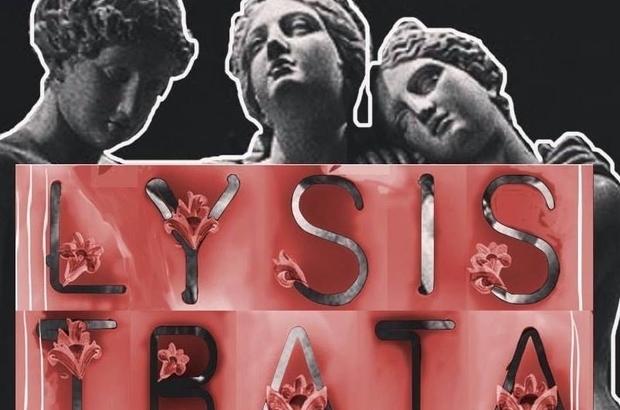

ELLA WILSON and SELMA REZGUI review Lysistrata.

Euripedes was right. There is no beast so shameless as woman.

Aristophanes’ Lysistrata is his most frequently performed comedy, and for good reason. Sex and war are timeless and fundamental to the human experience, and, as is so often the case, the female body becomes a battleground onto which political and social tensions are transposed. The themes of sex as power and the vying for agency between the genders is prescient today, at a time when conversations about consent, bodily autonomy, and sexual abuse are dominating the media. Exploring proto-feminist themes through the lens of our time, the UCL Classical Play is a modernised version of this lewd ancient Greek comedy, which deviates while remaining true to Aristophanes’ spirit – because, after all, jokes about the size of codpieces will never not be funny.

Fleur Elkerton’s brilliant and unconventional production design is described as ‘Renaissance meets club-kid aesthetic’. The set deploys sparse shapes to suggest the architecture of renaissance Europe, while accents of neon modernise it, and its largely neutral palette makes the costumes our focus. Elkerton and director Richard Sansom situate Aristophanes’ play in a flamboyant and strange version of civil war England, in which couture corsets and elaborate codpieces coexist with bondagewear and sculptural plaster bodices. These bold, beautiful stylistic choices enhance the air of absolute absurdity, and costume is used to play with both time and gender.

The chorus accent the main action of the play with their presence, separated by gender (of characters, not of cast) and the sizeable expanse of stage between men and women. Their costumes move between passionate reds and sensual nudes, providing a canvas for plentiful bawdy visual gags. This is a play in which gender is everything – and biology becomes a bargaining tool. The fact that this production has been cast with joyous disregard for gender works well here. Everyone performs a heightened version of their gender which adds to the atmosphere of sexual hysteria on stage. From Philipp Koehler’s screeching crone to Patrick McPherson’s hypermasculine Cinesias, trying to persuade his wife (played with beguiling coquettishness by Zac Peel) to submit to breaking her vow and sleep with him, incapacitated by his enormous and evidently excruciating erection, the ensemble cast create a hilariously unlikely cabaret.

The play successfully establishes, and then goes on to demolish in almost every conceivable way, a binary of gender, power, and agency. Men and women are reduced to their sexual organs, grotesquely approximated by the aforementioned props, which are assigned to the cast arbitrarily. The women of Lysistrata are overflowing with sexual desire and agency; much of the play’s comedy arises from the fact that it is as much a painful trial for them to withhold sex as it is for the men to have it withheld from them. As the women embark upon their own battle, discovering how to utilise their limited domestic sphere, their makeup looks like war-paint, or the dark eyes of Mad Max’s Furiosa, and the modern accents of their costumes like armour. Lysistrata herself (Hannah Parker) is presented as an assertive and resilient warrior, an unwavering woman who can hold her own in an argument, even when faced with the most mindless of misogynists.

The play’s final tableau, in which Lysistrata stands tall, her dress and plaster bodice proudly proclaiming her a woman, her armour proudly proclaiming her a warrior, equates her with the Greek goddess Athena, of wisdom and war, as well as Queen Elizabeth I. Her climactic speech, in which she asserts ‘I am a woman, but I am not a fool’, re-contextualised in the production’s renaissance setting takes on connotations of Elizabeth I’s Spanish Armada speech: ‘I may have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and soul of a man.’ As Alan H. Sommerstein writes of Lysistrata: ‘If she is a peacemaker, she is a tough one.’ The women of Lysistrata are neither weak, nor feeble; they are flawed, sometimes reluctant, peacemakers, and set against the weak-willed military men, who descend to increasingly, comically pathetic depths, the women become warriors.

Richard Sansom’s direction successfully draws universal comedy out of Aristophanes’ text, while also staging unscripted sequences which utilise the equally universal phallicism of aubergines and baguettes. Although at times, the first act feels slow and lower-energy, the second sees the actors return with renewed vigour, heightened bawdiness and well-timed punchlines. The production team and cast have crafted a timely, experimental and above all, hilarious, piece of theatre, which, once past the largely expositional first act, finds its way as a highly inventive ensemble piece, merging the disparate worlds of the play’s ancient Greek origins and Renaissance England with irreverent flair.

Lysistrata played at the Shaw Theatre from 7th-9th Feb. Find more information here.

Featured image designed by Fleur Elkerton.