ELLA SARAX reviews Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear at the V&A.

Menswear is undergoing a creative surge. It is undeniable that masculinity has taken on a new definition in recent years, seen in the romanticisation of traditional workwear, to oversized and loose-fittings adopted in womenswear. High-end fashion has been particularly impacted, with fashion houses like luxury giant Gucci embracing the shift by favouring androgynous models, and combining their men’s and women’s runways. It is unsurprising, then, that the V&A was keen to curate the subject. Fashioning Masculinities attempts to explore menswear through the ages and, more broadly, the intersection between masculinity and fashion. As someone interested in menswear, I was excited to deepen my understanding of men’s fashion. However, despite the exhibition having great potential, its ambition was lost in its execution.

The first room of the exhibition is promising: a discussion of the ‘ideal male form’ in Greece and Rome, and well summarised histories of various garments, such as the shirt – one of Jonathan Anderson’s delicately crafted organza suits stands out in particular. This initial snapshot of masculinity is filtered through an exclusively Western lens, which I assumed was intentional, expecting equal discussions of menswear in Asia and Africa to follow. Unfortunately, these expectations were never met, which was disappointing given the fascinating differences in both menswear and gender discourses globally. Near the end of the room lurks the first of this exhibition’s wildly bold claims: that Hercules’ exaggerated muscles ‘spawned gym culture’, a strange statement to make with no further exploration. Whilst exaggerated physiques have undoubtedly inspired men’s workouts, ‘gym culture’ also encompasses self-discipline, anger management and brotherhood; reducing this solely to vanity is counterproductive, especially in an exhibition supposedly celebrating masculinity’s many forms.

The next segment of the exhibition is a fast-paced timeline progressing from ancient ideals into the 21st century. It largely consists of portraits of wealthy men, the interwoven relationship between fashion and class, and a rather extensive array of black suits given the relatively small scale of the exhibition. Once again, this collection is purely Euro-American, with any reference to counties outside of these regions mentioned only in relation to their role as colonised nations. Whilst the acknowledgement of colonisation is necessary while discussing imported goods, by not platforming the garments, voices, and traditions of these countries, this exhibition became merely another example of Western curators situating the Global South only in the context of European history. This being said, the exhibition even fails to offer a holistic representation of Western masculinity. There are some moments of refuge, such as the showcasing of a Martine Rose suit, nodding to the designer’s Jamaican heritage, but disappointingly these were few and far between.

Where the exhibition really derails is in its attempt to showcase contemporary menswear. Despite its Westernised focus, the exhibition is virtually devoid of any mention of hip-hop or streetwear’s influence. Considering the starkly visible rise of athleisure, both on runways and through the streets of every major city, this seems out of touch. I found the omission of modern fashion icons such as Kanye West, Tyler, the Creator, and Playboi Carti strange, especially given the inclusion of other garments worn by famous figures, such as Timothée Chalamet’s bedazzled, Haider Ackermann suit (despite its embellishments, this piece was simple, and made no larger statement). The exhibition was curated by Rosalind McKever and Claire Wilcox; as important as it is to have an insight through a female lens, I think the exhibition is missing a critical sense of perspective on menswear and masculinity that perhaps the insight of a contemporary male would have facilitated.

Later in the showcase is a brief nod to the deconstruction methods utilised by designers such as Rick Owens. The brevity of this section again feels like another missed opportunity, given the rise in popularity of ‘anti-fashion’ and avant-garde styles in menswear over the last five years. Pioneers such as Comme des Garçons, Maison Margiela, Vetements, and Chrome Hearts – to name a few – have helped shape a whole new subculture, and were only featured momentarily within displays as a whole. Dramatically distressed garments, flowing skirts, and platform boots adorning fully tattooed rappers such as Playboi Carti and Lil Uzi Vert have created such beautiful contrasts which would have been the perfect dichotomy to be explored in this exhibition. Unfortunately, it seems the most intriguing parts of the exhibition were added last minute and with a begrudging sigh. Speaking of Margiela, the Tabi boot seems an obvious piece to include. Getting men to wear hooven heels as a fashion staple is no easy feat, but it’s one the House pulled off gracefully. This omission, however, is unsurprising in a menswear exhibition containing not one pair of trainers or a nod to sneakerhead culture.

The final three looks are elevated on a table: Harry Styles’ Vogue cover Gucci dress, Billy Porter’s Christian Siriano tuxedo-dress from the 2019 Oscars, and Bimini Bon-Boulash’s finale gown from RuPaul’s Drag Race. Considering Porter’s vocal criticism of Styles being lauded for the same styles which have caused queer people to be mocked for decades, placing the two next to each other with no mention of this discourse was distasteful. It’s upsetting that this takes away from Siriano’s stunningly cohesive dichotomy of a traditional suit and a ball gown: a piece which is a testimony to his craftsmanship, and truly relevant to the discussion of masculinity. Despite my adoration for Bimini, their dress also feels out of place in this position. Drag is performance art which frequently breaks convention in unprecedented ways, from twisting the boundaries of gender to reimagining the human form. Drag deserves its own conversation, not to be used as a way to name-drop a rising icon in the hopes of amassing more visitors. Drag is art and it is performance; the majority of drag queens who identify as men do not wear their drag day-to-day. This gown is a highly sctructured, punk-influenced bridal dress, worn as a drag performance by someone who is non-binary. It has no nod to traditional masculinity. Its inclusion is therefore puzzling, especially considering other looks from Bimini’s catalogue which could have been chosen. For example, their dazzling and revealing Norwich City FC bodysuit, which was a showstopping collision of football hooliganism and female sexuality, could have sparked a conversation on sport and masculinity, and both the beauty and evil in that sphere.

I can understand wanting to include major pop culture moments, however, not only was there no discussion of the impact of these recent pieces, but arguably the majority of these contemporary looks would have already been digested by anyone who had read a magazine in the last year – anyone who had Instagram, even. These huge pillars of pop-culture buzz reinforced by no foundations (deeper discussions, opposing views, inspiration, and impact), leaves the whole exhibition falling flat – these looks felt shoehorned in, right at the end, in a sloppy nod to ‘queer masculinity’ as an afterthought.

Overall, a more diverse curatorial team, including the voices of both male and female designers, editors, artists and so forth, would have facilitated a more rounded, and nuanced exploration into menswear. Additionally, the inclusion of menswear and gender culture from the Global South would have given a deeper insight into the concepts upholding masculinity more broadly. I’m deeply inspired by gender fluidity in fashion and consider queer and trans* voices essential in the discussion surrounding masculinity. However, with no deeper evaluation or alternative viewpoint, the exhibition’s hurried mentions of queerness manage to feel voyeuristic rather than inclusive. The final three looks being gowns was ironically the perfect summary of the exhibition: the show did not accurately represent the changing face of menswear, and the many nuances intertwined in this today.

Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 19 March – 6 November 2022. In partnership with Gucci, with support from American Express ®.

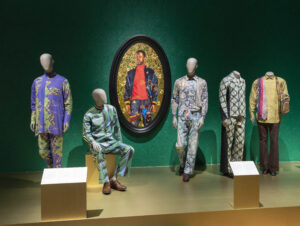

Featured Image: Installation view of Fashioning Masculinities at V&A, featuring Alessandro Michele for Gucci look worn by Harry Styles. Image courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum, London.