RUBY ANDERSON explores the feelings of frustration and bewilderment caused by Bridget Riley’s Op Art.

The experience of looking at a Bridget Riley painting is one of frustration; a frustration at the sheer indecipherability of these paintings. I do not mean this in the sense that these paintings occupy some sort of higher intellectual plane, their content incomprehensible. If anything, the works are painfully self-aware of being nothing more than mere geometry on the surface of a canvas. Yet, every work of Riley’s I have ever laid eyes on seems to do the antithesis of what paintings have been trying to do for centuries: they do not encourage a long, contemplative process of looking, but rather force the viewer to look away. Riley’s works implicate the viewer. You become so frustrated at the instability of this surface that you must abandon the work, give your eyes a rest – believe me, the strain of focusing one’s attention onto these ever-shifting planes is a sensation felt on a muscular level.

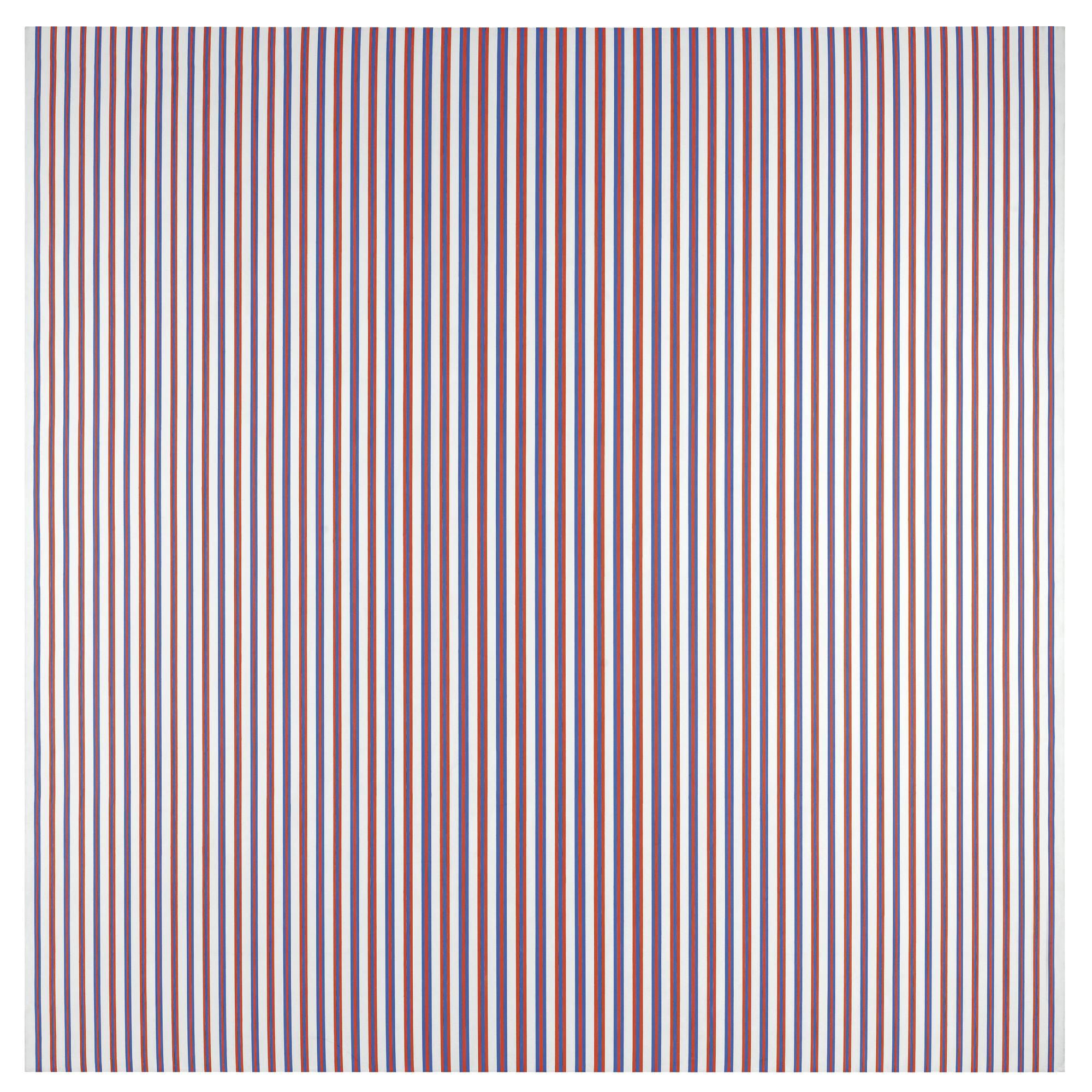

The basic components of Riley’s works are simple and theoretically comprehensible. Chant 2 (1967), for example, is composed of just two colours, red next to blue followed by blue next to red, characteristically separated by bands of white, like many of her other coloured ‘stripe’ works. The width of the coloured bands increases as they move closer to the centre of the canvas. Such a description feels formulaic, mathematical even, but nonetheless digestible. Yet, when looking at the canvas, slowly a new chromatic effect begins to confound the senses. An intangible spectrum of colour is created along the edges of these stripes. This may give us an indication as to why Riley’s canvases are so enormous – the longer the edge, the greater the propensity for optical fusion.

There is a shock factor inherent to Riley’s works – an inanimate object, something one could numbly saunter past on a lazy Sunday in a gallery, suddenly engages in a conversation with the viewer. Not only is this object inanimate, but it is also completely non-representational. There is no narrative or sense of dialogue to engage with, yet these images appear to move, seemingly without beginning or end, and in turn, move you; they are in a state of perpetual fluctuation, meaning the viewer is also. When you shift your gaze to focus on the motion in one region, it stops before your eyes yet commences in another, detectable in your periphery. The viewer is in competition with these inanimate objects, playing a game of cat and mouse, trying to catch a glimpse before the paintings once again shift. Yet we are always one step behind. I think the height of my frustration stems from my knowledge that the canvas no longer moves when I turn my back from it, but that I will never be able to observe the work in this static condition. Essentially, what the viewer sees is not what is painted on the canvas before them; an exhibition of Bridget Riley is more an exhibition of an optical effect than it is an exhibition of tangible objects.

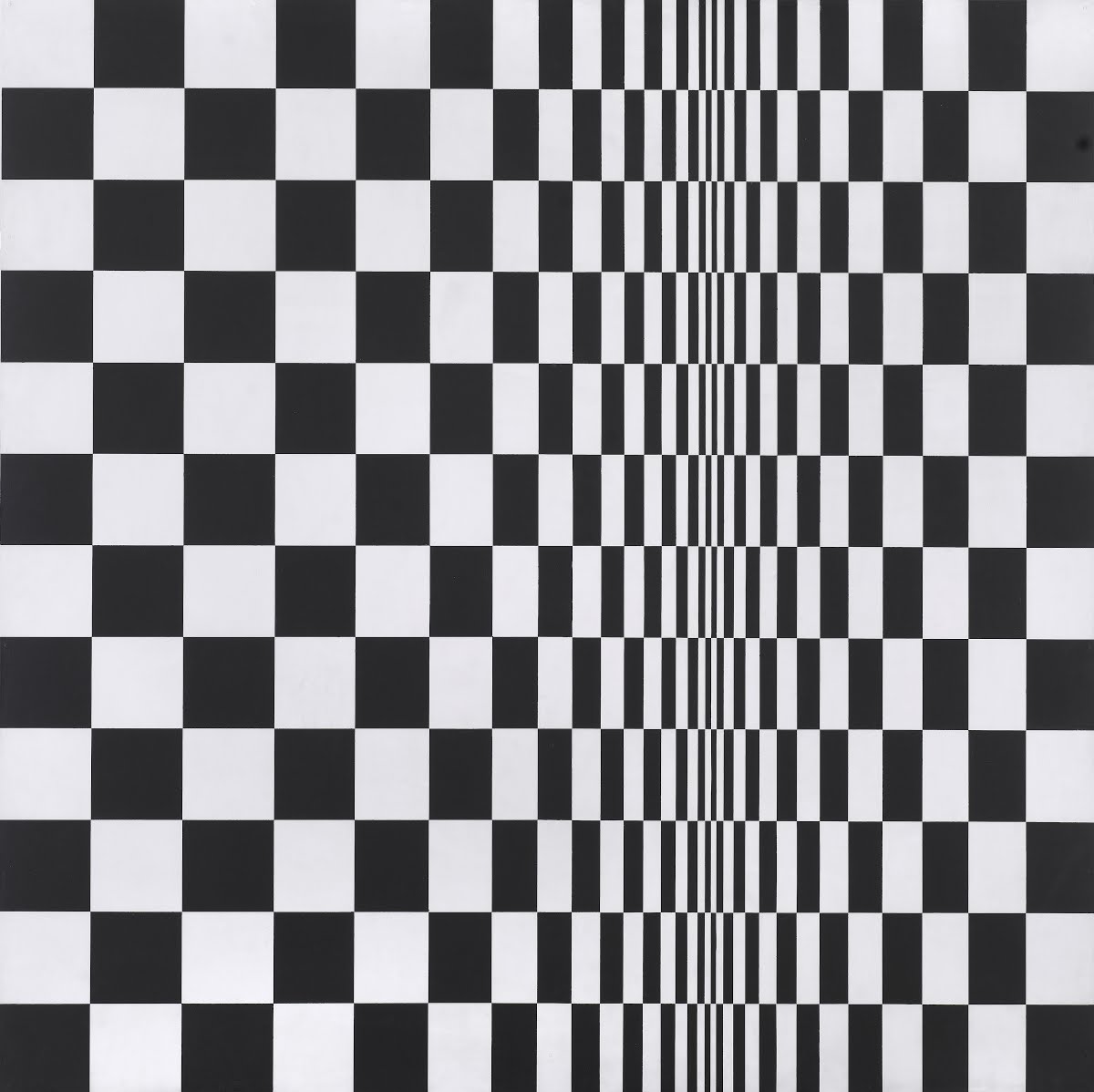

Riley’s black and white works are frustrating to the point of being nauseating. In Movement in Squares (1961), there is a buckling effect at the point where the black and white units are most tightly clenched together; Riley said of this work ‘everyone knows what a square looks like and how to make one on geometric terms’. Once again, my frustration stems from the fact that I feel as though I should be able to comprehend something as static and elementary as a square, yet I fail to do so. Comprehensible units have lost their individual identity; they are now one unified body that works in simultaneity to trip me up.

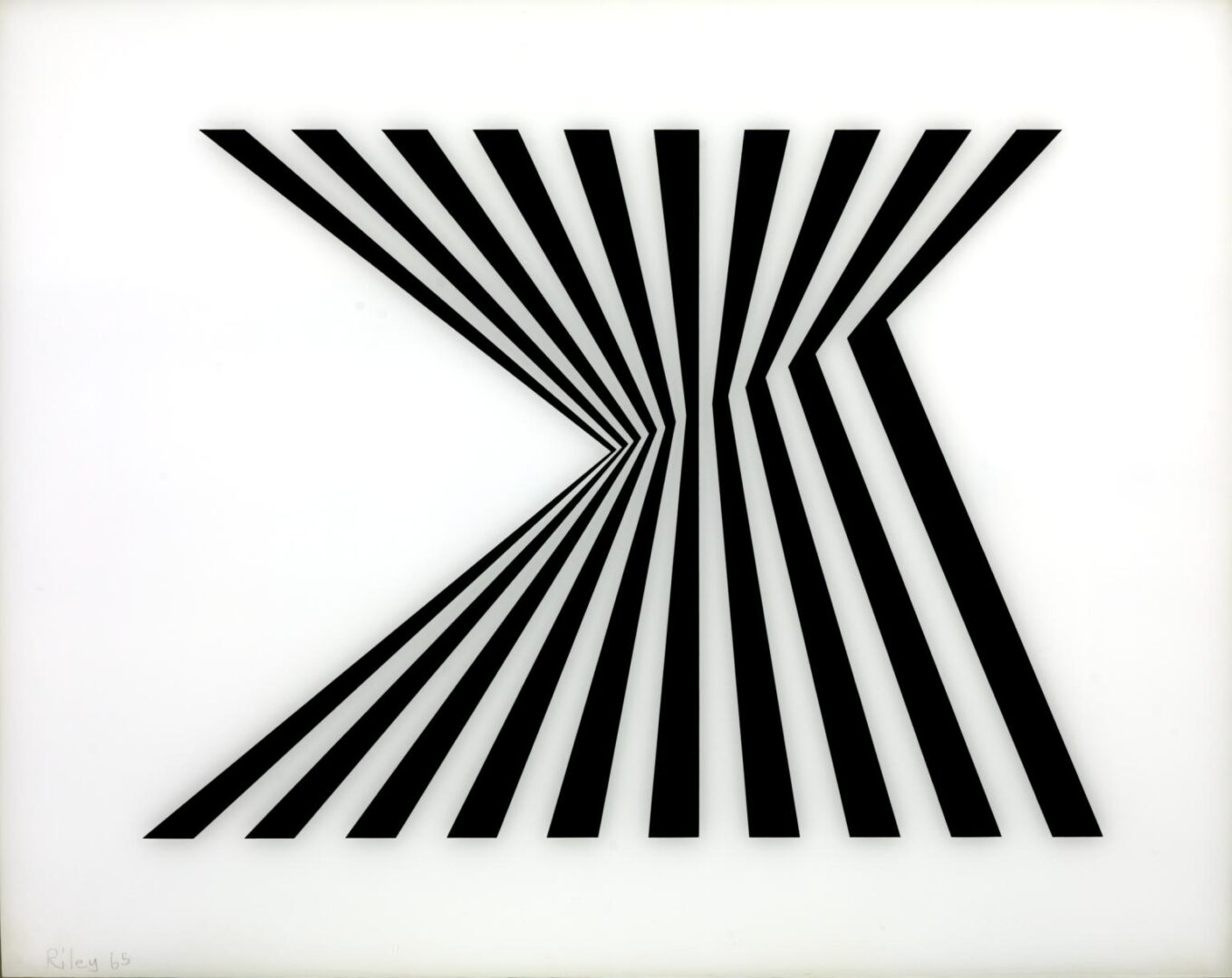

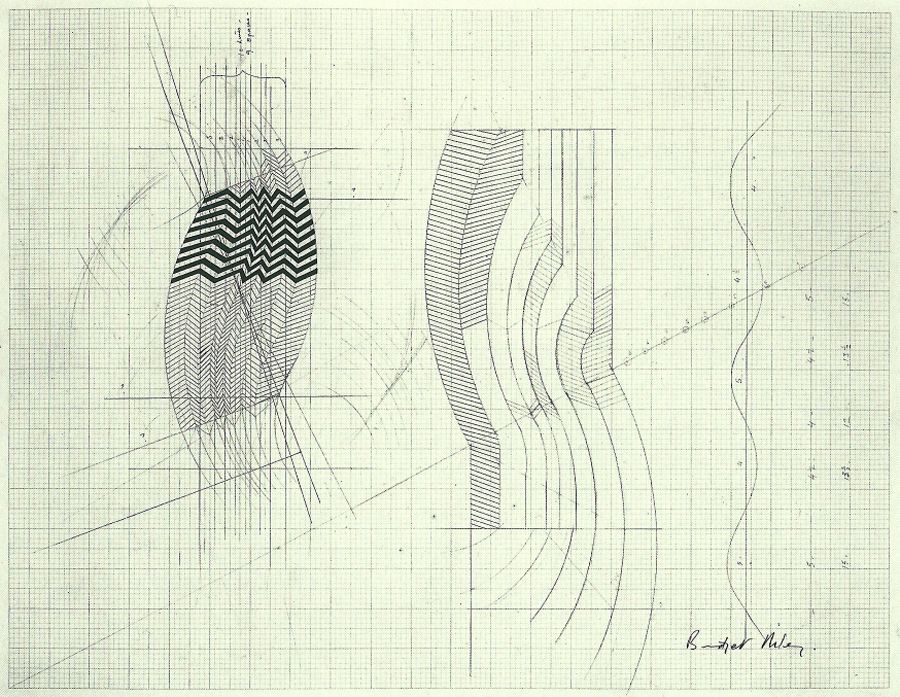

The same analysis can be prescribed to works such as Blaze 1 (1962), Shuttle 2 (1964) and Climax (1963). The apparently homogenous undulations of these works are actually made up of individual zig-zags, the multidirectional chevrons of these lines making the images appear to rotate before our eyes. Close up, Riley’s works are so obviously painted lines on a canvas. Indeed, when we observe the studies for these pieces, done with pencil on grid-paper and built to specific mathematical dimensions, it becomes clear they are architectural in their unshakeable structural logic. Yet, step back a few paces and the information of the painting seems to undermine itself, destroying the marks the artist has made. Furthermore, stare at these ‘black and white’ works for long enough and spectrums of colour emerge on the surface, the works completely defying what we understand as monochrome painting.

A key component of Riley’s practice is a rejection of objecthood and subjectivity. The artist even removes her physical presence from the works, using assistants to paint her finished pieces. Her works therefore have an appearance of anonymity to them, individual without being personal. The paintings are autonomous in themselves; with no hint of an artist’s intervention visible, the movement of these inanimate objects seems to emerge out of nowhere,unable to be controlled. Again, my frustration was built up in this respect when contrasting Riley’s works to her pencil sketches, which clearly reveal how each oscillation was decided upon by Riley personally. Interpreting the finished works as so mechanical, seemingly born out of nowhere, yet also becoming so aware of how they were in fact conceived by specific human hands, makes this viewing experience even more disorientating.

My discussion of this sensory frustration should in no way be read as a criticism of Riley’s practice. The inability I feel to comprehend a Riley is exasperating, but completely brilliant. It is Riley’s paintings, not the viewer, that hold the power; they are intimidating, yet utterly ingenious – a static object has the power to incite nausea, to incite frustration, to entirely confound the senses.

Featured image: Bridget Riley, Untitled [Fragment 1/7], 1965. Screen print on perspex. 65.7 x 82.8 cm. Tate Collection. Image source: Tate.