KAITLIN FRITZ discusses Margy Kinmonth’s 2016 release, Revolution: New Art for a New World.

Margy Kinmonth’s Revolution: New Art for a New World illustrates the artistic triumphs and subsequent regression of creativity during the Russian Avant-Garde. The documentary brings together artists across different genres of painting, theatre, and design. Combining reenactment, interviews with descendants of the artists, and historical footage, Kinmonth weaves together the complex narrative of art in the Russian society.

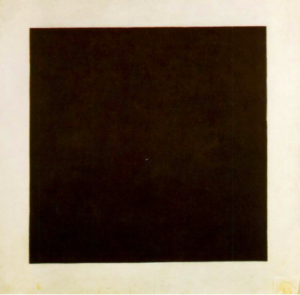

Set primarily in St. Petersburg and Moscow, Kinmonth examines the intersectionality of art and politics after the Russian Revolution of 1917. Vladimir Lenin, although partial to academic realism in the arts, recognized the power that the Avant-Garde movement could have for his new proletarian agenda. The film showcases how under his regimen, art and politics alike strived for innovation, utopian ideals, and Communist ideology. The vanguard of artists, most notably Malevich, Kandinsky, and Chagall, shattered the traditional artistic canon by introducing experimental techniques, radical trends, and newfound spirituality to the canvas. Their goal was to transcend into levels of thought and abstraction previously untouched. Kinmonth laces together both the physical artworks and cerebral philosophies of their creators to compile a thoroughly immersive analysis; for example, as she examines one of the most famous paintings of the time, Black Square, she also overlays Malevich’s own words explaining the importance of such a historic piece and its rebellious display in the corner of the room.

The film details the lives of the most famous and recognizable artists of the time, but Kinmonth also uncovers a trove of artwork unbeknownst to the Western art world. Hidden in museum racks, paintings from artists like Pavel Filonov are dusted off and showcased in great detail. Kinmonth’s fascinating discovery reveals to the audience Filonov’s unique style of figurative abstraction.

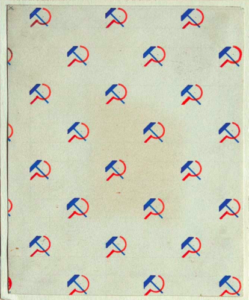

At the very height of their ingenuity, the avant-garde was abruptly halted at Lenin’s death. The documentary illustrates how under Stalin’s leadership there came a drastic shift; not only were artists’ works censored but they themselves were driven to become martyrs for their art. Many were killed or sent to the Gulag purely for their unruly creative spirit and determination to re-invent artistic practice. Kinmonth elegantly showcases this sudden change; when once experimental avant-garde artists were forced back into the frame of academic, figurative painting. Yet, there was still room for subversion… Kinmonth leads us down the interesting and unexpected avenues artists took in order to continue creating their Suprematist art. They found sanctity in the likes of ceramics and housewares.

Although Kinmonth reveals a spectrum of artistic media, one crucial characteristic of the avant-garde that underpins the movement is the multidisciplinary mentality of the artists. It is important to recognize that many of the artists who partook in the Russian avant-garde expanded created work across a range of mediums. The ideals of Suprematism and Constructivism were meant to expand and encompass all of Russian life. This was especially true for female artists of the time. Women, like Varvara Stepanova, Liubov Popova, and Olga Rozanova, created paintings, textile designs, and costumes, all of which embodied the Revolution.

From an art historical perspective, Kinmonth clearly articulates the major movements of the time — Suprematism and Constructivism — but fails to mention the distinctions between the artistic styles and the theory behind each movement. From a historical lens, Suprematism focused on the spirituality of non-objective painting and was founded by Malevich; whereas Constructivism, led by Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko, branched out from painting into sculpture, graphic design, and other mediums because this ideology highlighted the intersection between art and the modern industrial world.

Revolution: New Art for a New World features groundbreaking works and theories, and neatly summarises the rise and fall of the Revolution of Russian art. Kinmonth has created a film that peels back the layers of art and politics to allow a totally immersive experience of the experimental, creative, and destructive chaos that was the Avant-Garde.

Featured image Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition, 1915; image courtesy of oceansbridge.com