TEREZA BLAHOVA reviews Artemisia at the National Gallery, and considers the importance of representing narratives that have typically been excluded from art history.

trigger warning: discussion of sexual assault

At its core, Artemisia at the National Gallery is a compelling exploration of a female artist still woefully left out of much of the art historical canon.

The exhibition starts off strong, immediately framing the works within a female perspective. I found myself drawn to Susanna and the Elders (c.1610), a subject revisited by the artist several times, in which the eponymous character is clearly depicted naked as opposed to nude (a distinction between the two made most concisely by art historian John Berger). She is made vulnerable through the gaze of the lecherous Elders in a strikingly uncomfortable way. The viewer is led to sympathise with Susanna’s discomfort at being seen, as opposed to being complicit with the Elder’s objectification of her. Gentileschi’s masterful painting of facial expressions, in particular, moves her women from being sex objects existing solely for male aesthetic enjoyment and consumption, to being real women with thoughts, feelings, and agency over their situation. An intermingling of disgust and fear is palpable on Susanna’s face; one can infer that this feeling of being harassed by men comes from the artist’s personal experience, as it is so true to life it could only have been painted by someone who intimately knows what it feels like.

Indeed, another success of this exhibition is the sensitive way in which it provides context for Gentileschi’s life and work. Subject to a rape at seventeen years old, many of the artist’s works have understandably been impacted by this event. A manuscript from the rape trial is provided in the very first room. Initially, I was afraid that this would cause the exhibition to get bogged down with biography, as female artists tend to get over-contextualised compared to their male counterparts, shown purely in the shadow of some tragedy while men get to be celebrated based purely on artistic merit.

Thankfully, Artemisia treads this line carefully. The timing of this information within the exhibition as a whole, as well as the way in which the incident is talked about, achieves a range of things. The rape is not made into a focal point; it has to be mentioned, as uncomfortable as it may be, but it is neither fixated on nor brushed off to the side. This ultimately allows Gentileschi’s work to speak for itself, the context enhancing the viewer’s understanding of her oeuvre rather than overshadowing it. If anything, its decentring makes Gentileschi’s artistic achievements all the more impressive, it being that women of the time were rarely allowed to tell their own stories, from their own perspective, without being suppressed by the patriarchy. She is shown to be a significant exception to many rules.

The exhibition moves in chronological order through a series of basement rooms in the National Gallery, culminating with works she made in London, which feels like a bit of an Easter egg ending. I agree that this chronological curation is the best way in which to view Gentileschi’s work, as she revisits certain themes and subjects at various points throughout her career, and I thoroughly enjoyed being able to track her development as an artist. I mentioned Susanna and the Elders previously, a subject which is shown three times in the exhibition. By the third iteration, Susanna appears much surer of herself, less vulnerable and defenceless than before, perhaps representative of the artist’s own growth and increased confidence in her personal life. The scale of the paintings also becomes increasingly ambitious; Gentileschi’s women grow bolder and stronger as the artist fully develops her impressive visual storytelling and manual techniques.

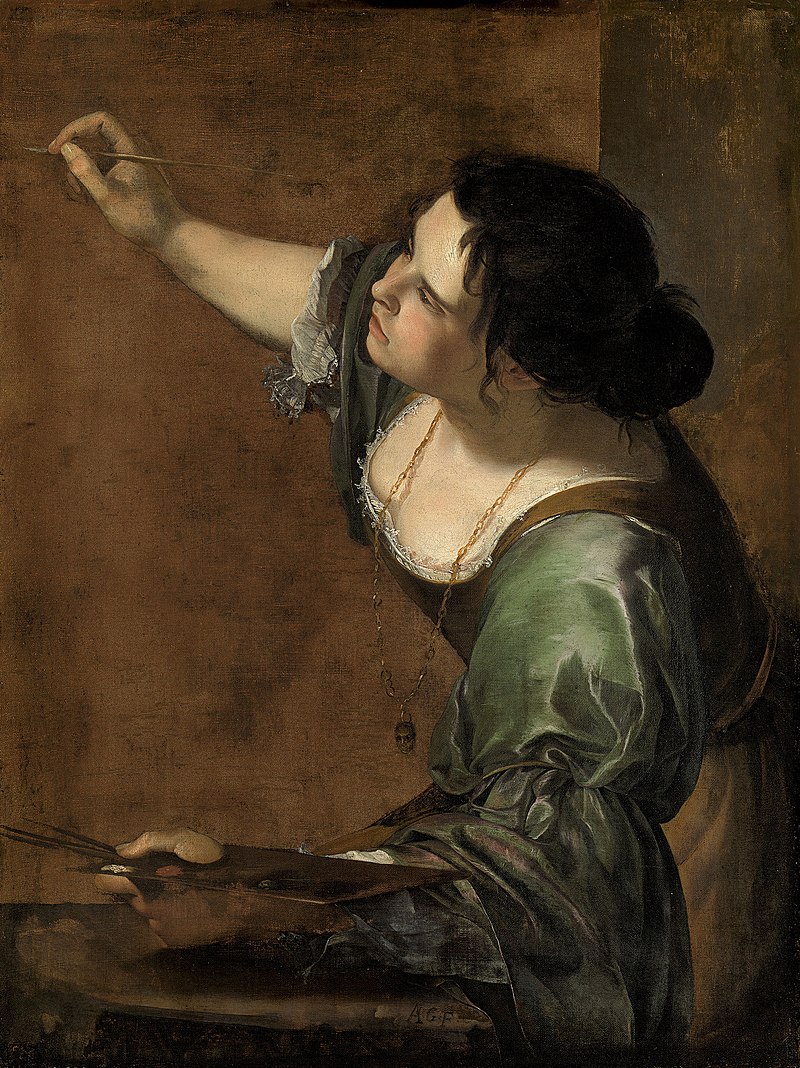

The exhibition very much picks up speed throughout the latter half; we have been introduced to the artist and are now presented with a wide array of beautiful, richly coloured paintings through which the artist comes into her own, away from her father’s initial stylistic influence (Orazio Gentileschi, a famous artist of his time). This culminates with a painting in the last room of the exhibition, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (1638-1639), in which Gentileschi paints herself painting. This self-portrait is a bold statement: it was incredibly rare for a woman to be an artist during her lifetime, let alone a celebrated one. Gentileschi visually inserts herself into history, on par with any other male artist of her generation and beyond. The way in which she signs several of her paintings is also a testament to her determination to write herself into history and not be forgotten: the artist makes her signature a direct visual aspect of the overall narrative, for example, in an open book or on a scrap of paper on the floor, rather than just in the corner of the canvas.

It is sad that the celebration of a strong female voice is still a relative rarity among art exhibitions. My primary feeling throughout the exhibition was one of refreshment – seeing my own female body reflected in an identifiable way, allowed space to simply exist in various states. Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (1623) was another stand out piece. The tightly cropped composition captured the intricacies of female sensuality and sexuality existing outside of the male gaze. There is nothing inherently sexual about the pose of Mary Magdalene in the image, instead giving the viewer an insight into the subject’s state of mind, and humanising a figure heavily criticised, almost demonised, throughout religion and history. Gentileschi always paints her women with a sympathetic and almost naturalistic touch, which is very evident here. I truly believe that only a woman can paint other women in such a thoughtful, evocative, and respectful manner. This is not to say that Gentileschi has a ‘feminine style’, but rather one which avoids reinforcing female stereotypes, because lived experience has proven them to be false; the style of an ‘insider’ to the female psyche.

I found that the deep, warm colours of the walls, relatively small rooms and low ceilings enhanced the paintings, providing an atmosphere of intimacy to the exhibition. These features allowed the viewer to connect more deeply with the work, rather than being overwhelmed by it. I was also impressed by the overall accessibility of the exhibition, with plenty of seating available, and a large volume of plainly written information and analysis for those less familiar with Gentileschi’s work. I’ve been to several exhibitions in the past that have had an air of gatekeeping around them; information on the walls written in obscure language and with needlessly big words, or sometimes no information at all. The sense I got from Artemisia was that it is an exhibition trying to teach you something, rather than scare you off with the pretentiousness and exclusionism that is too common in the art world.

My only gripe with Artemisia is the prohibitive cost of tickets, and the overcrowding I experienced during my visit. I will, however, choose to take the exhibition’s evident popularity as a positive sign, that the voices of marginalised women are finally starting to be heard and appreciated by the wider public.

Artemisia will reopen at the National Gallery on 03.12.20.

Featured image: Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes, c.1612-1613. Oil on canvas, 159 cm x 126 cm. Image source: Wikipedia.