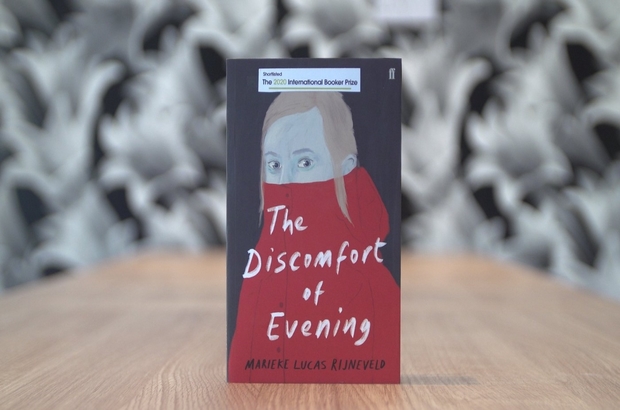

DAWID AKALA reviews this year’s International Booker Prize winner, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s remarkable yet disturbing debut novel, The Discomfort of Evening.

When 28-year-old poet Marieke Lucas Rijneveld tried their hand at prose and published a debut novel in their native Dutch in 2018, they could have hardly foreseen that just two years later it would catapult them onto the global literary stage. Celebrated for its ‘wild and violent beauty’, The Discomfort of Evening (translated by Michele Hutchinson) won the International Booker Prize this August, crowning Rijneveld as the youngest ever author to receive the prize and only the third Dutch author to be nominated.

In its distinct poetic style, the book tells the story of Jas, a ten-year old girl growing up in an emotionally inarticulate, devout Reformed Christian household on a dairy farm in rural Netherlands. The narrative opens with the death of one of Jas’ siblings in a skating accident, and from that point becomes a claustrophobic deepdive into her mind, tracking her and her family’s maladaptive reactions to their loss. As Jas observes her family’s inability to process grief, layering this inexplicable tragedy with her own child logic in the process, her perspective offers an imaginative take on rural life, religion and, most strikingly, how children cope with trauma in the face of emotional neglect.

Aside from the oft-cited, disturbing scenes – gut-wrenching passages that read like car crashes from which we can’t look away – a more subtle yet equally unforgettable feature of this novel is the confident originality of the narrative voice. Rijneveld’s similes are unusual and specific, clearly rooted in their background as a poet. We see lips ‘pursed shut, like mating slugs’, while locks of hair become ‘wilted pea pods’ and cheeks ‘bulge like two mozzarella balls on a white plate’. Jas, starved of parental comfort, wishes she could be embraced and rocked back and forth, ‘like a cumin cheese in a brine bath’. These images are clearly taken from nature and the pastoral, however given the novel’s subject matter and themes, the rural setting soon proves remote and isolating rather than idyllic.

In a similar vein, Rijneveld demonstrates their ability to distil complex emotions into singular, captivating images. It’s these memorable vignettes rather than action-packed sequences that anchor the story. The novel opens with one of these evocative images: ‘I was ten and stopped taking off my coat’. This red coat which Jas refuses to remove is the burning emblem of Jas’ complicated and oppressive introspection. Along with the pin she keeps stuck into her belly button and the squirming descriptions of her worsening constipation, this imagery heightens Jas’s inability to let go, to internalise, and to cope with her grief by dissociating into the safety of her imagination rather than showing emotion.

Rijneveld’s poetic approach is reflective of the novel’s pace. They aren’t concerned with a plot-driven story, and those looking for sudden twists and turns may be disappointed. However, at just 272 pages long, the book is rather on the shorter side, and Rijneveld’s command of language and metaphor proves strong enough to direct attention for this time. Arguably, they demonstrate that good writing is often about tension rather than action, and that no amount of time waiting for something to happen is too long provided that the behaviour is compelling.

Thus, rather than following point A to point B to point C, the novel’s structure appears as a sort of sheet-cake: layers of Jas’ attempts to make sense of the world after her brother Matthies’ death piling atop one another. Chapter by chapter Jas finds new obsessions, new inner worlds. Whether she’s on a mission to manifest her parents to be happy by encouraging two pet frogs to mate, or drawing up a secret plan with her sister to find a man from ‘the other side of the bridge’ who could rescue them, the story works by twisting on itself as a spiral rather than departing anywhere too far removed from where the narrative begins. Hence one of the most uncomfortable moments of the novel may be the realisation that these contrivances may never become fully resolved – and then, there is an unexpected, shocking ending. Even though it may come as a surprise, it’s seemingly the only conclusion that would make sense and therefore, while heartbreaking, still feels like a satisfying resolution. It’s probably fair to say that the initial narrative hook of Mathies’ death and the end of the novel are the two only big changes that happen in the story, with a chasm of dark rumination in between.

However, in being so preoccupied with the introspective, Rijneveld appears to neglect the external. The lack of a deeper exploration into how Jas’s family fit into modern Dutch society seems like a missed opportunity. Perhaps this is to accentuate the Mulder family’s sense of isolation from the world, most likely intentional on their part. However, a limited view of Jas’s school life – which in reality would most likely trigger some sort of social services involvement – may seem exaggerated and thus hurts the story’s plausibility. For instance, we never hear of the consequences for Jas’ brother, Obbe, whose coping mechanism manifests as violence. One of the book’s most harrowing scenes involves him playing a sadistic prank on one of Jas’ friends. Even though what Obbe does to her is exceptionally abhorrent and cruel, there is no reaction from the girl’s family.

Similarly, while Rijneveld’s poetic style and meandering structure lend themselves to reflecting a child’s dream-like perspective, they’re less convincing in belonging to a real-life ten-year-old with their advanced vocabulary and neurotic cognitions. Again, this means that the reader’s ability to suspend belief fluctuates throughout the novel.

In spite of these shortcomings, The Discomfort of Evening makes for a unique and visceral reading experience. In light of the Booker win, it’s great to see literature from less frequently translated languages being recognised, with Arabic Celestial Bodies winning last year and Polish Flights the year before that. What these books in translation have in common is that they place the Other – a foreign language – at the centre of universal, existential questions. In this case, we are presented with a burning study of how family dynamics directly mould a child’s developing mind. Jas admits: ‘All this time we’ve been so careful with Matthies that we don’t even talk about him, so that he can’t break into pieces inside our heads’. Rijneveld seems to argue how the risk of this ‘breaking into pieces’ may be worth it when the alternative is considered – the price to be paid for sweeping family trauma under the rug.

Featured Image Source: medium.com