MICH ROSSITER reviews Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life at The Design Museum.

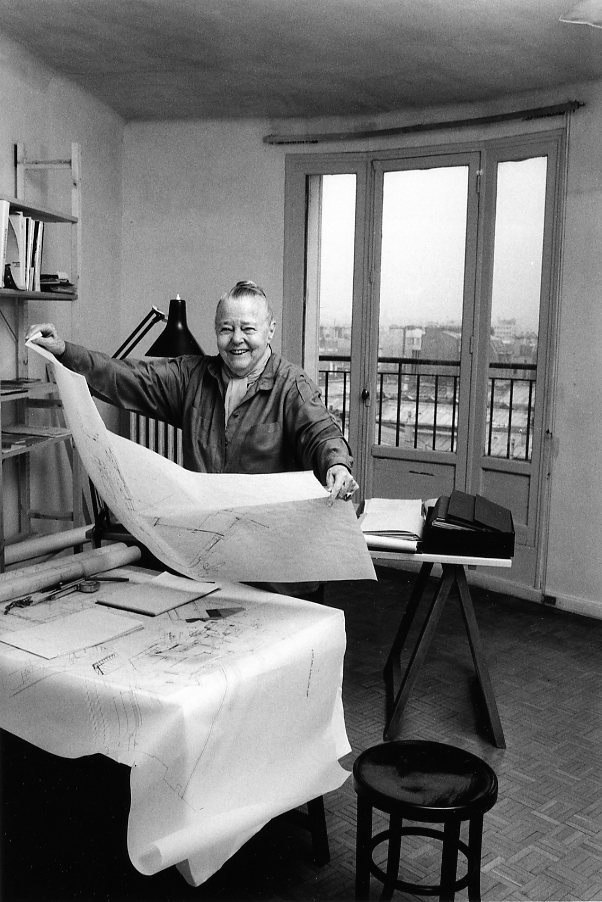

Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life is an expansive and overdue celebration of this unsung defector of modernism. Perriand’s success derived from her ability to acquire many diverse, contrasting design philosophies and condense them into new ways of thinking. A career which spanned much of the 20th century, in which Perriand explored how the human body could connect with material qualities and political aims, is sequenced across five key spaces.

The exhibition’s opening chapter sets the scene for Perriand’s first foray into furniture design: Perriand as a talented young designer working at the Paris studio of Le Corbusier, Europe’s famous (and indeed, infamous) flag-bearer for modernism and advocate for the design of homes as ‘machines for living’. Perriand’s early commitment to designing for the Machine Age is manifested in her iconic ball bearing necklace, through which she kept modernism close to her chest.

An important piece from this early period is ‘chaise-longue basculante’ (1928). The work is pneumatic, elegant and adaptable, transforming into a rocking chair when lifted from its cradle and placed on the floor. It embodies the intellect behind Perriand’s work and the more positive aspect of modernism’s grand plan: design simplicity, seventy years before Steve Jobs adorned himself as its messiah.

The show presented a stimulating variety of material. Finished works of furniture and interior spaces are accompanied by concept sketches, patent and technical drawings, intimate photos of Perriand’s daily life, design models and curious artefacts which Perriand used as design inspiration. In bringing all these together, the exhibition delivered a richness of content whereby items supported one another and built a cohesive bigger picture of Perriand’s achievements.

The exhibition also documents Perriand’s defection from modernism to a more material-focused method of working in the 1930s, the designer driven by a fascination with objet-trouvé and biomorphic design. However, in this section, the changing economic and political values in Perriand’s work, which moves from empowering machines to empowering people, is largely brushed over. Curators took a curiously apolitical stance here, and again when detailing Perriand’s work with anti-fascist activists in Spain. In removing this key aspect from her work, Perriand’s political mettle was lost in translation.

The exhibition did well to avoid lazy or fetishistic stereotyping of Japan’s design traditions. Perriand’s relationship with Japan was unpacked sensitively and at length, conveying her collaboration with Japanese designers rather than presenting Japan as her muse. Even so, the exhibition failed to highlight the influence of Japan on its own design, which leant heavily on Japanese motifs, including accentuated shadows and paper panels. Furthermore, this chapter in the show was over-saturated with work, taking away from many of the important, highly-resolved climax-pieces.

Among these works are cantilever bamboo chair (1940) and bamboo and wood chaise longue (1940). Light and dynamic, these objects are comprised of sinuous, repeated, steam-bent bamboo elements held by a more muscular frame. They embody the synthesis of Perriand’s eclectic inspirations and her masterful joining of dots between multiple strands of research. Had replicas of these chairs been provided to visitors, a more profound and corporeal understanding of Perriand’s evolution would have emerged. But this was not the case. In fact, the majority of Perriand’s work was not available to be used by the audience. Indeed, the most engaging and surprising part of the exhibition was the space in which replicas of Perriand’s work were arranged freely to be perched on and inhabited.

When asked about how one of Perriand’s 1920s modernist chaise-longues felt, one visitor replied that ‘it feels like being at the dentist’. This tongue-in-cheek comment points to a disappointment I had with the exhibition overall: the only works lent to visitors to feel, weigh and sit in for themselves were those which Perriand made in her modernist period under Le Corbusier, her ball bearing necklace still around her neck. Visitors therefore left the retrospective having seen the breadth of Perriand’s work, but having felt only her most mechanical.

At times, the exhibition’s infrastructure limited the power of Perriand’s work. The exhibition attempted to isolate Perriand’s designs rather than allow them to interact with the rest of the museum, which itself uses interpretations of modernist principles; this was a greatly missed opportunity. Another disappointment was the use of cumbersome low walls in front of reconstructed spaces, cynically barring visitors from being near the works.

Furthermore, one of the exhibition’s biggest shortcomings was its accessibility. Prices were steep: student and concession tickets cost nearly three times those sold at the Tate galleries and at the Barbican. No reproductions of Perriand’s work were available for purchase due to copyright technicalities, unless you bought a £25 catalogue. This restricted accessibility to the show reveals at best a lack of awareness and at worst an intentional exclusion of those without the means.

A final improvement for the show would be to have capitalised on Perriand’s relevance in the 21st century. As the internet-of-things grips our daily lives, and our mass-produced quotidian tools become more alien to us by the year due to their unfathomable fabrication and synthetic materials, arguably Perriand’s design principles make more sense now than ever. With British living rooms having shrunk by a third since the 1970s, Perriand’s domestic spaces are surely all the more powerful.

‘The Modern Life’ gave Perriand’s achievements and multiplicity space and time to breathe without simplifying her philosophy. An astonishing career was fleshed out with a strong inventory of works and an exciting juxtaposition of ideas. However, the failure to capitalise on the relevance of Perriand’s designs to pressing contemporary issues, such as the provision of high-quality housing and responding to the climate crisis, demonstrates a disconnect between the exhibition’s intentions: the Design Museum chose to stage an apolitical high-design show, in turn relegating its potential to pose important questions about how our built environments are made.

For those who couldn’t get enough of Perriand or missed the exhibition completely, ‘Noguchi’, the Barbican’s exhibition of the Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi, has recently opened and could act as a perfect follow-up to ‘The Modern Life’ – Noguchi and Perriand worked extensively together and their influences on each other’s work is palpable.

‘Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life’ was shown at The Design Museum from 19th June until 5th September 2021. ‘Noguchi’ is open at the Barbican Centre from until 9th January.

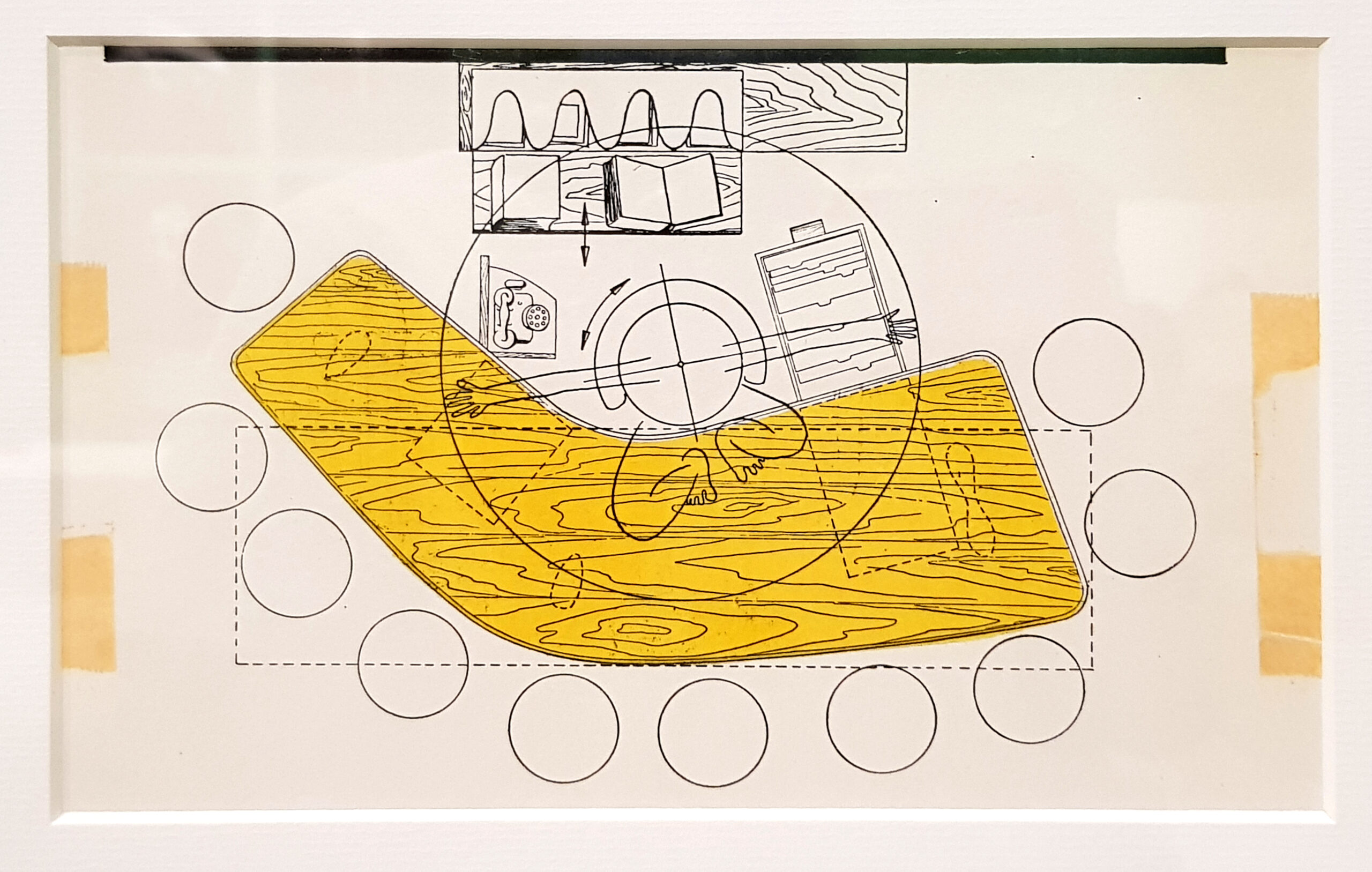

Featured Image: Ergonomic drawing of boomerang desk (1938) by Charlotte Perriand. Image courtesy of Mich Rossiter.