JOE KENELM reviews A Modest Little Man at The Bread and Roses Theatre.

Given Clement Attlee’s passion for the sport, it is perhaps cruel that he was actually once likened to a cricket ball: the higher he rose, so it was said, the more elusive he became. This notion of the former PM is typically orthodox: a vision of Attlee as kind, reliable, and bland. Eclipsed by larger government personalities, uninspiring in leadership, and muted in speech-making. Hard-working in cabinet, hard work in conversation.

In his brilliant biography Citizen Clem, John Bew argues for quite a different Attlee: ‘passionate, patriotic, ethical, and visionary.’ An MP for Limehouse during the party’s near annihilation in 1931, Attlee was a central figure in its gradual recovery. He was elected leader in 1935, brought the party into a war-time coalition with Churchill in Britain’s darkest hour and, in 1945, won an overwhelming mandate to carry out the most radical manifesto ever presented to the British electorate. Amounting to ‘no less than a new social contract between the individual and the state,’ it was a manifesto that would transform Britain for ever.

This is the figure who is revealed in flashes in this Francis Beckett’s biopic play, A Modest Little Man. In his wife Violet’s words: ‘Clem had passion.’ Towards the end of the show, asked what career he might have otherwise pursued, Attlee replies ‘poet’. It is a telling moment. Violet has already read out his response to a letter from a young girl named Anne, in which he explains to her—in rhyming couplets—that he cannot answer her query, but that he will pass the letter on to his education minister. Humble, and playful—both qualities underpin the closing lines of the play, a genuine Attlee limerick:

Few thought he was even a starter.

There were many in life who were smarter.

But he finished PM,

A CH, an OM,

An earl and a Knight of the Garter.

For a play with a famously reticent protagonist, A Modest Little Man is surprisingly funny. Interviewed by a grandiloquent journalist, Attlee is asked if he would like to elaborate on his answer ‘Nonsense’—‘Utter’, he responds. Frustrated with his non-committal, monosyllabic responses, King George VI asks Violet if she minds when he grunts. ‘I like it,’ she answers, ‘it reminds me he’s here.’ Narrating much of the play, Lynne O’Sullivan stands out playing Mrs Attlee as devoted, gentle, and steely in equal measure.

Steven Maddock as Morrison buzzes about his party leader, oily and treacherous, in a perpetual state of condescending disbelief. Silas Hawkins as Hugh Dalton is fawning, slippery, and verbose: the perfect Old Etonian. Clive Greenwood as Nye Bevan, Ernie Bevin, King George —not to mention a vicar—inflects his way the length and breadth of England, always with panache.

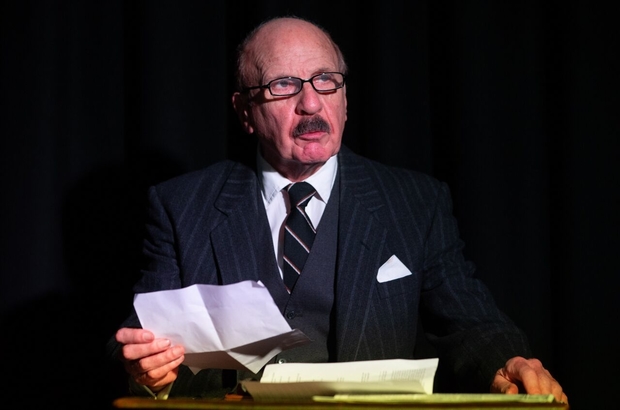

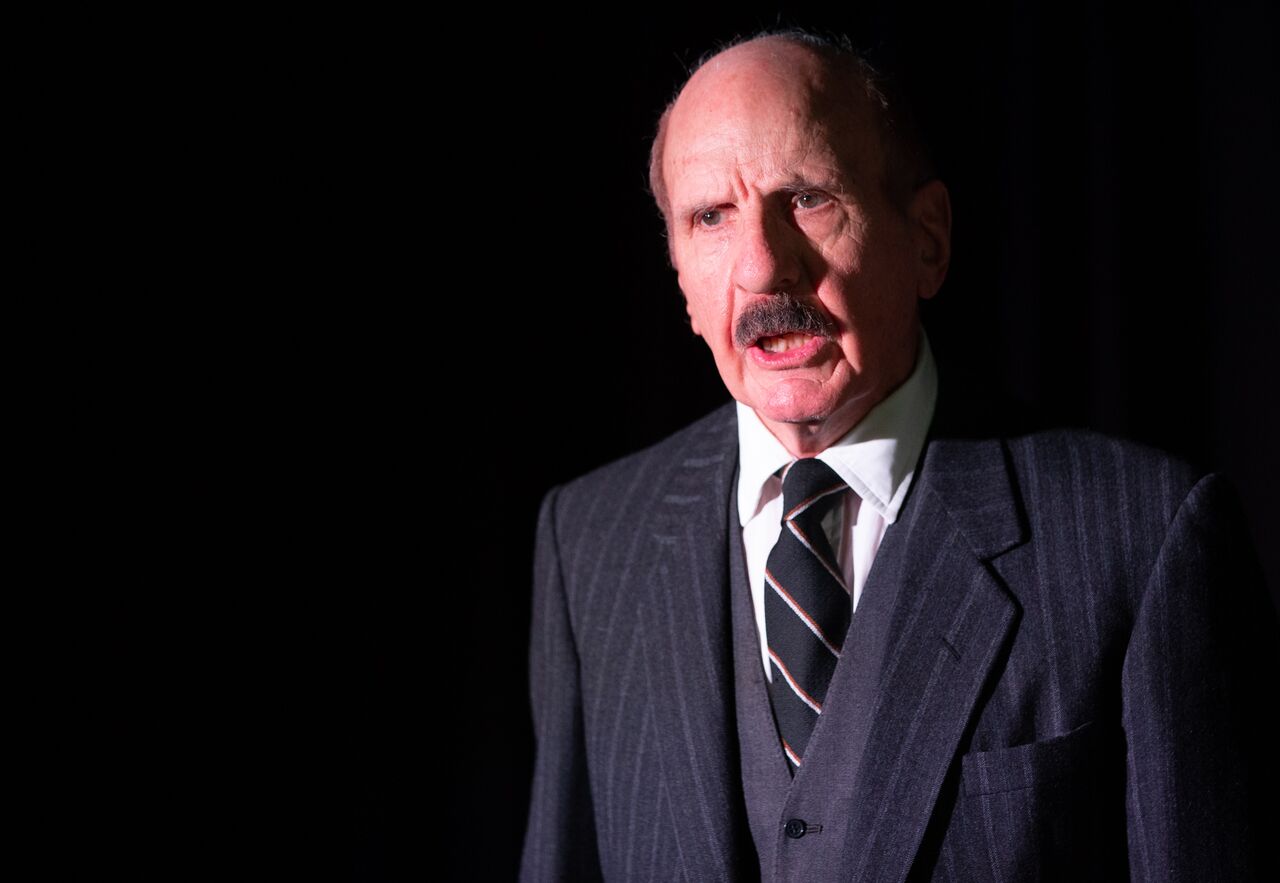

Roger Rose’s Clement Attlee is the pivot. Asked to deliver a speech from the stump in Stepney, the Prime Minister is as flustered as he is quietly controlled when—after a long debate over whether a vitriolic speech should go ahead—he enters and conclusively instructs Bevan ‘Don’t do it. No good.’ He is incisive, and a figure of absolute integrity. The contrast between Attlee and some of his cabinet could not be more pronounced. The political message is clear.

Beckett’s script, the first, he says, to place Attlee centre-stage, is punchy, covering a good deal of ground: from Haileybury school to Buckingham Palace, Stepney to Downing Street. Very occasionally the scenes drag, in need of a little Attleean pith, and the production could do with a little more time devoted to the lovely dynamic between Rose and O’Sullivan.

Yet this is a charming and hopeful production, and it ends fittingly. Attlee reminisces delightedly about English cricket—Hutton, Washbrook, and Wally Hammond. Morrison bursts in and reveals that the nationalisation program can begin. Bevan triumphantly announces the establishment of the NHS. Elusive Mr Attlee may have been: rise high, he certainly did.

A Modest Little Man runs at The Bread and Roses Theatre until 26th January. Find more information here.

Featured image courtesy of Mark Thomas.