GEORGE DENNIS visits Estorick Collection Uncut, considering the presentation of abstract, politically charged modern Italian art.

To saunter through galleries on a rainy day is the archetypal London Sunday afternoon. Who hasn’t floated down those wide corridors with self-satisfied awe, coming face to face with iconic images first discovered in Tate calendars and the covers of Penguin Classics? I am proud that our city’s cultural institutions promote a message of democracy and accessibility in being broadly free of charge, promoting a very literal message of accessibility in a field too often characterised by snobbery.

Having several times visited Islington’s Estorick Collection, the country’s only museum dedicated to modern Italian art, I believe it is essential to rethink how we exhibit art at its most abstract and conceptual. The Estorick Collection perfectly curates a breath-taking collection of modern art including the works of famous Futurist painters from Giacomo Balla to Umberto Boccioni, as well as works by Morandi, Giorgio de Chirico and Modigliani. Perhaps the most impressive act of curation in this gallery is the gentle ease set onto the viewer. The sensations of modernity, the early manifestations of Fascism, the metaphysical charting of memory are all heavy themes explored upon the interior walls of the Estorick, yet are made approachable for any visitor.

The gallery’s most recent exhibition, Estorick Collection Uncut, is a thematic journey through the collection’s most iconic pieces, with a special display titled A Still Life: Paul Coldwell in Dialogue with Giorgio Morandi. Both exhibitions are found not in a cavernous Cathedral-like gallery but strung over three floors of a large Georgian town house. The building bridges the gap between the public and domestic spheres, art is respected, and the viewer is comfortable. You are afforded an intimacy with Giacomo Balla’s The Hand of the Violinist (1912), allowed to appreciate motion caught on canvas at your own pace. This piece reflected the Futurist concern for depicting the constant motion of modern, urban existence. Balla incorporated into his paintwork the potentiality that contemporary photography and cinema afforded. Rather than lamenting film’s primacy in visual art, Balla used it to deconstruct the assumed fixity of painting. This is a space where art is venerated but not overly idolised. A space where the likes of Modigliani are met casually at the dinner table, not upon a pristine pillar.

For as well as the lofty themes at play within this exhibition, which unapologetically steps into the realm of the metaphysical, the curator seems to place an equal emphasis on the materiality of the paintings. Take one of the centerpieces of the first room, Umberto Boccioni’s Modern Idol (1911). This enigmatic portrait does not simply sit on the wall but is positioned in the centre of the room. The range of stickers upon its back allows the viewer to trace the painting’s circulation across borders. The art of curatorship is granted equal value with the literal art of painting. The exhibition also highlights the recent research into the potential antique panel Boccioni is thought to have painted onto. Alongside Balla’s violin an infrared image reveals an image of Dusseldorf beneath the layers of oil paint. We are allowed to understand not only what Balla chose to create, but equally what he chose to deface.The exhibition takes an active interest in artistic process and composition, not only allowing the viewer to trace the material history of these great works but stressing the essential Futurist principle of blotting out and tearing down historic cultural institutions and practices.

These ideas unfold naturally within the second installation: Futurism and Politics. The geometric dreamscapes of Giorgio de Chirico lay alongside countless manifestoes and pamphlets, texts that are very much works of art in themselves. Intuitively curated, this installation encourages one to consider the murky boundaries between aesthetic and political theory. The ideological application of Futurist painting could not have been clearer: this was art that was at once untethered from history and yet intimately rooted in ideas of nation building and the preservation of order. Of course one could simply enjoy the material splendour of these pieces; the exhibition does not demand any prior understanding. The curatorship was not oversaturated with information. It is here that one can form their own patterns of interrelation between the works.

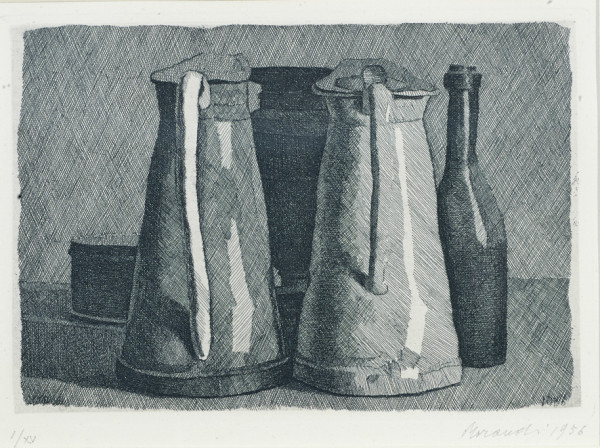

The top floors of the Collection are devoted to the still lives and etchings of Giorgio Morandi. His attention to the everyday object makes his work an appropriate fit for the cosy, domestic atmosphere of this gallery. Finding his collection after climbing the final flight of stairs is like happening upon a stash of family heirlooms in the attic of a beloved relative. Characterised by its sensitivity to light and naturalism of tone, Morandi’s arrangements of objects are instantly accessible but equally perplexing, exhibiting something universally recognisable and yet uncertain. The outlines that police one object’s wholeness from another are consistently under interrogation. The viewer is encouraged to evaluate these very simple spatial relationships much in the same way you would with the metaphysical drawings of Georgio de Chirico.

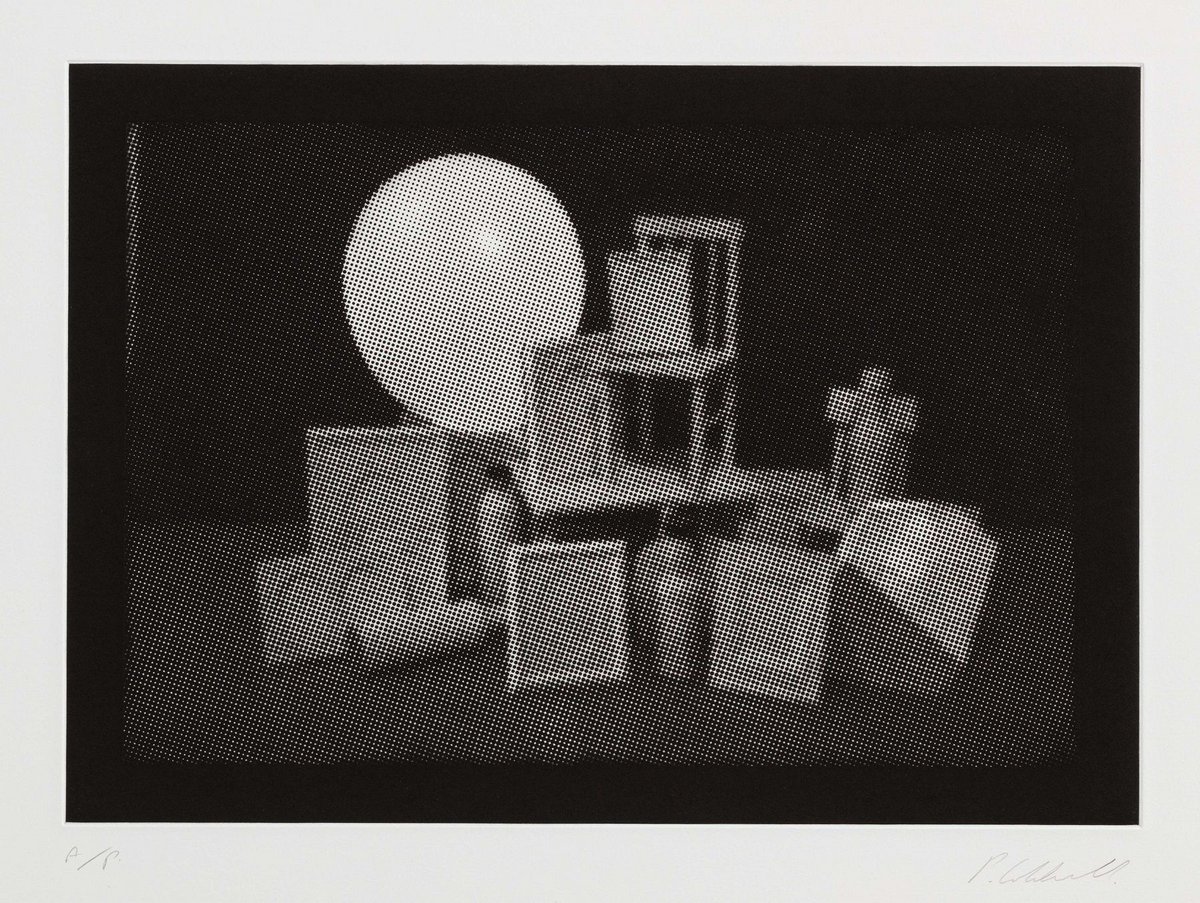

This permanent collection is positioned in conversation with contemporary artist Paul Coldwell, who I had the pleasure to talk to about his practice. His work on display consists predominantly of plaster sculptures of everyday items positioned on the base of a wooden pallet. These sculptures were also the subject of his prints, in which his use of halftone dots seem to speak directly to the cross-hatching of Morandi’s etchings. Like me, Paul Coldwell found that the understated interior of the collection allowed for a far greater appreciation of both his work and that of Morandi’s. Much of Coldwell’s work on display was created during lockdown, something he compares to Morandi’s self-imposed isolation in which he constantly rearranged different groupings of objects. Coldwell’s stripping down of the domestic item into its most basic plastered form plays on the same uncanny dichotomy of Morandi. Like a half-seen apparition, Coldwell’s work seems to draw on a shared past with the viewer, yet its stripping back precise features renders this history uneasy, like recalling a fragment of a dream.

If you have never ventured to the Estorick Collection before, this retrospective exhibition is the perfect opportunity. If the collection is already familiar to you there is every reason to revisit this fantastic panorama of modern Italian art. Having regained many of its borrowed pieces from across the nation, the gallery offers a carefully curated narrative that traces the essential artistic developments within a miscellaneous array of avant-garde movements. Whilst much of the work, particularly that of the Futurist school, is unapologetically abstract, at no point will a visitor be lost in a whirlwind of meaningless, self-serving art terminology. Its content is challenging but at all times comprehensive. The primacy of material beauty is, in my mind, the core principle of this project. Uniting art that lives so much in the realm of the abstract and metaphysical with the cosy intimacy of a domestic setting provides an incredible opportunity for anyone to engage with some of the finest examples of modern Italian art.

Estorick Collection Uncut is open until 19 December.

Featured image: promotional image, A Still Life: Paul Coldwell in Dialogue with Giorgio Morandi. Image source: The Estorick.