collapsed sixth-months after its conception, as did Syria and Egypt’s United Arab Republic. Gaddafi’s attempts throughout the 70s to merge Libya with the UAE, Sudan, and Tunisia were similarly futile. The borders that Arab nationalism threatened to sweep away have since remained.

Today we need to ask whether the unraveling of these borders is necessary, or even desirable. Parag Khanna believes that ‘the Arab world today is ripe for reorganisation’, but looking to the pre-colonial as a solution may open a Pandora’s box of ethnic-religious conflict and contradictory territorial claims. The only relatively successful method for dissolving borders seems to be through bloody, cataclysmic ruptures, as recent history has shown. The collapse of Libya, which unraveled Gaddafi’s old borders, facilitated the sale of his weapons to rebels in Syria and Egypt, and threatened the stability of neighbouring Tunisia. Meanwhile, ISIS’s goal to annihilate the Sykes-Picot Agreement and establish an ‘Islamic state’ under a single ‘caliphate’ has lead to the mass suffering of hundreds of thousands of people. Grand visions of ‘what could have been’ are, understandably, not easily corroded, but at the same time, distorting and romanticising the past is to violently threaten the future.

At an intrinsic level however, borders are hollow, meaningless constructions. They only have meaning when meanings are imposed on them by powerful institutions like the state and the military. When a state like Libya or Syria collapses, when its institutions crumble, so too does the concept of a ‘frontier’. To the millions of displaced refugees flooding into Europe, this concept is absolutely meaningless: when they choose to travel from Greece to Germany or to Sweden, they intend to walk, however many wired fences, police blockades, or tear-gas induced chokes it takes to get there.

The strengthening of Western frontiers in reaction to this is evidence enough of their symbolic power. To the West, borders perpetuate an illusion of security that makes a borderless world terrifying. Yet to others, especially those who don’t choose their borders, these lines in the sand do not represent stability, but rather a legacy of tyranny and suffocation that begs to be overcome.

Featured image courtesy of British Library