MATILDA SYKES explores the legacy and music of The Incredible String Band.

I came to like The Incredible String Band much the same way I came to like beetroot: slowly. My dad used to play them during car rides – I would grimace and quietly wonder how he could enjoy such weird music. There was, however, one track I liked: ‘The Hedgehog Song’. A hedgehog shadows the singer’s life, warning him ambiguously that, despite his best efforts, he will never ‘learn the song’. This was their biggest hit. As a seven-year-old, the story primarily appealed to my nascent infatuation with rodents (though research informed me that hedgehogs are in fact classed under the mammal order Eulipotyphla, not Rodentia). Then, as I grew older and began to flirt with lyrics, I recognised the song traced the man’s lifelong inability – despite flings and near-marriages – to find a ‘girl to love’.

Recently, my dad cleared out the attic and unearthed his old records. Lots of ISB popped up. While the sorting process began we played a few, and I was startled at the way the band demanded my attention. The ISB requires active listening in a way few artists and bands do – which is what I think makes them brilliant. You have to stop and focus your ears. Over the past couple of months, many people have understandably found comfort in old music to remind them of better (or worse) times. But we might also use this time to discover new music, even if it’s new-old music. Remembering is good but experiencing is better – and the ISB are an experience.

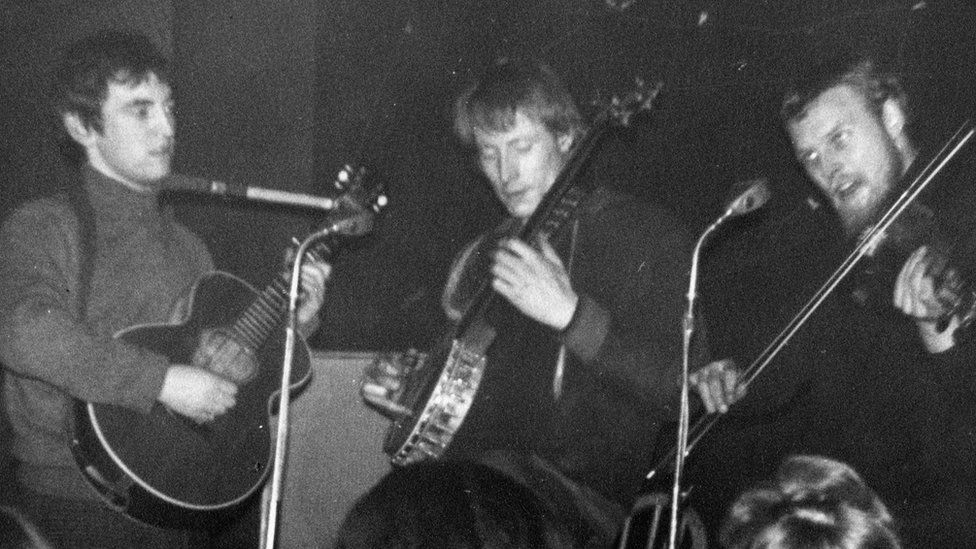

The ISB are a Scottish psychedelic folk band that formed in 1966 in Edinburgh. Originally, the group consisted of Robin Williamson, Clive Palmer, and Mike Heron. Palmer left after the first album, but the split was actually good news for ISB’s future. Heron continued to gig in Edinburgh while a prodigal Williamson travelled to Morocco, seemingly with no set plan to return, but lack of funds brought him and a variety of Moroccan instruments back to Edinburgh. It was this experimentation with instruments and styles from other countries that ultimately gained the band success and a cult following. They were never chart-toppers but their album sales were strong; the ‘album experience’ was, and still is, key. But I will admit that listening to a full album of theirs first-time is plunging in the deep end. Most of us no longer listen to albums in full anymore. Occasionally, we might put aside an afternoon for our absolute favourite artists, but largely speaking we move blithely from song to song. Nevertheless, the benefits of listening to the full album are obvious enough – we can often gain a clearer sense of the artist’s intentions while deepening our own understanding or connection to the album.

Those that describe ISB’s style as ‘eclectic’ are either feeling lazy or trepidatious; I do not blame them. Tracing all the instruments and styles would be a knotty and unavoidably erroneous task. Moroccan, Indian, Afghanistani and Bulgarian styles and instruments merge with a folk base to create an entirely new sound: ‘We kind of invented this kind of music we wanted to listen to’ says Heron, in You Know What You Could Be: Tuning into the 1960s (2010). Traces of reggae and Celtic music are mixed with bluegrass and folk, while Williamson’s often atonal or monotonal vocals evoke religious chanting. You will have to hold your nerve to begin with.

Heron and Williamson both freely inserted apparently random and unrelated sections in their songs that frequently pivoted the tone, style and tempo, requiring the listener to continually readjust their ear. Needless to say, this freedom of structure does not always result in easy – or even pleasant – listening. Often we cannot foretell the song structure (which, admittedly, we normally can), and the effect is to make a listener twitchy. Starlings twist and turn individually but ultimately move as a murmuration; ISB’s songs drift apart to the point of unsalvageable disarray before rejoining. They travel as a unit.

Suspension of prediction and acceptance of inharmoniousness as harmony brings great rewards. Robert Christgau pithily captures the common response to the band in Christgau’s Record Guide: Albums of the Seventies (1981): ‘Way back in the 1960s I tried to figure out whether these acoustic Scots were magic or bullshit and concluded that they were both.’ Perhaps this is fair enough. They are an outfit that clashes so badly it sings – and you need to give your eyes time to adjust (maybe you are thinking, Must I?, and no, I guess you do not, but The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Led Zeppelin and many others are on my side).

If you can make it through the first few listens you will begin to recognise what they are really about: organised chaos. Apparent dissonance is counterpoised by lyrics that benefited from the mixture of Williamson’s poetic vibrancy and Heron’s porousness. Williamson’s lyrics reach their apex in ‘October Song’ (1966). Bob Dylan famously described the song as ‘quite good’ in an interview with Sing Out magazine (which is actually rather high praise). Here are some of my favourite verses:

Beside the sea | The brambly briars, in the still of evening, | Birds fly out behind the sun, | and with them I’ll be leaving.

When hunger calls my footsteps home, | The morning follows after, | I swim the seas within my mind, | And the pine-trees laugh green laughter.

I met a man whose name was Time, | And he said, ‘I must be going,’ | But just how long ago that was, | I have no way of knowing.

Sometimes I want to murder time, | Sometimes when my heart’s aching, | But mostly I just stroll along, | The path that he is taking.

The simple lyrics are vivified by imagery that is coaxing rather than delineative. The susurrating laughter of the pine-trees matches the very best of Robert Frost’s forest poetry, while the chilled-out evocation of Time resonates tonally with Shakespeare’s own formidable personification in The Winter’s Tale. Overall, the feel is of sorrowful resignation but the key change on ‘Sometimes I want to murder time’ nods to the song’s latent angst, which we are forced to acknowledge in his heart’s ‘aching’. ‘The Half Remarkable Question’ (1968) is another example of the band’s lyrical precocity with phrases like ‘elephant madness’ and ‘freckles of rain’. It is also hard not to admire a band that confront such big, potentially trite questions as:

Oh, it’s the half-remarkable question | What is it that we are part of? | And what is it that we are?

and manage not to sound pseudo-philosophical and whiny. They get away with it because a) it’s the sixties and b) the natural reverb of the sitar expands the track’s sonorousness to parallel the expanse of the questions (Cool fact: ISB flew into Woodstock in a helicopter with a frightened and sitar-gripping Ravi Shankar).

Heron’s lyrical talent often feels harder earned than Williamson’s. However, the track ‘Flowers of the Forest’ (1971) on Heron’s solo album Smiling Men with Bad Reputations reflects his absorption of Williamson’s poetic flair. In it, a third-party commentator commiserates and comforts a heart-broken woman. The speaker’s distance is what makes the song tragic as well as uplifting; the generous speaker accepts his minor role without being embittered.

Heron’s earlier lyrics reflect a less philosophic, contemporary engagement with the 60s in Mercy I Cry City. The frantic harmonic blow and draw augment the lyrics, ‘Send another carriage chugging down your chokey tube | I hope it makes you happy ’cause it don’t do my health much good’, while a maddening pipe underscores ‘You slowly killing fumes now squeeze the lemon in my head | Make me know just what it’s like for a sin drenched Christian to be dead.’ Fifty-three years later the song has only gained in pertinence.

ISB reached their experimental apogee in the thirteen-minute ‘A Very Cellular Song’ (1968) which blends musical styles as varied as East Indian incantation, Celtic mysticism and Bahamian funerary music. Kazoo, harpsichord, pipes and handclaps interweave chaotically. I struggle to get the whole way through this track; the kazoo threatens to make the whole thing feel too much like a joke. And an ode to mitosis from the perspective of an amoeba can be difficult to find even fractionally relatable. But just as the listener begins to get the idea, ISB reorient: you are now listening to a bewitching incantation. ‘Keep up!’ they laugh. Writer Dan Lander describes the song as ‘a powerful range of human emotion through pain and joy and back again’ in Music Is Rapid Transportation: From the Beatles to Xenakis (2010). Or, take songwriter Heron’s word; ‘All it was was a trip’ (Making Time, 1999). Either way, it’s worth a listen for its sheer creativity.

If this article is anything, it is proof that I do not know how to describe The Incredible String Band. However, listening to the ISB has given me an appreciation of the benefits of frustrated listening. They are one of the biggest cases of ‘get back what you put in’ (which is why now is the perfect time to listen, when we can put in more). Frustrated listening, by definition, engages you in a way that ‘easy’ music often cannot, and engagement tends to be a good thing. The cacophony of musical styles and instruments will not waste themselves on distracted listeners but will pile gifts onto the attentive ones. But even if you simply do not like them, they will push you to consider your musical preconceptions – notions of genre, tempo, language, order, style – in a way few other artists, bands and beetroots do.

Featured image courtesy of Matilda Sykes.