FRANCESCO D’ALESSIO reflects on the burial crisis and identity loss in the contemporary city.

Cemeteries and graveyards resemble cities and villages. Graves are like buildings and the space around them like streets. When walking through a cemetery, we may even think the same things that we think in cities. Rem Koolhaas, for instance, writes in S,M,L,XL (1995), ‘Now that I have grown old, I have the feeling, when walking through a cemetery, that I am apartment hunting.’

The cemetery is everyone’s future city. As with any city, its identity is not static and its existence not safe. Our right to it is not to be taken for granted; it greatly depends on financial and social status. Throughout history, the architecture of cities and cemeteries have evolved and adapted to the demands of an ever changing culture. As of today, we are at a standstill, and just like the modern city, the cemetery is facing significant issues too, such as overcrowding and lack of space.

Anyone who moves to London is most likely familiar with the frustration of struggling to secure some sort of affordable accommodation: given the city’s saturated urban fabric and the population increasing on a daily basis, it is challenging to find an available room, let alone an affordable one. Anyone who dies in London faces very similar challenges in the cemetery. After all, if there’s not enough space for us in the city whilst we’re alive, how can there be enough space for us when we’re dead and we matter even less?

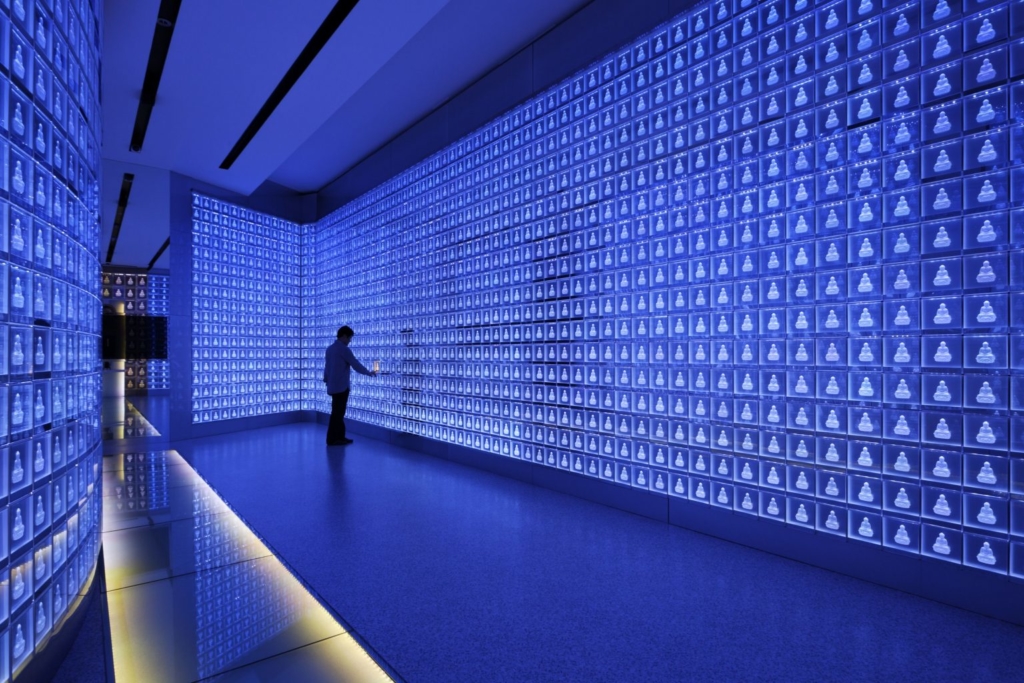

Culturally, we have always insisted on a peculiar mode of reverence for the dead, materialised in the traditional cemetery. In times of crisis, when sustainability becomes the utmost priority, we may need to question whether it is still feasible to demand that after we’re gone, a new physical space in our honour is preserved permanently, despite an increasingly depleting environment and congested cities suffocating their living inhabitants. Although a great number of people choose to be cremated – in the UK this figure is around 80 percent – many cremations still result in burial. Approximately 150,000 new graves are created every year in total, not including the urns stored in columbariums and other above-ground structures in the cemetery: a testament to the undying demand for physical space dedicated to the dead, which now faces a crisis.

Studies predict that in less than 20 years, city cemeteries will be completely full, meaning that no more virgin plots will be available. Getting rid of existing graves to make space for the new currently seems to be the most favoured solution to the burial crisis in the UK. When walking through a cemetery, with this idea in mind, you may begin to question whether you could end up replacing the burial spot of this or that person. You may find yourself fantasising about who will replace your spot once enough decades of residence have elapsed. What’s going to happen to your remains when they get displaced? After years spent moving from flat to flat and job to job, as a young person with little hope of ever settling down, it is amusing to realise that even in death the destiny you’re presented with is just as uncertain, and your identity just as precarious. What ever happened to ‘rest in peace’?

Grave recycling may be the easiest solution to the burial crisis, but an increasing number of designers and activists around the world have begun to explore how else the future cemetery could evolve in the future. A fascinating array of ideas already exists, ranging from skyscraper cemeteries and green burials to offshore death islands and digital graveyards. Having said that, we still need more engagement, and more innovative, feasible solutions that are suitable to our epoch.

The adaptation of the cemetery in relation to the growth of the city is not a new issue by any means. Designers have engaged with the evolution of the cemetery in every transitional moment of modern history, consistently employing their macabre creativity. Take, for example, the Hardy Tree: an ash encircled by hundreds of wretched gravestones in St Pancras’ Old Churchyard. Originally, these gravestones were neatly located nearby, but to make space for the expansion of the railway in 1865, the churchyard had to be resized. It is said that author Thomas Hardy came up with the bizarre solution of cramming the graves into a ring embracing the tree next to the old church, thus saving them from destruction. In the satirical poem The Levelled Church (1882) Hardy envisions conversations between the dead residents of the site: they lament that they are ‘mixed to human jam’, that their identity is compromised. They exclaim to each other, ‘I know not which I am’. This grotesque poem from the Victorian era still captures so well the sense of identity-vulnerability inevitably shared by those who inhabit the indifferent, overgrown contemporary city.

The state of the city and that of the cemetery always reflect each other, as well as reflecting the value that society gives respectively to life and to death in every given historical period. The preoccupation of man with housing and burying, beyond being merely a response to the primitive necessity for shelter and riddance, really is a pledge to the affirmation of identity. As modernity exacerbates indifference toward identity, institutional preoccupation with housing and burying decreases, while the impetus to affirm identity becomes stronger in the individual, whose reaction will be epitomised by their unsolicited mark on the city. Every time we subtly appropriate the city and change something around – make art, write poems, write on walls, record music, publish zines, build things or break things – we are compensating for our vulnerable houses and graves, by transmigrating our identity to a new allegorical home as well as letting the content of our art be our epitaph. Art does not lament ‘I know not which I am,’ though its content can. Art transcends identity. It is unafraid of anonymity. It bestows the individual who is lost in the city with a new sense of belonging, alternative to the home, and their identity with a promise of permanence, alternative to the grave.

Featured image courtesy of flickr.com.