RUBY ANDERSON reviews UCL Art Society’s Virtual Exhibition, Natural/Unnatural.

The theme of UCL Art Society’s annual exhibition could not have been more prudent for the current global climate. Natural/Unnatural emphasised the disparity between the things we accept or assume to be normal and that which is fact extraordinary, uncanny, or even disturbing. Questioning what is perceived as ‘natural’ at a time where normal life has been put on pause is refreshing in its ambiguity; as the opening line of the exhibition’s foreword purports, this theme raises more questions than it answers. This of course led to an enormously successful degree of creative interpretation.

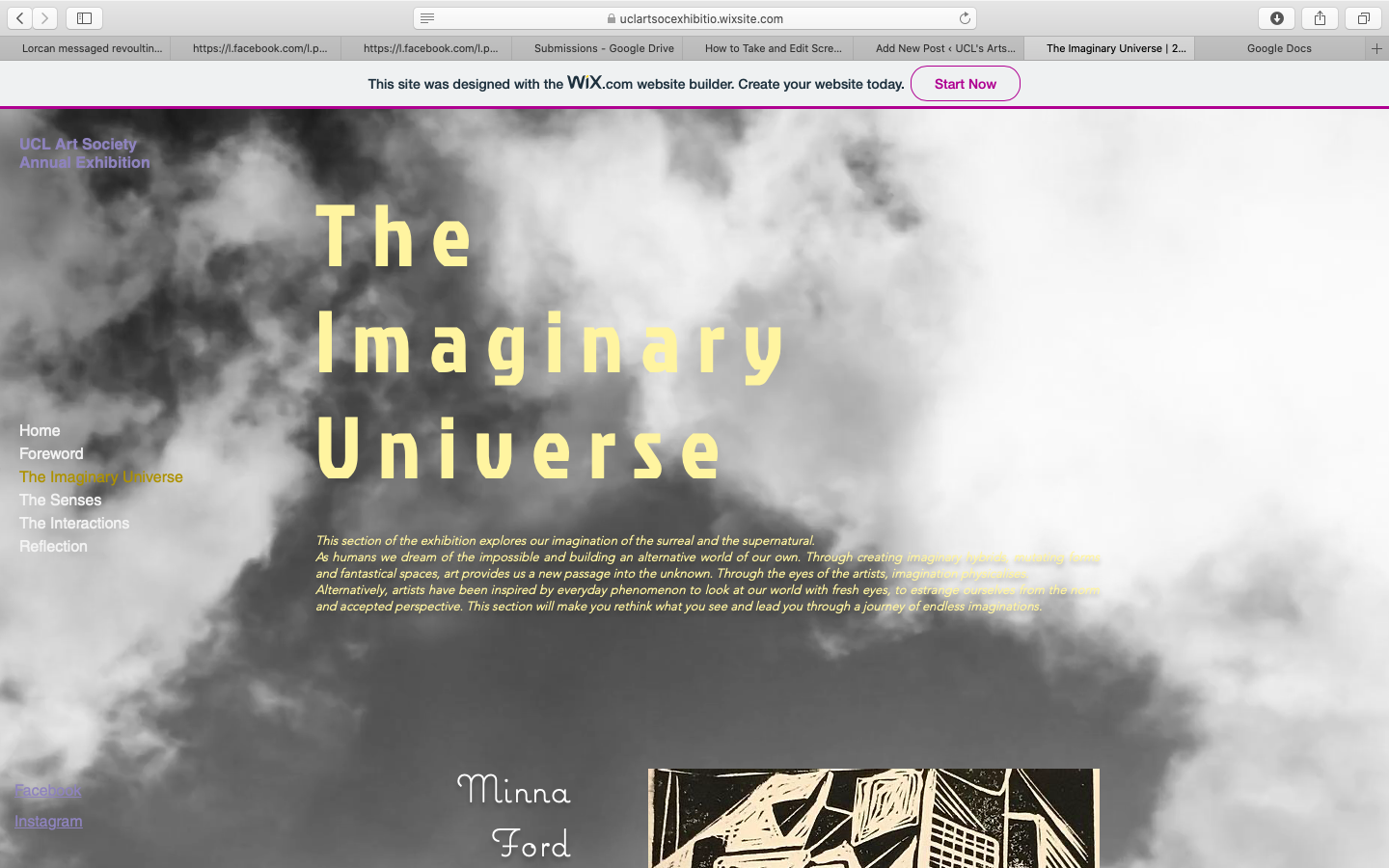

Firstly, the cohesiveness of this exhibition must be praised considering its digital format. Like many galleries this year, UCL Art Society were forced to make their annual exhibition available for online viewing. In my previous experiences, viewing artworks online can often make works feel flat or muted, their power diminished to the dimensions of a laptop screen which acts as both a physical and metaphorical barrier between the work and the viewer. However, this exhibition seems to consciously compensate for this, with the website’s features meaning site visitors have to click on different tools to reveal information about the works and their creators, engaging with the resources being provided to them.

The first section of the exhibition is titled The Imaginary Universe and explores the overall theme from the perspective of the surreal. ‘Through the eyes of artists,’ the accompanying text reads, ‘imagination physicalises’. The immersive nature of the site works especially well in this section: a constant moving visual of black and white rolling clouds provides a backdrop for the artworks, which often made text difficult to decipher. As a viewer, I felt this drew me in further, forcing me to concentrate on each word. Reading something off of my laptop screen, an activity I do every day, was now being made complicated and disorientating.

Each of the exhibition sections is complete with a soundscape by Lucia Affaticati, which can be treated as individual works in themselves or, as I opted to use them, as accompanying auditory stimuli that set the tone for the viewing of each section’s content. In Asbestos for example, the synth sounds are quite unsettling, which made me feel alert in my process of viewing – it made me aware that what I was viewing was an exploration of things unknown.

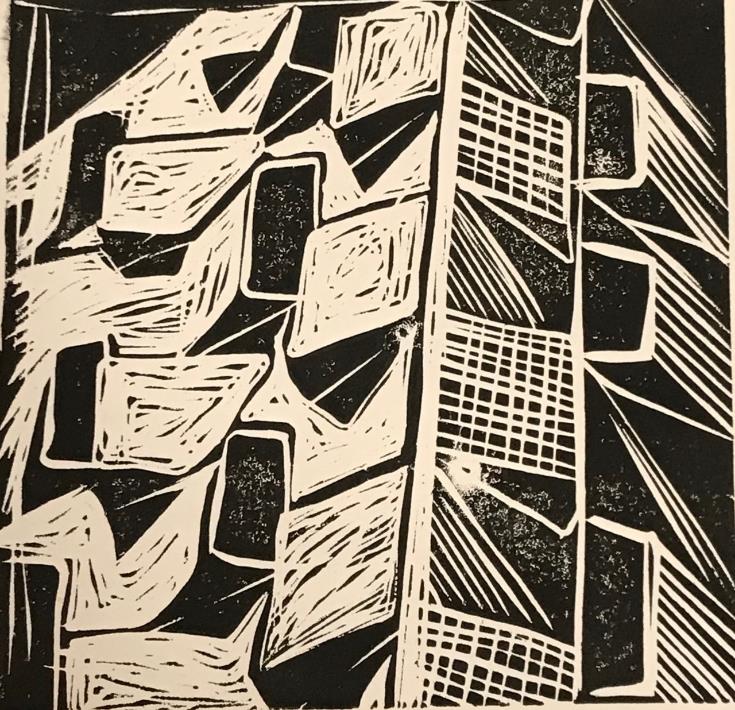

Even within this subtheme of the exhibition the works are expansive in the ideas that they put forward. Minna Ford’s lino print, Burning of Ghent, explores rigidity in architecture, repeating typical elements of a building’s façade until they appear to be more textural than structural. Gabriel Moshenka’s Friends, face to face, a wood carving, was a particular favourite of mine. He created the work by carving a walking stick used for hiking in the mountains into figurines, whose forms were dictated by the natural bends and grains of the wood. The artist delineates that when he cut himself carving, he put a little blood in their mouths, and that when he plays cards, he rubs the figurine’s bellies for good luck. The bizarre personal nature of this object fascinated me, with the piece being framed in an artistic context but simultaneously being used by a contemporary individual for non-artistic purposes. Sabrina Gao’s Nightlife also stood out to me. The work explores the traumatic nature of sleep, this being something that we accept as simply a part of human existence: ‘How do we go about our daily lives, having lived through a multitude of traumatic experiences in our sleep?’ the artist questions. The engorged acid-yellow eyeball depicted by the artist communicates this paralysis.

This section also highlighted many impressive examples of photography. Shreya Katwa’s Perspective was taken as she flew over Mauritius. It highlights the irony of viewing natural beauty through manmade objects, such as through aeroplane windows or mobile phone cameras, redirecting the theme towards the phenomena of ‘natural’ versus ‘manmade’. Johara Meyer’s Plop explores the impermanence of people in specific locations. The photo depicts an individual suspended in mid-air, completing a dive, their body not yet fully extended. This suspenseful moment is seconds away from being nothing but a passing memory.

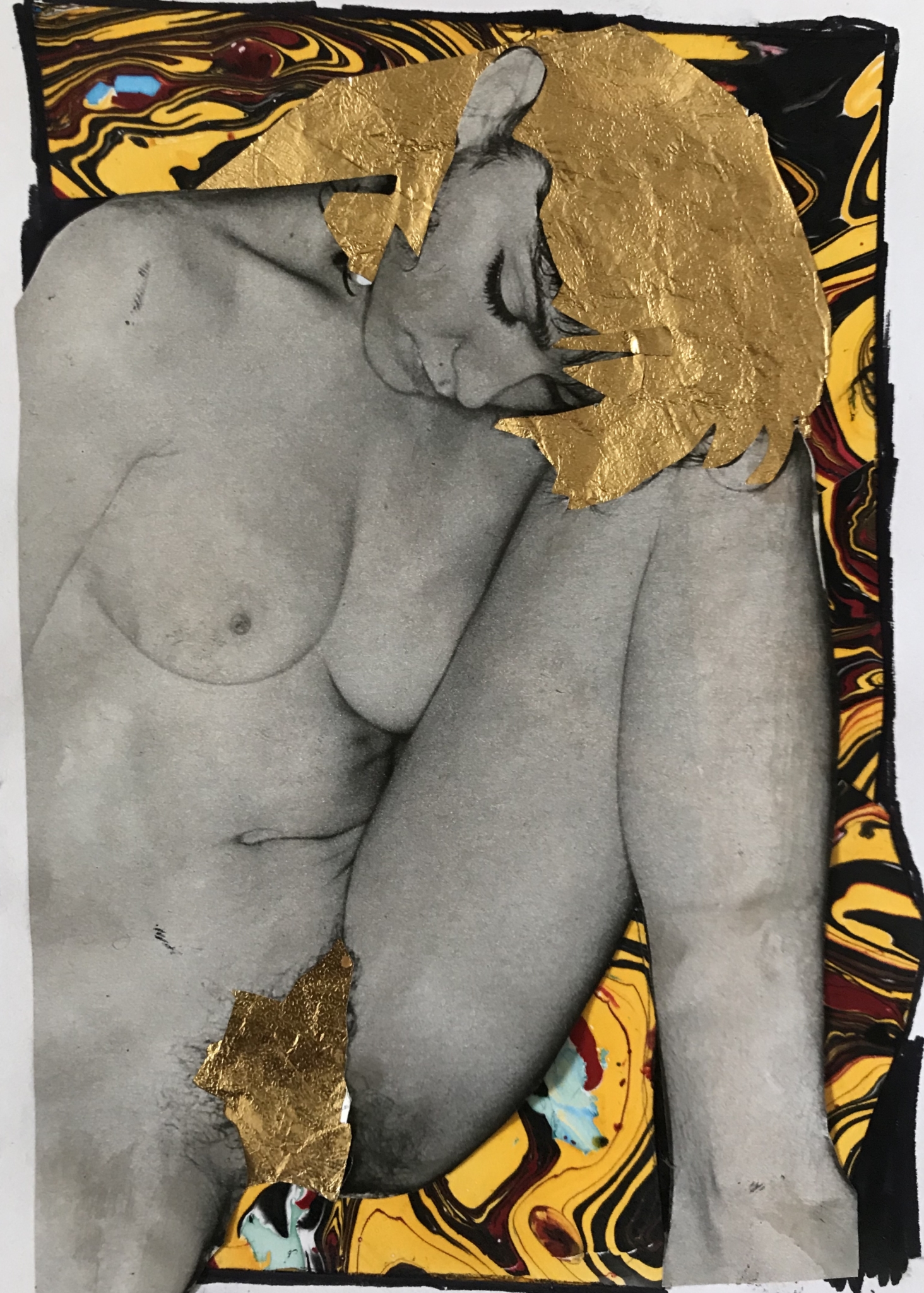

The next section of the exhibition is The Senses, and focuses on the human form. It emphasises how despite physical differences and that which is considered ‘unnatural’, as humans we are all united: ‘we all share the same five senses, the same pain’. Minna Ford’s Golden Stigma adds a sense of victory or agency to hyper-sexualised images of women, the artist questioning what is ‘natural’ about the stigmatisation of body hair. She covered a nude image of Madonna with recycled gold paper from an Easter egg to emphasise this. As put by the artist: ‘female nudity is not always sexual or submissive’, and therefore should not be depicted as such. This work is displayed alongside a poem by Manasvini Moni, the two working together to tackle the bizarre supposed correlation between hairlessness and female beauty: ‘It seems that my hair has multiple identities. / Wherever she goes, she’s seen differently.’ Thomas Peach’s pencil drawing, No mother: woman and doll, stood out to me within the show as a whole. The artist used a traditional composition to lure the viewer into thinking that this was a typical representation of motherhood. However, as suggested by the title, and by the female figure’s absent forwards gaze, the narrative of this image is not typical but becomes increasingly haunting the more it is unpicked. Suzanne van Noordt’s block-print Skeleton Man also struck me as an interesting interpretation of this theme. The artist explains that she was drawn to this technique as ‘it’s effectively trying to create a face by carving holes into it’. I liked how the aggression of this method juxtaposed the typical delicateness of a human face.

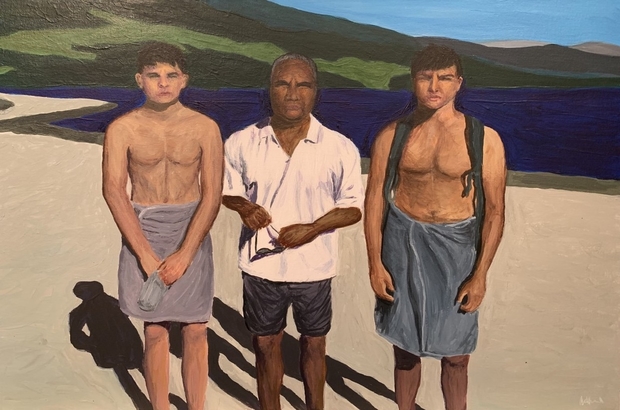

The final section of the exhibition is titled The Interactions and focuses on the intervention of man on the natural landscape and other species that embody the earth. Gabriel Ing’s untitled photograph uses a linear composition to demonstrate how ‘there is no truly native countryside left’, with manmade elements such as power lines encroaching on what was previously a pastoral space. Ida Ahmad’s painting Boys at the Beachstood out to me in this section also. Based on a family photograph, the items the boys wear such as backpacks and towels contrast with the natural landscape, the traditional style of this work further enhancing this juxtaposition.

Overall, especially in a time where our access to exhibition spaces is limited, I found the eclectic mix of works to be absolutely wonderful to click through. The variety in the artist’s engagement with the theme was particularly refreshing, with interpretations of ‘naturality’ and ‘un-naturality’ encompassing a wide range of different topics, from the natural landscapes of the earth and of human bodies, to unnerving and unusual scenarios which confronted the viewer.

UCL Art Society’s Virtual Exhibition Natural/Unnatural can be accessed online via the following link: https://uclartsocexhibitio.wixsite.com/2020.

Featured image: Ida Ahmad’s Boys at the Beach, image courtesy of UCL Art Society.