LEAH AARON considers the representation of queer women over the past two decades of television and cinema.

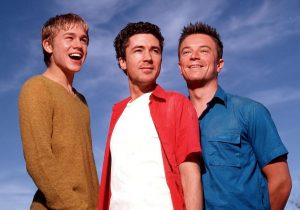

I was fifteen when I first watched Queer as Folk. I would’ve been four when it was first broadcast (in 1999), but I’d read somewhere that it was about gays and Manchester – two things which interested me enormously at the time – so I streamed it on Megavideo. The Channel 4 series was Russell T. Davies at his brightest and best: it centred around Stuart, Vince and Nathan, in a fraught and emotionally manipulative love triangle. The first episode sees Nathan (who is fifteen!) sneak out to town, get picked up (by Stuart) and rimmed in a trendy warehouse loft, all in the first five minutes. Later episodes involve arson, attempted blackmail and an endless stream of casual sex. Everyone was cultured, complex, morally ambivalent and always on the prowl. I was suddenly aware of an exciting, attractive and dangerous hidden world just a bus ride away. This, I assumed, was what it was to be queer.

I was naïve, of course. The intervening years have not only seen LGBT+ culture as it was depicted in Queer as Folk die out (Canal street, where the show was set, has been devitalised over the years by a steady encroachment of hen parties and straight couples looking for ‘an adventure’) but also opened my eyes to just how narrow a depiction of queerness it was. Yes, Vince, Stuart and Nathan were compelling characters, relatable-to in a myriad of different ways, but they were all gay men: well-to-do, white gay men. I’d made the mistake of equating the whole of LGBTQIA+ culture with a very specific gay male one, which I think is totally understandable, because the only other representation of queerness I’d seen were lesbians, and they were fucking boring. Russell T Davies’ lesbians were frumpy, staid and maternal. They existed mainly to provide a juxtaposition to the hard-partying gays, and participate in a semi-comic subplot in which one of them nearly gets seduced by a man (oops!) so he can try and get out of being deported (the nineties!). It was easy to ignore them.

That was 1999, though. Eighteen years ago. Things have moved on, right? We now have reams of airtime, not to mention hours of film, devoted to queer women’s experiences, like, Blue Is the Warmest Colour (2013), and Carol in (2015), and The Handmaiden, which came out this year. I don’t think I read or heard a single bad review of any of those films in any of the major news outlets; Front Row was practically effusive. And they’re all such unique and beautifully crafted films – one of them follows a young, beautiful artist who seduces a younger, beautiful teenager! And in Carol this young, beautiful photographer is seduced by a glamourous older woman! And in the Handmaiden, this young, beautiful maid…

Obviously these films are not bad. They are all visually stunning, creations of lauded directors, and I have paid money to see more than one of them in the cinema. But where Queer as Folk, despite its many faults, didn’t shy away from portraying gay men as messy, flawed, desperate (so, human), all too often this kind of grandiose, sweeping ‘lesbian’ cinema seems to use female same-sex desire as a vehicle, a metaphor for the male directors to make commentaries on Life, Youth and Beauty, that form a pretty but unthreatening attraction for the male gaze. It is telling that in each one of these films, the competing love interest is a heterosexual man, to whom one of the characters is always just a heaving bosom away from being seduced by, whereas in Queer as Folk the characters pretty much never leave the all-male sauna.

Lesbian sexuality is often portrayed as passive, inert, waiting to ‘flower’ at the touch of a conventionally attractive, nominally older woman woman (and always decisively ‘Lesbian’, as though the myriad sexual and gender identities we see in real life cannot physically transfer onto film). It’s then kept tastefully under wraps, communicated only with knowing glances that allow for extended close-ups of the actresses’ beautiful face, until the denouement of a lukewarm, weirdly choreographed sex scene. This portrayal of female sexuality as hesitant, tepid, in need of decisive guidance, not only portrays women as unable to take control of their own desire, but also subtly reinforces the idea that it is somehow in the public domain, an object which others have the right to take possession and control of. In casting these queer love stories in the narrative of seducer and seduced, these films subtly reassure male heterosexual viewers of the centrality of their viewpoint, implying as they do that same-sex female desire is merely a half-hearted echo of the true Great Love between man and woman.

When Queer as Folk first came out, it was ground-breaking in its realistic and unflinching depiction of the gay male experience. It is a shame that eighteen years later, it feels like we’re still waiting for something that gives queer women as messy, flawed and relatable a narrative, (let alone those whose gender does not fit into the two mainstream, binary categories of ‘man’ and ‘woman’). Queer women are still either delectable baubles for the male gaze or frumpy, sensible killjoys if they are lesbians, and promiscuous, unpredictable and erratic if they are bisexual. Otherwise they are sad, lonely freaks (or they simply don’t exist). Such portrayals still all too often see the press falling over itself to commend them as ‘brave,’ or ‘honest’ by their mere presence. Of course, many of these issues are intractably bound up with the portrayal of women more generally on film, of which there is much, much more that could be said. But I think we’re making progress there, and I don’t think it’s unreasonable to ask for a little bit more. Imagine if two women fell in love and neither of them could remember who made the first move and didn’t have to come out to anyone and weren’t temporarily rejected by their family or society, killed off or seduced by a man? It’s a long shot, but I think we’ll get there eventually.

Featured image courtesy of www.moviepilot.de