ARIANA RAZAVI contemplates the enduring beauty of Rilke’s poetry.

I first met Rilke in a world literature class aged sixteen, in the poem ‘Autumn Day’, on an autumn’s day. It captivated me for a reason I am still unsure of, but was what held me firm in my desire to read literature. The symbolism and lyrical devices were not too complex for my untrained mind, yet they were beautiful and moving. I think that is how I would still describe Rilke now, having read much more of his work that stems beyond the realm of poetic verse.

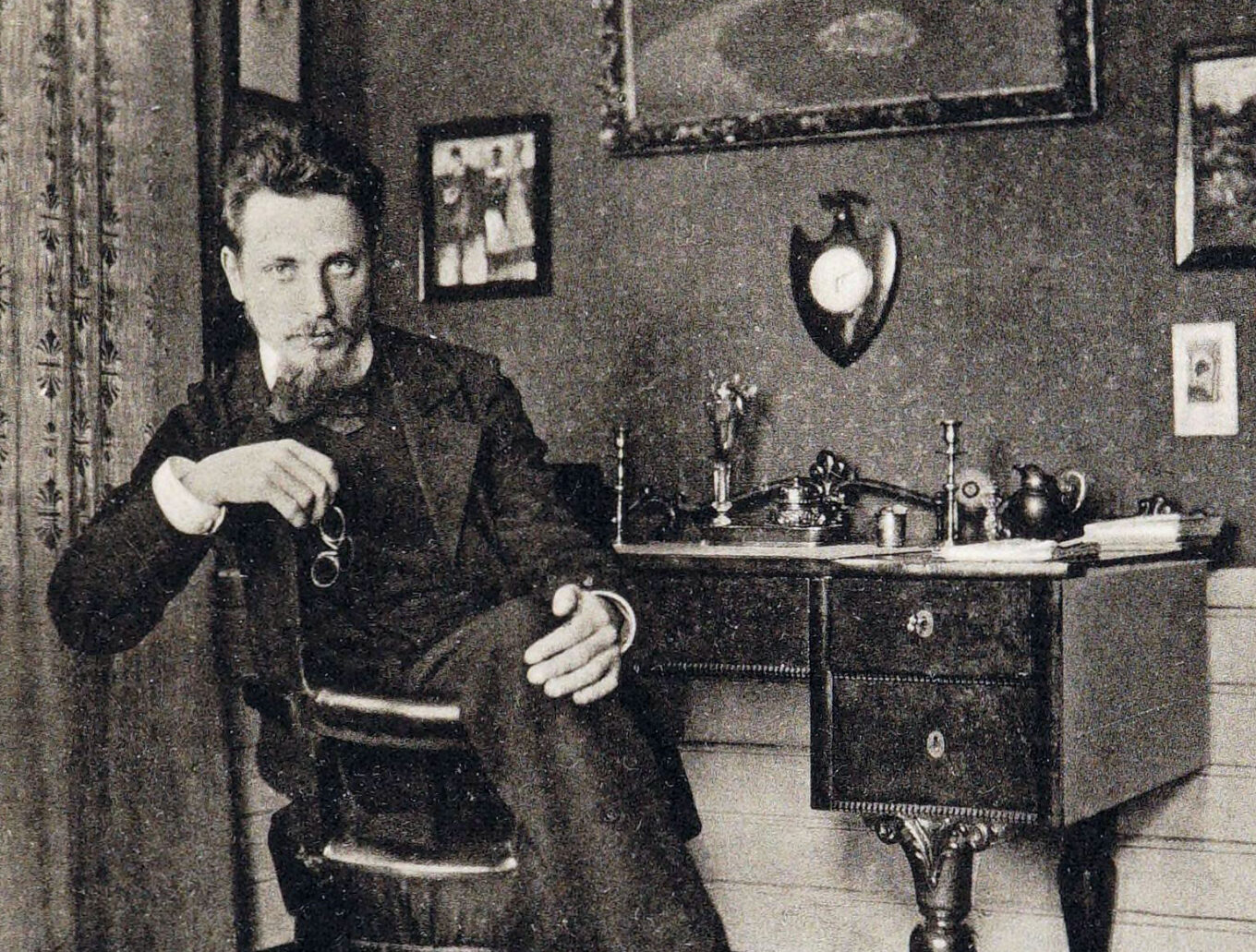

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) was a Bohemian-Austrian poet and novelist, who is most well-known for his contribution to the German literary canon. Rilke wrote on the cusp of the traditional and modernist movements in Europe. This is very clear in his writing, which spans from aesthetic descriptions of nature to human suffering and solitude, often combining these in subtle ways in his verse. Rilke was considerably influenced by philosopher Nietzsche, who led Rilke to enter the sphere of existential writing surrounding individuality and the nature of life and death.

Rilke’s ‘Autumn Day’, from the collection The Book of Images, reflects in a fairly simple way on the profound concept of time. It illustrates how the passing of time manifests itself in contrasting ways in the natural and human spheres of existence. I was deeply moved by Rilke’s description of the passage of time within nature which, as circular and continuous, is a source of hope, of sweetness. As an angsty teen, and frankly, as anyone existing in this tumultuous twenty-first century reality, constants are a crucial solace. This reflection made me view time in a different light, even as the dark days of winter emerged.

Many of Rilke’s poems touch on universal human experiences and are almost philosophical in nature. ‘What Survives’ can be read as an inquiry into suffering and survival; ‘To Music’ a reflection on the purpose and effect of music, and how it moves us. It reads: ‘You stranger: music. Space that’s outgrown us, heart-space’.

Though I could go on about Rilke’s deeply moving and quite fascinating inquiries into human existence in the form of verse, he is best known (at least in the English-speaking world) for a collection of ten letters published posthumously under the title Letters to a Young Poet. These letters, deceptively addressed to nineteen-year-old budding poet Franz Xaver Kappus, are timeless reflections on art, love, pain and the human condition itself. The letters are candid expressions of honest advice. Rilke writes in a way that is self-reflective yet also didactic, captivating his reader. It is a wonderful short collection of profound life advice.

It seems redundant for me to articulate the potency of his words, which ring relevant to young readers even today, so I will leave you with some of my favourite excerpts.

On time, a quotation which reads differently following nearly an entire year of lockdown:

‘These things cannot be measured by time, a year has no meaning, and ten years are nothing. To be an artist means: not to calculate and count; to grow and ripen like a tree which does not hurry the flow of its sap and stands at ease in the spring gales without fearing that no summer may follow. It will come. But it comes only to those who are patient, who are simply there in their vast, quiet tranquillity, as if eternity lay before them. It is a lesson I learn every day amid hardships I am thankful for: patience is all!’

On criticism which, as a philosophy student, becomes more and more relevant the further along my degree I get:

‘And your doubt can become a good quality if you train it. It must become knowing, it must become critical. Ask it, whenever it wants to spoil something for you, why something is ugly, demand proofs from it, test it, and you will find it perhaps bewildered and embarrassed, perhaps also protesting. But don’t give in, insist on arguments, and act in this way, attentive and persistent, every single time, and the day will come when, instead of being a destroyer, it will become one of your best workers–perhaps the most intelligent of all the ones that are building at your life’.

On sadness, and its transformative effect, Rilke writes:

‘You have had many and great sadnesses, which passed. And you say that even this passing was hard for you and put you out of sorts. But, please, consider whether these great sadnesses have not rather gone right through the center of yourself? Whether much in you has not altered, whether you have not somewhere, at some point of your being, undergone a change when you were sad?’

Finally, with these words Rilke closes his tenth letter. I find them comforting now more than ever:

‘I am glad, in a word, that you have withstood the dangers of slipping into all this [art], and that somewhere you are living alone and courageous in a rough reality. May the year to come maintain and strengthen you in it’.

Featured image source: Britannica.com