SONIA CHUI reviews Opal Fruits at VAULT Festival.

Opal Fruits promises to deconstruct stereotypes of working-class women in an exploration of, as the play’s description boasts, ‘the fetishisation of the feral female.’ Difficult to condense and categorise, the play relies heavily on audience interaction, with Holly Beasley-Garrigan creating an immersive experience that prods the audience to rethink questions of tokenism, the misappropriation of working-class culture, and narrative ownership. By telling the stories of several different women, and blurring the lines between public and private, Beasley-Garrigan addresses the tension between the depiction of working-class women as ‘female vice’ and the ‘void’ which these unsupported women face every day.

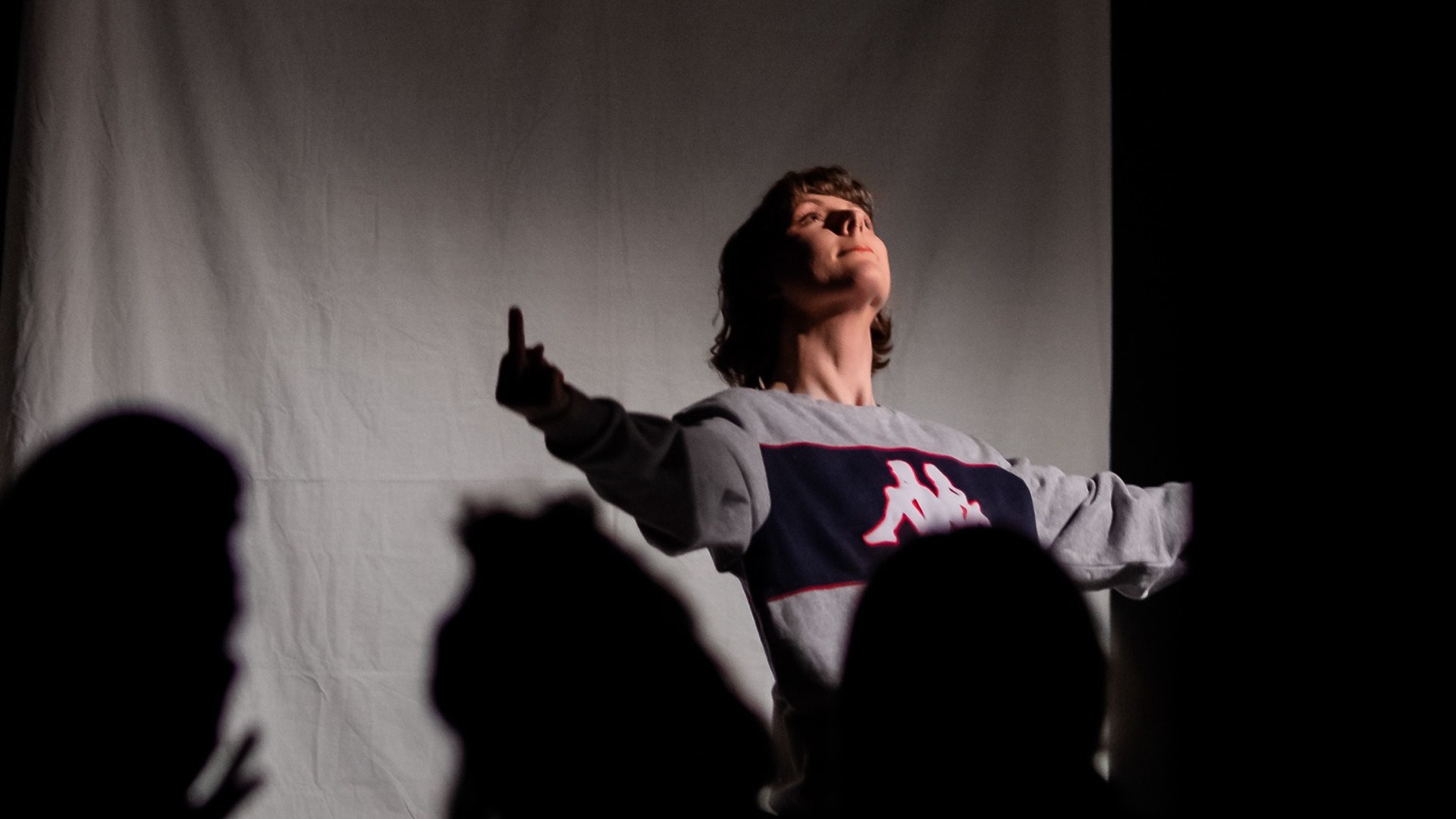

The tone of Beasley-Garrigan’s experimental play is encapsulated by the set and production design. As the audience finds their seat, drum and bass music can be heard, setting the scene of a rave. The set is covered in household necessities, a messy pile of nineties inspired tracksuits and graphic t-shirts, a noticeably makeshift bedside table with a band t-shirt used as a tablecloth, and a white prom-dress hung up on a light bar. Beasley-Garrigan stands behind a bright pink bedsheet, printed with a Jacqueline Wilson-style character. She declares that she’s completely naked and invites an audience member to help her pick her outfit from the pile of clothes. She continues to narrate her characters with consistent audience participation.

The title Opal Fruits itself references nineties culture, the chewy sweets connected to socio-economic freedom: ‘confectionary has no class, except for Lindt…which is posh as fuck.’ Doused in double-meaning, the play’s title is additionally used to characterise each woman, with each one given the pseudonym of ‘opal’ to protect their identity. Beasley-Garrigan retells each woman’s story in the third person, using her space to provide a platform for these women to speak themselves, rather than speaking for them. At one point, she raises the question, ‘what stories are even mine to tell anyway?’

The play is most poignant when Beasley-Garrigan delves deeper into its experimental concept. She is ever conscious of the types of socio-political issues she tackles: ‘Hands up who’s bored of white people making sentimental autobiographical solo shows that use direct address, spoken-word, and gritty clichéd accounts of other people’s struggles for the entertainment of the middle classes.’ While Beasley-Garrigan states that the play does not attack urban gentrification, it certainly attacks hypocrisy. She criticises edgy hipster ‘knobheads’ who appropriate working-class culture but also ‘brag on poor people.’ She states that ‘Craig David ain’t garage’ and that there have been women who have been wearing Kappa tracksuits and Ellesse sweaters ‘unironically’ since the nineties. She questions donning the working-class trope when she is no longer struggling, profoundly asking ‘How the fuck did I become part of the problem?’ The actor shows herself to have a footing in two worlds but not truly belonging to either. Further probing the socio-political status of working-class women, Beasley-Garrigan remarks how some of these women felt that they did not feel ‘socially significant enough to even be part of the middle-class.’ These moments raise questions as to who claims narrative ownership and how to go about enacting such stories, especially ones that aren’t quite your own.

Further illustrating the divide between social groups, Beasley-Garrigan uses a ‘nineties analysis of the material woman,’ demonstrated through the telling of ‘your mum’ jokes. The idea tends towards crudeness: ‘your mum’s so poor when she goes to KFC, she has to lick other people’s fingers’ receives a cackle from the audience. However puerile, it’s an effective moment when the play mingles comedy with sincerity. The jokes become increasingly despairing, before the audience realises that Beasley-Garrigan is criticising those who make such jokes that disregard the struggles of women from underprivileged backgrounds.

Although Opal Fruits proposes thought-provoking ideas, the presentation of the different women’s voices is structurally disjointed and becomes confusing. Jarring transitions occur too quickly without enough context, muddling the scenes randomly. Due to this, it can take a while to differentiate between Beasley-Garrigan as herself and Beasley-Garrigan representing different women. This is not helped by the speedy dialogue dense with imagery, often leaving the audience struggling to fully appreciate the narrative. Having said this, what the play lacks in coherence, it makes up for in its sincere message. Balanced between comedy and poignant self-justification, Beasley-Garrigan effectively strikes an emotional chord in using the play to amplify unheard voices. Layered with flamboyance, nineties nostalgia and British political humour, Opal Fruits prods and provokes, with an engaging actor at its core telling stories that need to be heard.

Opal Fruits ran at the VAULT Festival from 23rd – 27th Jan. Find more information here.

Featured image courtesy of Alex Gent.