DAISY CLAGUE probes controversial instances of physical objectification.

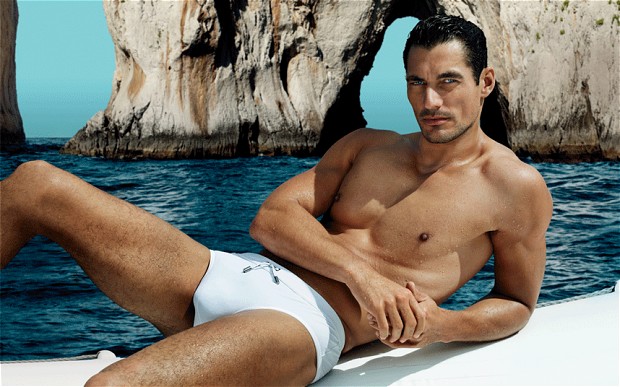

British women were in uproar earlier this year when Protein World asked if they were ‘beach body ready’: ‘If you don’t want to look at my body while I am at the beach, then I don’t care’ retorted angry Brits. The ads of a weight loss product picturing a bikini-clad model were considered so outrageous that they were banned in the UK. But present these same outraged women with a two-story billboard of David Gandy or the chiseled torso of Daniel Craig and many would be be jostling others out of the way to get a look in.

Why do so many British women talk about men in a way in which they would never want to hear women discussed? Is this idiom harmless, or does it reveal a double standard? And what does this have to do with feminism? ELLE magazine, creators of the ‘this is what a feminist looks like’ t-shirt, certainly threw this into question when they ran a ‘Magic Mike abs special’ on their Twitter feed. With regard to a double standard, this seems to be a case in point.

Reducing anyone to value only their physical attributes is reductive and undeniably disrespectful. Men may be newer to the experience of the opposite sex assessing their value based on their body, but this objectification is equally unjustifiable and wrong. In fact, by objectifying men, women arguably detract from the legitimacy of their own claims against female sexual objectification: cue the #meninists and their complaints about feminist hypocrisy. If, as Emma Watson tells us, women need men to join the feminist movement, surely we should be leading by example? Despite society’s increasingly aesthetic focus and the ease with which women can give tit for tat by ogling David Peckham’s package, some sort of SheForHe adaptation might be a better way to show men that we’re serious about saying no to cat-calling. We need to consider the impact of promoting a narrow male body image ideal: just as women struggle with media-induced pressure to be a certain weight and shape, so too do young men increasingly feel the need to turn their bodies into the broad-shouldered, eight-pack flaunting extreme that is the equally illusory masculine counterpart to emaciated female models.

In the real workplace, rather than billboards’ false simulation of reality, there is a difference between the physical objectification of women and that of men. Despite being the top box-office-grossing performer (male or female) of 2014, we found out from last year’s Sony email leaks that Jennifer Lawrence was being paid less than her male co-stars. A 2013 survey showed that just over one in ten women are experiencing sexual harassment in their jobs, (not to mention that the gender pay gap in this country has widened for the first time in five years). This is despite the fact that girls are outperforming boys at school and are more likely to attend university. Women have historically been valued in both public and private spheres based on their physical appearance far above other facets of their person; this evidence shows that what women look like is still being prioritised over how they think or what they can do. We still haven’t reached a point at which either sex can be valued based on merit and on the same terms.

Men, on the other hand, exist in a society that is built on and geared towards maintaining their supremacy. The gender ratio is vastly imbalanced in the White House, House of Commons, and boardrooms worldwide (yes, there still are more men called John in the FTSE100 than women). Objectifying men is evidently problematic, but it doesn’t seem to be damaging the power structures in their favour, nor detracting from how they are perceived overall: as competent, valuable, and authoritative. For many men, attractiveness is an add-on to whatever skills they have. For women, attractiveness is still ‘it’. Women are ridden with a binary identity: attractive or not? Upon entering a male sphere their competence and legitimacy is equated with their attractiveness. The first thing we heard about Michele Obama was that she has good arms. While Hilary Clinton and Angela Merkel negotiate the political sphere they are constantly lambasted for being ‘unattractive’. Serena Williams is criticised for being ‘built like a man’ as she threatens the male dominated world of athleticism with her numerous tennis achievements. When men are objectified, it doesn’t threaten their overall economic power or position in society; women are still in a more fragile position – objectification can really set us back. At the most extreme level physical objectification compromises women’s physical safety as well. Margaret Atwood said, ‘men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.’ When talking of the status of ‘men’ and ‘women’ it is impossible not to generalise; Atwood’s statement worryingly oversimplifies, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t contain pertinent and manifest truth.

Degrading men to the role of eye candy sends the message that we’re happy to live in a world where someone’s worth is decided by their sexual appeal. We don’t have equality yet, and male objectification won’t help us get to it. Nevertheless, as long as Ryan Gosling’s chest isn’t causing him to be paid less than his co-stars, be ‘shamed’ by leaked nude images or feel genuine fear when he’s walking dark streets solo, I don’t think he can complain too much.