ISSARIYA MORGAN traces the imprint of Ovid on Western literature and thought even up to the modern day.

The end of March offers many delights; St Patrick’s Day; the Spring Equinox; Hanami cherry blossom viewing if you are lucky enough to find yourself in Yoshino, Japan. It also marks the birthday of Publius Ovidius Naso. Known more often simply as Ovid, this Roman poet boasts a gargantuan legacy that has left an indelible mark on the Western literary cannon. From Shakespeare to Bob Dylan, literary giants across the ages have constructed their masterpieces upon the foundations of Ovidian lore. Today, he is best known for his epic work, Metamorphoses, a dizzying compilation of myths which covers everything from the creation of humans to the deification of Julius Caesar, and forms the bedrock of Western story-telling tradition.

One of the most noteworthy literary figures to borrow freely from Ovid was the fourteenth century poet Petrarch. Credited with profoundly influencing writing in Renaissance Europe, particularly through his pioneering of the wildly popular sonnet form, the Florentine poet’s debt to Metamorphoses is evident in his magnum opus, Il Canzoniere. Petrarch’s work centres on his love for a woman named Laura, a pun on lauro (‘laurel’ – the symbol of poetic fame), which in turn is a translation of the Greek daphne. In the collection’s twenty-third poem, ‘Nel dolce tempo de la prima etade’, the narrator imagines himself transformed into the symbolic laurel tree:

What a state I was in when I first realized

the transfiguration of my person,

and saw my hair formed of those leaves

that I had hoped might yet crown me,

This metamorphosis and its symbolism derive from the tale of Daphne and Apollo, undertones of which permeate Il Canzoniere. The god of poetry, infatuated with Daphne the river nymph, pursues her through the woods until she transforms into a laurel tree to evade his clutches. It is by now an iconic scene which has been retold on countless occasions. Shakespeare pays homage to the tale in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where Helena assumes the role of Apollo as she chases Demetrius through the woods, crying out:

The wildest hath not such a heart as you.

Run when you will, the story shall be changed.

Apollo flies and Daphne holds the chase.

Teeming with magical transformations, interactions between gods and humans, and messy romantic entanglements, Shakespeare’s comedy draws heavily on the bawdy, unpredictable Ovidian world. The Bard revisits the tale of Pyramus and Thisbe, which provided inspiration for Romeo and Juliet, and gives the story a comic twist in Midsummer by presenting it through the medium of the mechanicals’ questionable acting.

Shakespeare is only one of many to give Ovidian narratives an unconventional twist. Current poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy reframes the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice from a woman’s perspective in her poem, ‘Eurydice’. In its Ovidian form, Eurydice is a passive female muse who is pined after and longed for, perhaps symbolic of the poet’s quest for the perfect form. She is voiceless, serving as the sounding board against which the male voice can exhibit its own poetic prowess. Orpheus is the archetypal bard, representative of the dominant male voice throughout literary history, who spins stories as he pleases, negating the female perspective. In her poem, Duffy redresses this imbalance by transferring the poetic authority to Eurydice, enabling her to tell her story on her own terms:

And given my time all over again,

rest assured that I’d rather speak for myself

than be Dearest, Beloved, Dark Lady, White Goddess etc., etc.

In fact girls, I’d rather be dead.

But the Gods are like publishers,

usually male,

and what you doubtless know of my tale

is the deal.

Duffy’s poem gives the age-old tale of Orpheus and Eurydice a poignant feminist reworking, illustrating the capacity of Ovidian narratives to provide frameworks for new stories to be told.

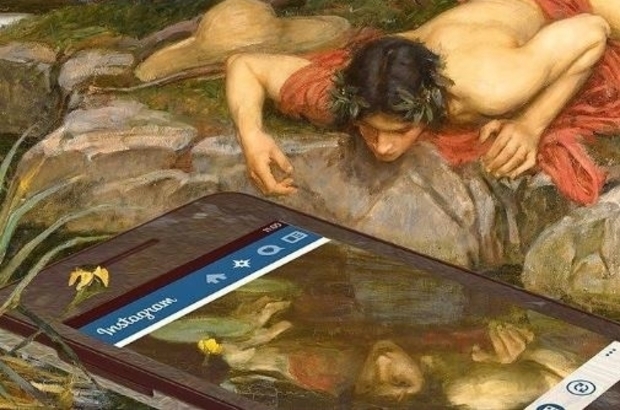

Ovid’s influence extends to the words we use, and the systems through which we understand ourselves. Take, for instance, the tale of Narcissus and Echo. The beautiful Narcissus is adored by the nymph Echo; he spurns her advances out of a disinterest in love, until he unknowingly happens across his own reflection in a pond. Confusing his reflection with the face of a stranger, he is enthralled by the beauty he sees, and is driven to death by its unattainability. As Ted Hughes envisions in Tales from Ovid:

Then he ripped off his shirt,

And beat his bare chest with white fists.

The skin flushed under the blows.

When Narcissus saw this

[…]

It was too much for him.

Like wax near the flame,

[…]

He melted—consumed

By his love.

Through heartbreak, Echo fades away until only her voice remains, fated to repeat the last words of anyone nearby. From this we get the modern definition of the word ‘echo’, as a sound repeated by reflection. The linguistic inheritors of ‘Narcissus’ have contrastingly become entwined in Freudian psychoanalysis. ‘Narcissistic’ is a word now used to describe a person who takes an excessive interest in the self, resulting in problems maintaining healthy relationships with others. Freud modelling his twentieth century theory on Ovid’s ancient tale attests to the power of stories to influence how we understand and articulate our experiences.

Ovid’s immense legacy testifies to the formidable power of story-telling, and the centrality of fiction to the human experience. Tales such as those found in Metamorphoses have no expiry date; they are continually reimagined in an endless echo through time. Perhaps the canny Roman recognised the power of his stories as the gateway to immortality when he ended the Metamorphoses with the words:

Throughout all ages, if poets have vision to prophesy truth,

I shall live in my fame.