INNOKA BARTLETT interviews artist Aysha Almoayyed regarding her exhibition piece at the ArtBAB Pavilion.

Aysha Almoayyed’s Lost Paradise was showcased at the 2019 Art Bahrain Across Borders (BAB) Pavilion as part of Bahrain’s International Art Fair that took place in March – Manama, Bahrain. Displayed in the pavilion were selected works by thirty of the most creative Bahraini artists.

Born in 1988 in Manama, Bahrain, Aysha Almoayyed studied Marketing at Bentley University. She then completed her MFA in Fine Art at Goldsmiths University. Experimenting with mediums including drawing, photography, and installation her artworks explore societal forces in Bahrain and the transformation of the artificial and natural environment. Almoayyed is the youngest recipient of the most renowned art award in Bahrain, the Al Dana Prize.

She shares her opinions on contemporary art in Bahraini culture:

–Your work is featured in the ArtBAB Pavilion – what is your interpretation of this idea of ‘Bahrain Across Borders’, and how do you feel this speaks to the identity and message that you situate behind your work?

‘Bahrain Across Borders’ feels to me like an attempt at a new narrative about the land, people, and stories that occupy the island. I hesitate to say my work has an identity and I definitely don’t intend for it to have a message. Much like the exhibition, I hope that it, in some way, is a creation that reflects the time in which it occupied the island.

-In what ways do you feel as though your artwork internationalises Bahraini culture and identity?

By internationalises do you mean exports Bahraini culture and identity or makes it more relatable to international eyes? I guess something becomes internationalised when it is brought to the international arena, in a way. That being said, I hope the international exhibitions that I have participated in in the past do give the (non-Bahraini) viewer a more independent and individual view. But, I do have to note that I have learned to make art in the UK (at Goldsmiths University) so it could be argued that my language of art is already internationalised and more palatable for a UK audience.

-What messages do you intend to voice through the experimental nature of your artwork?

I don’t really make artwork to voice a message. It’s more for the experience, for me while creating, and for the audience while experiencing it. Take from it what you wish.

-Is there a larger vision that you’re working towards or that you would like to see in the future concerning the artistic representation of Bahrain?

I hope that the future of artistic representation in the region as a whole becomes more intimate and vulnerable. I would personally find that more interesting if it went in that direction. I have seen many people try and tackle very large subjects like ‘identity’ with little impact. I think relaying things that are smaller and more intimate might make a more impactful piece of art. Also, I would like to see artists work with more present mediums like performative arts and more contemporary subject topics that don’t necessarily have to do with heritage or tradition. Those subject topics can be a little overused.

-Could you give us some insight into your installation piece Lost Paradise? What influenced you when producing this?

Most of the content I collect for my work is through WhatsApp groups. WhatsApp groups serve a very important role in the transfer of information in the Middle East. And in my opinion, some of the more influential content that shapes our society travel through these channels.

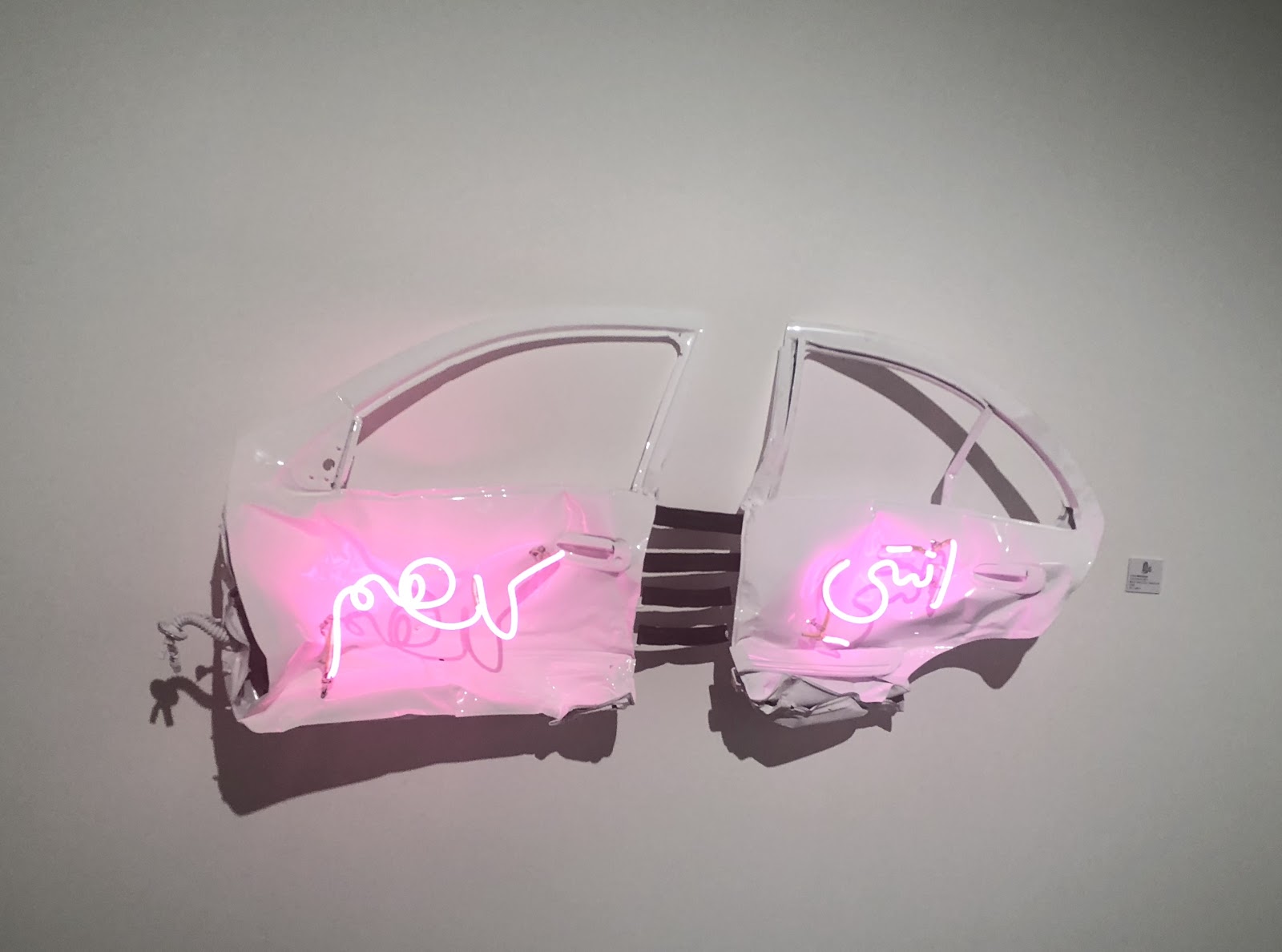

I came across a video earlier this year of two women getting harassed and groped by several men in a waterpark in Bahrain. The waterpark is called ‘Lost Paradise of Dilmun’ which I found to be very fitting for a title since it is so far from that. I wanted to create a work that embodied the feelings of watching the video as a female, and the discussions that took place in our society during the week this video was circulating. The piece touches upon feelings of shame, fear, regret, and blame – mostly feelings taught and experienced by the majority of women and young girls all around the world.

-Is this made specifically for an Arabic-speaking audience? How do you think the visual impacts a non-Arabic speaker when engaging with this piece?

Yes, it is made for an Arabic speaking audience. I think the visual impact to non-Arabic speakers might be a little shocking because the piece is made from the remains of a car crash, but it also has a soft pink neon light element to it so I’m not certain how they would engage with it. I guess it depends on their own past experiences with those elements.

-Having received the Al Dana Prize, can you comment on the value of art in Bahrain and how you think culture and heritage have informed this and might continue to?

Within the last 5 years, I have seen an increasing amount of people either take up practice or have begun participating in the art market in one way or another. This is very encouraging and I am a believer that the more involvement we have in the art world the better our output will be. I do hope to see more participants in the non-commercial side of art. This is what we are lacking here in Bahrain.

Feature Image: Installation view of ArtBAB 2019. Image courtesy of Isobel Jaffray.