THOMAS NGUYEN interviews Sharon Yip and Magda Tchorek-Bentall, the director and curator of UCL Anatomy Society’s first-ever art exhibition, Disjointed Anatomies.

On Saturday 2nd March, the UCL Anatomy Society will be holding its first-ever art exhibition around the theme: ‘Disjointed Anatomies’. For an entire day, the South Cloisters will transform into a curated display of intersectional works from student of all academic backgrounds. Each artwork will showcase a unique interpretation of the anatomical body. Sharon (Exhibition Director) and Magda (Curator) share their thoughts:

Talk me through your roles in organising Saturday’s exhibition.

Sharon: We started this project last year when I was elected exhibition director at the AGM of the Anatomy Society. This role did not exist before so I’ve had the freedom to make it – just like the exhibition – largely what I wanted it to be. I started thinking about it in June last year and the concept has been up for discussion for a few months within our team which is made up of five students.

Magda: I’ve been arranging the artworks in relation to the space and to each other. I was also helping out with constructing some of the pieces themselves – and will hopefully be able to showcase my own if I finish it on time. The process of working out how to display things artistically has for long been a fascination.

What was the creative process like? What’s the idea behind the exhibit?

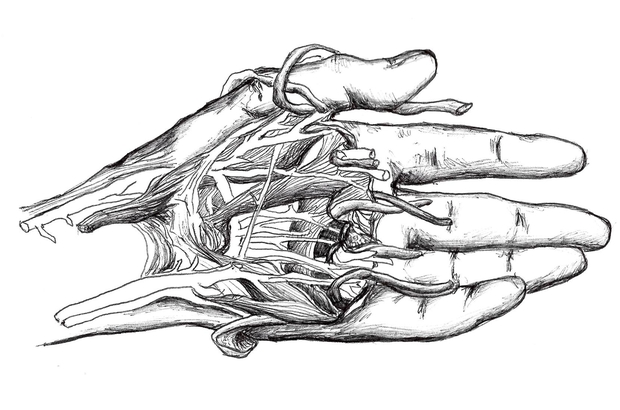

S: I wanted this exhibition to be about the unexpected beauty of scientific images. As medical students, we often ignore the intricacies of what we’re viewing – whether that be histology slides or dissections of the human body. I think it is important, even for medics and scientists, to have that visual literacy. It helps to better understand how parts relate to each other and that’s what anatomy is all about: understanding how bodily structures relate to one another. There’s an almost-anthropological side to it. We’re comparing how people view anatomy, not solely from a purely medical or artistic perspective but also from students who are already binding scientific knowledge and art in their degree.

How many submissions do you have?

S: We have a total of 36 artists and 45 artworks. 50% of our population are medical students and most of the rest was comprised of master students reading all sorts of sciences. We, of course, have also had submissions from art students – mostly from other universities. This is an intercollegiate event!

Why do you think it important to draw that link between anatomy and the arts?

M: What I found most interesting was the comparison between different ways of expressing the body among that intersection of people from science and the arts. The aim here is not to define ‘good’ or ‘bad’ art, or even what the works visually look like. It’s about acknowledging that medics, scientists and humanists all have their personal understanding of anatomy. We don’t get the opportunity to do that a lot in medicine, for instance, while many of us have strong individual experiences dealing with anatomy (surgery to name the most obvious instance).

S: Many of the medical students who submitted have used anatomy to individualise their personal feelings and experiences in the outside world. It’s about that sense of disjointedness that can be expressed using anatomy, which I find really fascinating as a tool for intersectional education. On the day we’ll have an interactive table where we’ll lay out drawing materials alongside anatomical models like skulls and pelvises. People will be able to play with them and have a little draw if they want.

A cheeky one that just popped to mind – what part of the body do you think is most visually pleasing?

S: For me, it’s got to be the place between the sternum and the clavicle. I find this sort of T-shape area most interesting because it’s the best indicator of your body position. If you’re crouched down, for instance, your collarbone will be most pronounced as a continuation of the shoulder joints. Oh man how much I loved writing essays about the hip joints, the shoulder or the clavicle as an undergrad!

Thank you for this distinctly medic response.

M: I’ll give you a wavy answer. I think it really depends on the situation where you present the body. I’ve had incredibly strong visual experiences in the last few weeks in the operating theatre at the hospital. It would be incredible to photograph some of the things I’ve seen like watching someone having his face opened up.

S: PG 13!

M: There was a contrast between the cold, blue surroundings of various pieces of equipment and the professionals’ uniforms, and the inside of the face which is red and yellow and warm. The fat, skin muscles and bones were brightly lit and fleshed out under the spotlight. It was truly stunning.

S: That’s actually why it’s called an operating ‘theatre’. The firsts anatomical theatres appeared in the 15th century and were built in a conical structure to allow people to witness the dissections across several floors. I found it interesting how the inside body has historically been a very public fascination. This directly parallels with the idea behind our exhibition.

What would you like people to take away from ‘Disjointed’?

M: It would be amazing if this would inspire more people in science and humanities to attempt individual explorations of their academic material.

S: I hope this will inspire students to undertake their study of anatomy in a more considered and emotional manner, using this as a platform to think about how bodies can contribute to how we view the world. I’d also like this exhibition to live on so we can more frequently cross that bridge between medical and art students. We have so much in common. For example, where you hold the scalpel in surgery is the same place as where you would hold a pen or a brush. Medical abilities can be highly transferable to art, and I wish artists could share their skills more often with us too.

Featured image: Artwork by Sharon Yip. Image courtesy UCL Anatomy Society.

‘Disjointed Anatomies’ is running from noon to 9pm this Saturday, 2nd March. Tickets are £1.50 and include free drinks and snacks. Find the event here for more details.