Zsofia Paulikovics explores the power of fangirldom.

During a recent gig, Harry Styles performed ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ by One Direction, a hit single from the band of which he was the frontman until their separation in 2016. He has barely touched his guitar before the crowd erupts into a collective female scream; by the chorus, the audience is almost louder than Styles; by the second verse he’s stopped singing, and stands on stage, smiling and listening. He looks touched but not surprised. A month before the release of his first solo album, Styles gave an exclusive interview to Rolling Stone. When the interviewer asked him whether he struggles to prove his credibility given that a large percentage of his fans are young girls, he gave an impassioned answer:

‘Who’s to say that young girls who like pop music – short for popular, right? – have worse musical taste than a 30-year-old hipster guy? That’s not up to you to say…Teenage-girl fans – they don’t lie. If they like you, they’re there. They don’t act ‘too cool.’ They like you, and they tell you. Which is sick.’

Following his separation from One Direction, ex-member Zayn Malik also commented on the idea of coolness, famously admitting that One Direction’s music was not quite to his taste. ‘If I was sat at a dinner date with a girl, I would play some cool shit you know what I mean? I want to make music that I think is cool shit’. Zayn’s solo trajectory has seen him move decidedly away from pop: the songs in his first solo album, Mind of Mine, are mainly R&B and hip hop, and have a darker, more nuanced sound – at least relative to One Direction’s sugary hits. Liam Payne might have had a similar motivation behind his first solo single ‘Strip That Down’. His sound is not a radical break from his pop background, but the single is decisively different from his previous band, which he himself references: ‘You know, I used to be in 1D (now I’m out, free) / People want me for one thing (that’s not me)’. The sort of ‘coolness’ that Malik and Payne lust after is very different from that described by Styles. They appear embarrassed by their boyband past, eager to disown it and progress on to a more adult, reserved sound. By distancing themselves from their old music, they simultaneously distance themselves from the young women who fell in love with their records. Styles does the opposite – he embraces it, welcoming his adoring young female fans back into the fold in the process.

This is not to say that Zayn is unaware of his fans. In his 2016 interview in The Fader, Zayn asserts that he does not think his fans, some of whom attempt to enter his property, are crazy – just ‘passionate’. His audience, more so than any of his former bandmates’, is important because it is intersectional. Zayn was not just the only person of colour in One Direction, but, as he says in the Fader story, the ‘first of his kind’ as a mainstream Muslim boyband member. Many of his fans are Muslims and/or people of South Asian descent, most of them young women and girls. Malik has expressed reluctance over the idea of being a role model and speaking out on issues specific to the Muslim community. But the power of fandom is that Malik doesn’t have to be especially vocal about his religion and background for his audience to see themselves in him. As the writer, co-host of the Two Brown Girls podcast, and self-proclaimed ‘foremost Zayn Malik scholar’ Fariha Róisín has stated, simple gestures of faith such as the singer’s yearly Eid Mubarak message on Twitter are important because they provide a glimpse into the life of a young British Muslim, for whom religion is as ordinary as making music or getting tattoos. Even the intermission song ‘fLoWer’ on Mind of Mine is sung entirely in Urdu: a musical nod to Malik’s heritage.

Young female pop rock fans, like the audience of One Direction, are often characterised as a group by a naive jouissance: a kind of innocence that remains largely unafforded to young women of colour or Muslim women. Through the prism of whiteness in the music industry, young female music fans of colour are often hypersexualised or branded as ‘baddies’, while Muslim girls are frequently viewed as objects to be freed, who lack autonomy or secular interests. Regardless of whether Zayn himself is outspoken, there is power in the visibility of his fandom, in his fans seeing each other and being seen by the wider music community.

A ‘cool’ girl is beautiful, unattainable and effortless; a ‘cool’ girl is desired more than she desires – or if she does, she does not show it. Fans and teenage girls – let alone teenage girl fans – are the antithesis of this typical definition of ‘cool’. Fandom has no chill: it is a visible, audible manifestation of love and desire with little expectation of reciprocity beyond the object of fandom liking a tweet about them or following a fan account on Instagram. Fans will dedicate time, energy and money to their favourite musician, an act that often becomes less about the star and more about proving loyalty and dedication to themselves and their peers. In a 1964 essay in the New Statesman entitled ‘The Menace of Beatleism’, Paul Johnson reflects on Beatles fans, stating that at 16, he was reading ‘the whole of Shakespeare and Marlowe’ and listening to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. ‘Are teenagers different today?’ he asks? ‘Of course not. Those who flock round the Beatles, who scream themselves into hysteria, are the least fortunate of their generation, the dull, the idle, the failures…’. Johnson went on to become an editor at the New Statesman, and the article became the most complained about in the history of the publication. The statement sounded snobbish at the time; today it reads as downright anachronistic and sexist.

As with all subcultures, the internet has allowed fan tribes to migrate online and form global communities. Different tribes have their own moniker (Directioners, Arianators, the Beyhive); they have their own vocabulary and language, as well as expansive social media communities. The female gaze thrives in these online communities, because the fangirl’s creative agency is entirely unaffected by real life and its patriarchal order. Fangirl communities are spaces free from the claustrophobic male gaze; they give young women space to breathe together without being looked down on in a Johnsonian way.

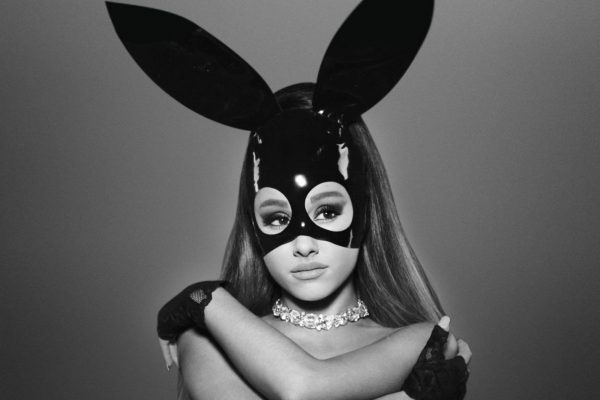

Fan girls are a uniquely sniggered at demographic by older, male music critics. Ariana Grande, a former Disney star turned pop singer, is often on the receiving end of this criticism, despite her undeniable talent, which is acknowledged even by her harshest critics. But unlike Styles, Ariana also elicits critique because she herself is a girly girl, with her long, high ponytail, bunny ear headbands and exaggerated doe eyes. Nothing illustrates this prejudice better than the internet’s collective surprise at Grande having organised a high profile benefit concert in Manchester (in under two weeks) for those affected by the recent terrorist attack. The show, entitled ‘One Love’, featured a high profile line-up that included Justin Bieber, Miley Cyrus, Pharrell and Liam Gallagher, and it was a clear demonstration of how well Grande understands the significance of her fan community. A choir from Parrs Wood High School performed on stage and Grande let them shine, only joining in occasionally. Between acts, she spoke about meeting fans and the families that lost loved ones in the attack. ‘I had the pleasure of meeting Olivia’s mummy a few days ago’ she said, referring to 15 year-old victim Olivia Campbell, whose mother’s desperate search for her daughter was widely shared on Twitter. ‘She…said Olivia would have wanted to hear the hits’. Ariana Grande was underestimated by the mainstream, chauvinistic media. Piers Morgan publicly lambasted Grande on twitter for cancelling her tour and returning to the US, rather than staying to meet the victims and families affected by the attack (which she eventually did do). Though Morgan later retracted his comments and apologised in the wake of Ariana’s stellar benefit concert, his initially dismissive response is indicative of the reductive view of women held by a large proportion of right-wing male journalists: Paul Johnson and Piers Morgan have much in common.

Fandom is always a fantasy. When fangirls are dismissed as dumb, it is done with the sexist assumption that they are unable to separate imagination from reality. Most fangirls, though, are well aware of the line separating the two – they simply choose to step into a world where they are met with recognition, rather than ridicule. Fan communities are spaces of self preservation for marginalised groups. They are a source of momentary liberation for young female fans of colour, who are often dismissed by the white, masculine music industry; they are spaces free from judgment, free from ‘coolness’. There was nothing self consciously ‘cool’ about the One Love concert either – people danced, laughed, sang and cried together. But I doubt any of the fans in the audience cared the least bit about anyone’s opinion.

Featured image courtesy of www.dailymail.co.uk