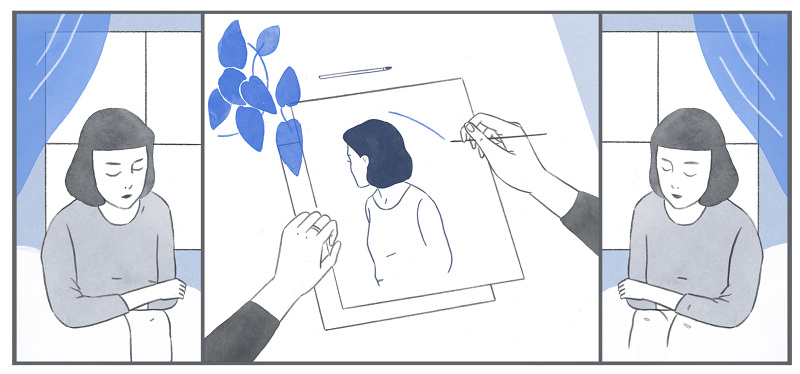

LUISE YANG examines the artist’s sense of privacy in the short fiction of YiYun Li.

‘Privacy Please’ is a powerful phrase, evolving out of the original ‘Do Not Disturb’ hotel sign into a command that requires no verb. Today we use the word ‘privacy’ to separate public life from private life, establishing our own individual boundaries. After Edward Snowden’s exposé of the NSA’s extensive phone and internet surveillance in 2013, we have become increasingly concerned with how other people can access and use information about us. We possess what The New Yorker’s archive editor Joshua Rothman calls, the ‘citizen’s sense of privacy’.

Rothman writes that there is also the ‘artist’s sense of privacy’, and explores this in the case of Virginia Woolf. Clarissa in Mrs. Dalloway ‘prefers austerity to intimacy’. Choosing a lover between Peter who is determined to know her ‘soul-to-soul’, and Richard who ‘lets her soul remain her own’, Clarissa rejects as ‘intolerable’ the kind of intimacy which society encourages her to pursue. Instead she believes that,

‘there is a dignity in people; a solitude; even between husband and wife a gulf; and that one must respect. One would not part with it oneself, or take it, against his will, from one’s husband, without losing one’s independence, one’s self-respect—something, after all, priceless.’

This reflection illuminates Woolf’s own conception of privacy as ‘a gift that you’ve been given, which you must hold onto and treasure but never open’. Woolf’s presentation of inner solitude contributed to an era which oversaw profound changes to the lives of women, described by the writer Alice Munro as ‘the great switch’.

When I read Yiyun Li’s contemporary short stories, I perceive echoes of Woolf in the women that Li creates. In Li’s debut collection, A Thousand Years of Good Prayers, we are introduced to Granny Lin, who makes the ‘wise choice’ for an older woman: becoming wife to a seventy-six-year-old mute with Alzheimer’s, who doesn’t recognise her and ‘will die in no time’. Despite the silent and non-invasive nature of their relationship, Lin craves solitude. Her favourite aspect of married life is the bathroom. After a life spent in public bathrooms where exposed bodies fought over the ‘lukewarm water drizzling from rusty showers’, Granny Lin never misses a chance to use the private bathroom. This makes sense to me. I imagine Granny Lin doing everything and nothing in the bathroom; she is simply enjoying her inner solitude. The private bathroom is a space into which neither the writer nor the reader are privy.

In her latest story, A Sheltered Woman, Li introduces Auntie Mei, the ‘gold-medal nanny’. Auntie Mei has only one rule: she leaves a family’s house when the baby turns one month old. Auntie Mei finds her inner solitude, not in a private bathroom, but through the windows of her clients, which allow her to enjoy views ‘that did not belong to her’. Auntie Mei does not have children, and this separation makes her successful at her job. She does not want to know anyone; not her husband, and not the 126 families who are only names recorded in her notebook. For Auntie Mei, to be known is to be ‘imprisoned by someone else’s thought’. Extending even to self-knowledge, Auntie Mei leaves herself ‘undescribed, unspecified, and unknown’ to herself. Inner solitude is employed as a barrier which protects others and herself, ensuring that ‘no one in this world would be disturbed by having known her’. Reframing Woolf’s concept of privacy, YiYun Li asserts that ‘there is no final, satisfying way to balance our need to be known with our need to be alone’.

Interviewers tend to ask Yiyun Li variations of the same question: what is her relationship with China? Li consistently replies that she has two Chinas: the first she loves because it is filled with people trying ‘to lead serious and meaningful lives’; the second she does not love because it is a country ‘made rich from corruption and injustice’. Li was born in Beijing in 1972. Leaving China in 1996 to pursue a career in medical science, Li abandoned a doctorate in Immunology to enter the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Now she is a writer, and a Professor of English rated by her students as ‘inclusive’, ‘funny’ and ‘generous with her knowledge’, The New Yorker has named Li as one of the top twenty writers under forty, and she has won awards including the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, and the Guardian First Book Award. YiYun Li is often cited as the Chinese success story of the American Dream, and although interviewers enjoy emphasising its influence on her, Li is skeptical of being characterised by this archetype.

Viewed by many as ‘the dreamer’, YiYun Li writes that this is the ‘last thing she wants to be called, in China or in America’. Growing up in Beijing, she recalls becoming ‘especially sensitive’ to how ‘people have power over others’. In a similar way to the ‘gold-medal nanny’, Li is not so much a dreamer as a protector of inner solitude; of hers, her characters, and yours: the reader. Whatever hides behind her reticence has the right to stay hidden. These days we can use Twitter or Instagram to form tenuous connections with strangers. I know Li’s e-mail address, and could sit in front of her teaching office until she feels obliged to meet me. But I’m not going to do that. I respect her inner solitude, and am almost afraid that if we met, our two solitudes would not mix, and I would leave feeling alienated and frustrated. So for now, I am happier, and I imagine Li is too, that I’m reading and feeling her works from a distance; respecting the artist’s request for ‘privacy please’.

‘A Thousand Years of Good Prayers’ is published by Harper Perennial (November 2006).