MARCELA KONANOVA reviews Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde at the Barbican Art Gallery.

Laced with elements of originality, Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde offers a unique insight into intimacy in relationships. Paramount figures in European Modern Art explores the bonds that negotiate their creative processes. As opposed to many current exhibitions devoted to the development of a work of a single artist, Modern Couples understands art production as an organic process fuelled by the human connection. The rise of Modernist art styles from the late-19th to mid-20th century is seen as the product of the inevitable collaboration and influence rather than the product of a solo genius. ‘Couple’ is an elastic term encompassing all manner of intimate relationship that the artists themselves grappled with. It was not defined exclusively as monogamous, but inclusive of polyamory, friendship, or any relationship defined by devotion.

Each couple brings to light a unique story of collaboration and influence. A little handbook, which is handed to you at the entrance of the exhibition, makes it easy to follow the conceptual threads of each artist couple. The handbook thematises the exhibition in singular words or phrases. It serves as an overarching reference to the overlapping and often simultaneous preoccupations which contributed to their art. Included are motifs such as Agency, Desire, Liberation, Non-binary, Homoeroticism, Muse, Pygmalion, and many more. The most recurrent concepts emerging from the stories of modern couples are, in my opinion, Muse, Experiment and Movement.

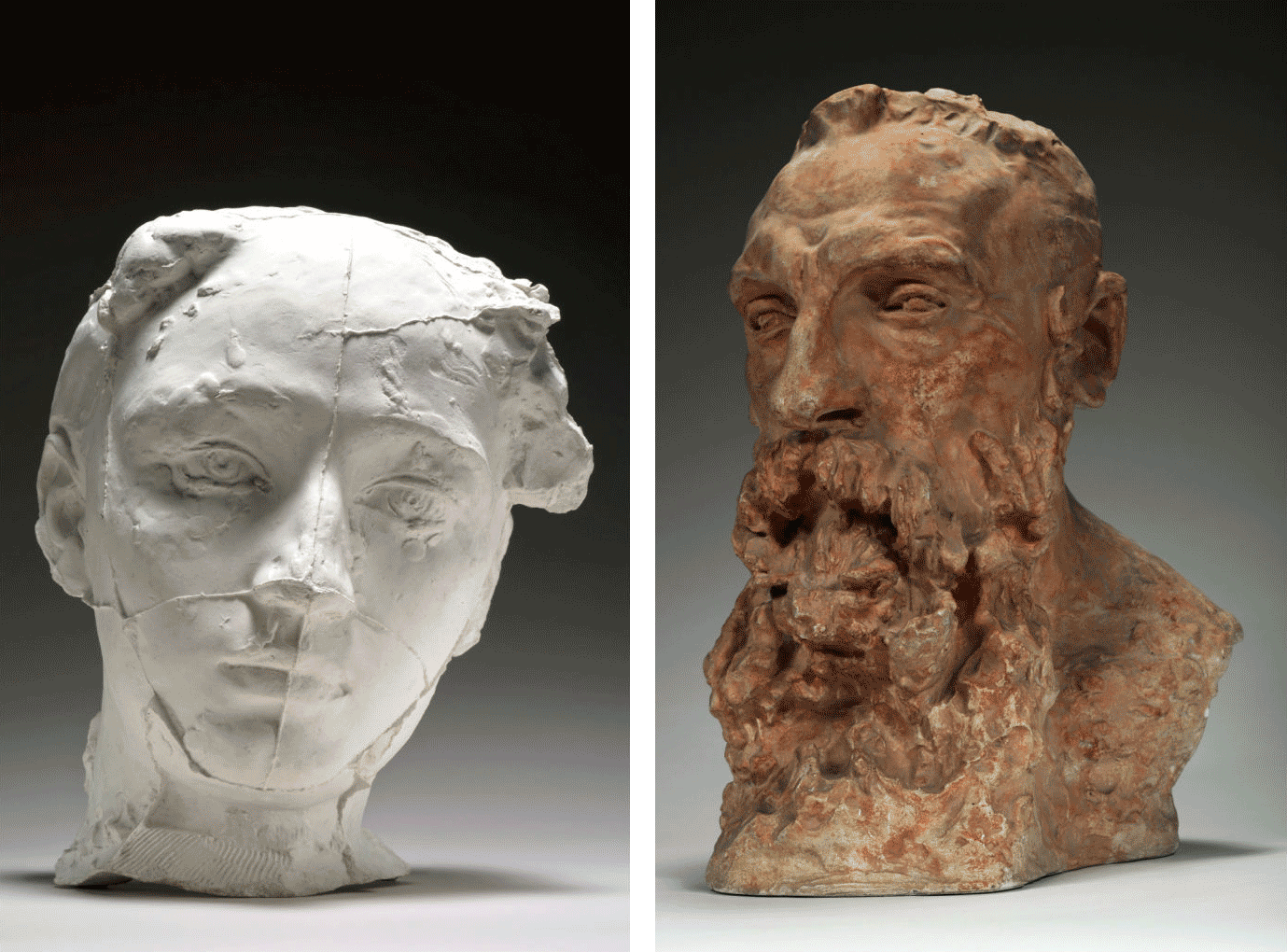

These are concepts which were universally visited by all couples within this exhibition, each in different capacities. Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel’s works introduce the exhibition with musings on their own facial features. The couple carved two busts in terracotta of each other’s faces. Here, the viewer is able to trace the movements of their fingers tenderly fashioning the browline, the cheekbone, an imperfection on the nose. These subtleties, as seen in the style of artistic production, begins to exemplify Muse, Experiment, and Movement which frame the exhibition’s investigations into intimacy.

The artwork that first captured my attention was this sculpture of Rodin. Upon examination, I thought immediately: ‘What is he looking at?’ I followed his gaze and came face-to-face with the bust of Camille: a white, similarly well-mastered head, fashioned tenderly by Rodin. Their creations are musings upon the other’s physiques. I imagined the two of them intricately exploring facial features of the other, and gently shaping the terracotta clay into the studies Étude pour Sakountala and Le Basier, (equisse). The soft gaze of the busts are touching in their gentleness and modesty. The viewer intercepts this moment of privacy, contemplating this revelation of a quiet moment of moving affection between two people.

A similar occurrence is shown in the relationship between Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar. Maar, as a photographer, took photographs of Picasso and edited them with her surrealist touch. Conversely, Picasso used Maar´s image as a model for his portraits, an act which she did not always approve of. Frida Kahlo’s painting, The Wounded Deer, on the far side of the wall changed in meaning throughout the process of my viewing. The quote on display alongside the painting reframes the image depicted: ‘DIEGO in my urine, DIEGO in my mouth – in my heart in my madness, in my sleep.’ This quote reveals the deep devotion Kahlo felt for Diego Rivera despite having often felt driven into ‘madness’. Diego present in her sleep, her urine, her mouth references a state of toxicity within their relationship which was damaging to all aspects of her bodily experience. Essentially, Kahlo references the emotional trauma of such a volatile romance in portraying herself bloodied and wounded.

This exchange of pain and passion seemed usual among the many artist-lovers. Though the word ‘muse’ is in our society most often personified as feminine, there are various instances of men as muses for their lovers’ art in the exhibition. This is revealed in the representation of non-binary relationships which break down heteronormative tropes of representation. These caricatures are the singular definitions of the muse as a feminine entity which continues to define visual conventions within Western art production. The relationship between Federico García Lorca, a radical Spanish playwright, poet, and theatre director, and Salvador Dalí produced passionate words and illustrations which came to embody their volatile adoration for one another. Dalí wrote to Lorca, in the summer of 1928: ‘You are a Christian whirlwind, and you are in need of some of my paganism.’

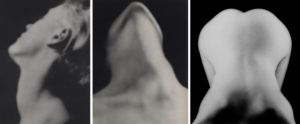

It is not only the lover but also the union of the two lovers that can inspire an artwork. When two creative minds join their experience and vision, a new experimental art form is likely to develop. In the 1930s, that is precisely what emerged from the relationship between Nancy Cunard, a poet and a journalist, and Henry Crowder, an Afro-American jazz pianist. From the collaboration between Cunard and Crowder, a publication called ‘Henry-Music’ was born. The magazine contained poems by Cunard and other poets along with music written by Crowder, so the publication offered early conjunction between poetry and jazz. Another interesting experiment came about in photography from the collaborative works of Lee Miller and Man Ray. Their love affair inspired their experiments with highly eroticized surrealist photography. In the photographs below labelled Neck and Nude bent forward, one can observe the unconventional posture of a captured female body in an unusual lightning characteristic for Ray’s and Miller’s technique.

Love affairs and relationships are also fruitful for the development of ideological and artistic movements. ‘Room 3’ of the exhibition is fully devoted to how feminism and liberal gender ideology progressed through efforts by creative couples. One of these influential relationships is between Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. Even though their romance lasted for only three years, they remained close in their later years. Through creative collaboration, Woolf’s literary works of androgyny flourished. Their platonic closeness is emblematic of the desire for independence and agency which underpinned much of the work by women artists in the avant-garde period. Discussing agency, Woolf states ‘I want to forge ahead, on my own lines.’ Woolf reclaims a form of emotional independence from Sackville-West through the termination of romance. The exhibition instead celebrates the value of platonic intimacy, while also acknowledging the significance of their romance.

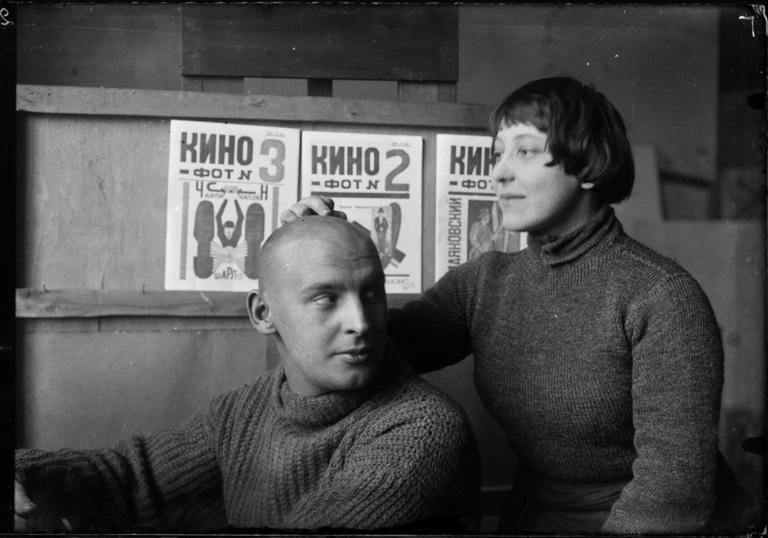

Another couple who used their art to convey political ideas was Varvara Stepanova and Alexander Rodchenko. The two lovers made art displaying their support for Communist Russia in the early 20th century. The pro-communism movement the two artists were a part of was called Constructivism and its aim was to provide a platform on which society could express themselves through creative means. Promoting the idea of equality, the movement declared design and photography as equals in value with other forms of fine art. Exclaiming: ´We are the proletarians of the brush! Creator-martyrs! Oppressed artists!’ Rodchenko expresses the couple’s dedication to the revolution.

From painting, sculpture, photography to music, literature, design or costume making, a diverse range of artistic channels are represented. Likewise, artists of various nationalities made their way into the exhibition. European artists ranging from Britain to Russia, American as well as Mexican artists are included. However, it must be noted that the coverage of Asian, African or Australian is weak. Modernity and the avant-garde produced a wealth of artists operating outside the Eurocentric scope of art who were disappointingly excluded from the exhibition’s curation. As a result, the primary focus of this review has been an exploration of the multifaceted sides of intimacy as seen in Western Modernity.

Whether it be a liaison, a life-long relationship, a same-sex relationship, a love triangle or a traditional marriage between artists, Modern Couples points out the salient factor of human connection as a great source of artistic creativity. The exhibition gives credit to the accomplished yet largely disregarded and forgotten women-artists who made art alongside their more-famous male-partners among the European Avant-Garde. Overall, Modern Couples highlights the collaborative nature of making – it puts on display the intimacies that led to the creation of some of the most influential artworks produced in the West to date. The exhibition is encapsulated in André Breton’s reclamation of love as a unified, multifaceted emotion: ‘Only love remains beyond the realm of that which our imagination can grasp.’

Featured image: Tamara de Lempicka, Les Deux Amies, c. 1923, oil on canvas. Image credit: Association des Amis du Petit Palais, Genève. © DACS 2018.

Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde is on exhibition now until the 27th of January, 2019 at the Barbican Art Gallery.