AMANDINE COUOT-GARIBAL reviews Aubrey Beardsley at Tate Britain.

In the midst of the pandemic, there is something strange about stepping into the exhibition of an artist who died too young from a lung disease. Death becomes an overbearing thought, as visitors sanitise their hands, adjust their masks and awkwardly wander around the one-way exhibition, mindful of other gawkers, trying to make the most of Aubrey Beardsley’s detailed prints and ink drawings.

All throughout the exhibition, Beardsley seems to be playing with Death and Time. In capturing his friends, scenes of romance and sexuality, and even dramatic scenes from Oscar Wilde’s Salome, he relieves the air of its heaviness, with the light-handed yet deliberate confidence of his black lines. If it wasn’t for the masked crowd of this sold-out show, I could almost forget the guilt with which we move around; I would not think about politely smiling and stepping aside to ensure everyone can have a look at the works, but rather indulge in gazing at the masterfully placed dots, the hidden motifs and the characters’ flirty gazes.

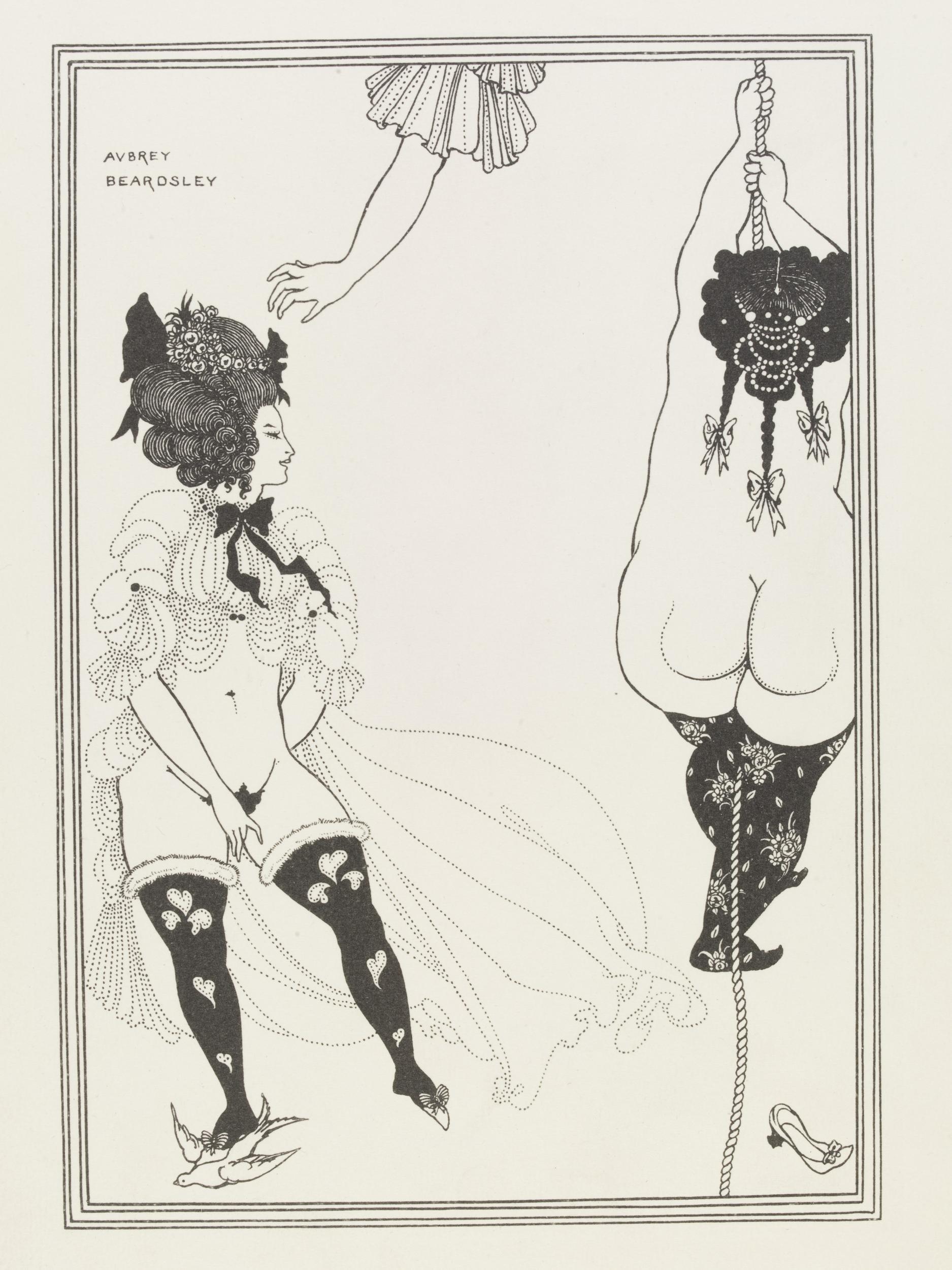

Aubrey Beardsley (1873-1898), most famous for his monochrome ink drawings, particularly his illustrations of Oscar Wilde’s Salome, was a self-taught artist who tragically passed away at twenty-five from a lifelong struggle with tuberculosis. In spite of, or maybe because of the looming early ending of his life, he produced more than a thousand drawings over his seven-year-long career.

The exhibition does not seem to have a clear angle, other than its being the largest Beardsley exhibition in 50 years, which would have mattered if the artist and his work did not already say enough on their own. With Beardsley, there is no need for an overworked delivery. The exhibition is very extensive, with works spanning from the beginning of his career to the more liberated end of his life, during which he chose to explore erotic themes from Ancient Greek and Roman plays. Where, at times, the exhibition began to drag on a little bit, I reminded myself that this should only heighten the excitement of reaching another room and discovering a new stage of Beardsley’s life and art, a new facet of his short career.

There were some issues as ever with the curation, which is a problem that I have encountered many times at Tate Britain. For one, while I appreciate the signature look of the museum’s coloured walls, clashing with the classic White Cube style of many art institutions, I often find that it distracts from the works on display, taking away their poignancy. This exhibition was no exception. While these coloured walls may be striking in an installation view picture, they make it harder to engage with each work; the eye finds itself blinded and confused by the dark blues, greys and pinks that should instead be pushing Beardsley’s works forward. This is a recurring and disappointing feature, which I also had a problem with at Tate Britain’s William Blake exhibition back in January. One would have to try hard to obscure Blake’s stunning ink drawings, despite them retaining so much of their vibrancy over the years.

There is also the eternal problem of accessibility, pointed out by my partner, which sees labels written in light grey against a dark grey wall. This means that the text is simply indistinguishable for anyone who is either looking from afar, or who is partially sighted.

While this issue of accessibility is specific to the curatorial choices of this show, I cannot write about such a grievance with the Tate without making the connection to its director’s recent actions and the ongoing strikes by Tate employees. Despite receiving a hefty seven million pounds in government funding, and the fact that exhibitions have been consistently selling out, Tate director Maria Balshaw made the decision to let go almost half of the London staff, most of which are low-paid and from BAME backgrounds. To claim diversity in their shows (from the Queer and Now festival to Zanele Muholi’s upcoming solo show), while unnecessarily putting employees in precarious situations during a global crisis, is a violently performative move on Tate’s part, and it would be wrong to gloss over it for the sake of comfort.

Tate’s ethics aside, this is an incredible exhibition. There is a surreal quality to Beardsley’s drawings, and it is absolutely worth stopping for a closer look: the closer you look, the more you see. From hidden phalluses to spider webs, it feels like the artist is calling upon the spirits of artists such as Hieronymous Bosch, evoking the same hypnagogic atmosphere Dali achieved in later years, all executed with a purity of lines found in no one else.

Whilst his style is certainly reminiscent of his Art Nouveau contemporaries such as Alphonse Mucha, Beardsley is truly unique in how he creates depth and texture in all his illustrations. His lines carry a childlike simplicity, yet overall his works possess the knowledge and confidence of someone old enough to deliberately provoke.

Beardsley’s power lies in the hybridity of his work and his life. The artist apparently navigated all social circles with ease, befriending the famous and highly regarded, but also found wonder in the seemingly mundane life of well-to-do Victorians. The contrast between the large number of quotidian drawings he produced and his longer, more studied commissions (such as Le Morte D’Arthur) shows the breadth of Beardsley’s genius: it is not self-absorbed, nor just a reflection of his mind. Rather, it flirts with reality, offering a new lens through which to look at a sometimes dull Victorian world.

His was not a selfless quest for beauty, and to say that Beardsley made l’art pour l’art would be a mistake: Beardsley wanted fame, notoriety, and he had the wit and talent to match.

There is something comforting, reassuring about seeing sexualities depicted as openly as Beardsley did in Victorian times. As a queer person navigating heteronormativity, seeing historical depictions of non-normative (by ‘normative’ I mean ‘restrictive’) interactions puts me at ease and brings me comfort in the knowledge that sexuality has always been fluid, and will always remain so. Moreover, seeing this aspect of my identity acknowledged in such a show – that of a white, well-to-do, Victorian-era Englishman – brings unexpected glee. It is still rare to see queerness represented free of a fetishising gaze. Beardsley has a playful and flirtatious pen, not a possessive or predatory one.

In fact, I found that the nonchalance with which Beardsley’s women are drawn playing with themselves and with each other, with full ownership of their self and bodies, brought on a rageful desire to recreate this untroubled joy once out of the exhibition.

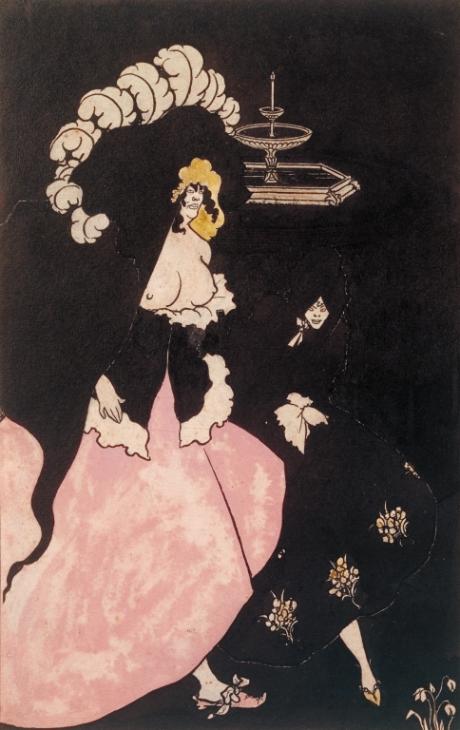

Beardsley shows time and time again that there is beauty in the monochrome. In fact, colour might have just distracted from the purity and dynamism of his lines, and his paintings of friends and loved ones do not conjure up the same effect as his black and white ink drawings.

Ultimately, not even Tate Britain could spoil Aubrey Beardsley. He transcends time and trends. The strength of his art, and what truly draws the viewer in, are his lines; elegant, playful, ever dynamic, infused with life. Aubrey Beardsley lives on.

Aubrey Beardsley ran at Tate Britain from 4th March 202o – 20th September 2020.

Featured image: Detail from Aubrey Beardsley, The Climax, 1893, line block print of Japanese vellum, 34.2 x 27.2 cm. Image courtesy of Studio International.